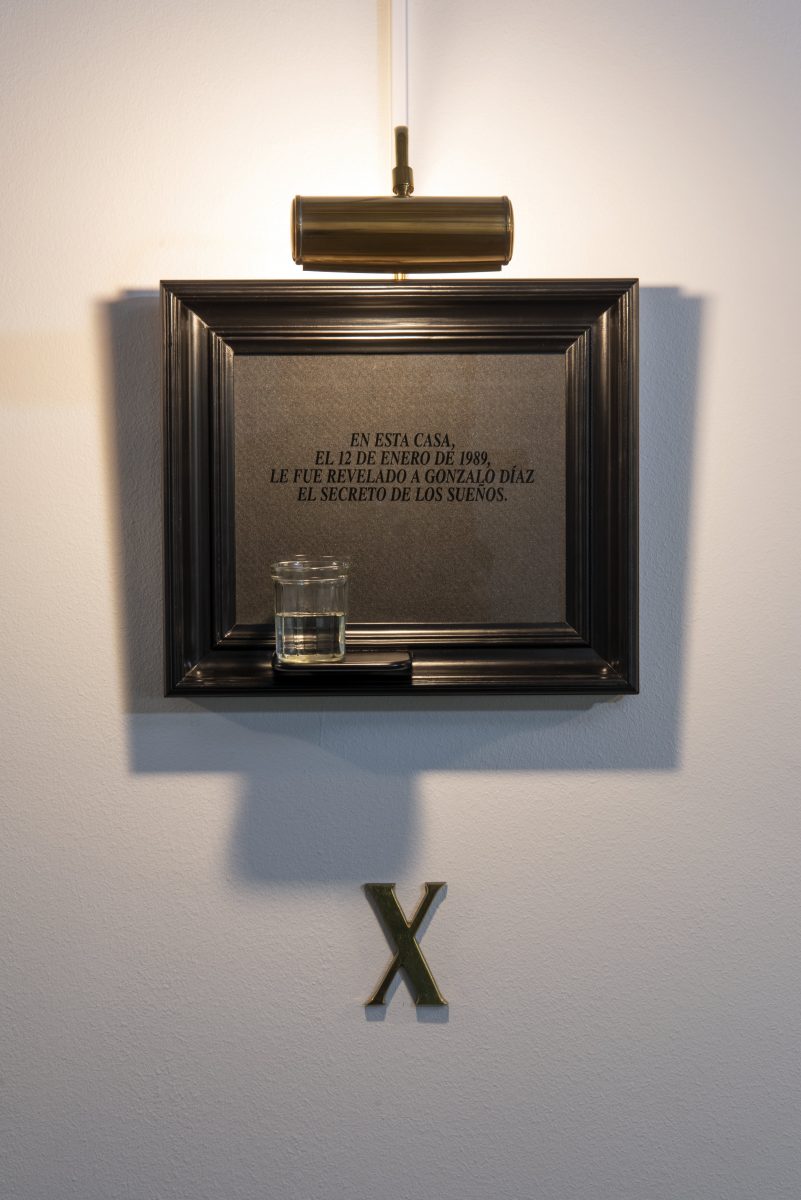

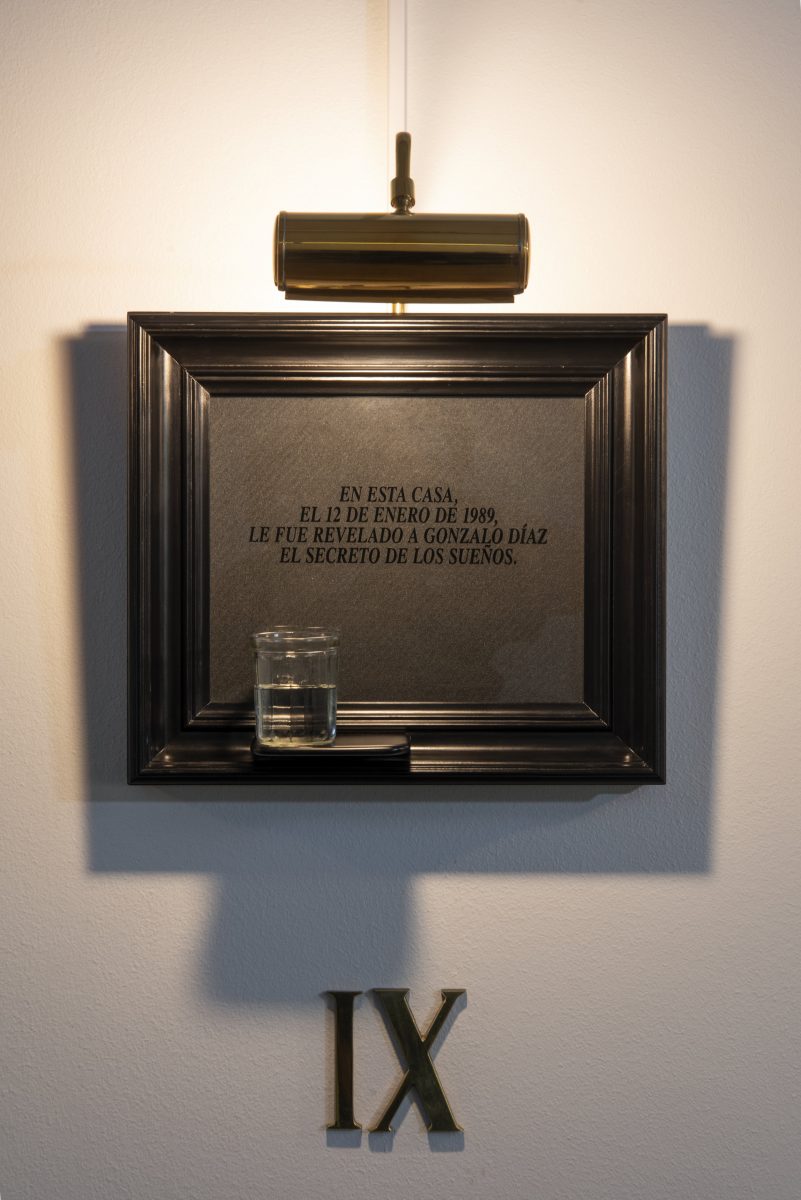

At the end of 1978, fifteen human remains were found in the furnaces of an abandoned cal mine in the Lonquén sector, southwest of Santiago. They were the bodies of fifteen local peasants who had been detained by police in October 1973, less than a month before the military coup. Almost exactly ten years later, on 12 January 1989, Gonzalo Díaz exhibited his installation ‘Lonquén’ for the first time at the Ojo de Buey gallery in Santiago: ‘Only after ten years of metabolic retention, of looking at what those half-point photographic jaws hide – architecture appropriate to the magnitude of a massacre – has it become possible for me to directly confront the Via Crucis of this terrifying matter,’ said the artist in the catalogue for that exhibition.

According to Pablo Oyarzún, the restraint Díaz refers to “is not simply due to willpower, discipline and conscious control, but has been forced by the blinding evidence of ruin, of that kind of funerary monument of “stone upon stone” (…) A restraint that is an admirable exercise in survival in art; in the survival of art, one might say, ‘in the midst of catastrophe.’