The return to pleasure

When I think of Gonzalo Díaz, the first images that come to mind are his incandescent installations in large spaces and his assembled objects, seemingly welded together like emblems of contemporary art. In my imagination, Gonzalo Díaz is the MacGyver of Chilean art, capable of solving anything with a paperclip and a piece of adhesive tape. Neon lights, words, tools, props, and mechanical arms have been the hallmark of his work since the 1980s—when he abandoned painting for concept, support for context, and the brush for urgency.

However, after forty years, he surprises us by expressing his desire to return to painting. He returns to it like a prodigal son, like someone going back to their childhood home, to the beginning of everything, to settle accounts or close cycles. This return to painting is a return to pleasure and also an opportunity to revisit a set of works created during a crucial period in his artistic career. For him, “painting is the mother tongue” and “a secret journey”1Gonzalo Díaz, Turungo. Diálogo & Archivo. Santiago: Il Posto y Metales pesados, 2023, 50, and this exhibition is a tribute to Gonzalo Díaz, the painter.

The painting lesson

His training as a painter began before he entered the School of Fine Arts at the University of Chile, when he took classes with Adolfo Couve in 1964. Once enrolled, he attended the workshop of Augusto Eguíluz. When Eguíluz passed away, Couve took over the painting course. And when Couve abandoned painting for literature, Díaz continued his teaching—from 1975 to the present day. I like to think that from Couve, he acquired an early awareness of the economy of means—something akin to what the young painter Augusto learns in La lección de pintura, Couve’s 1979 novella. In the book, the protagonist uses shoe polish instead of oil paints for flesh tones and toothpaste for zinc white.

The rule of three

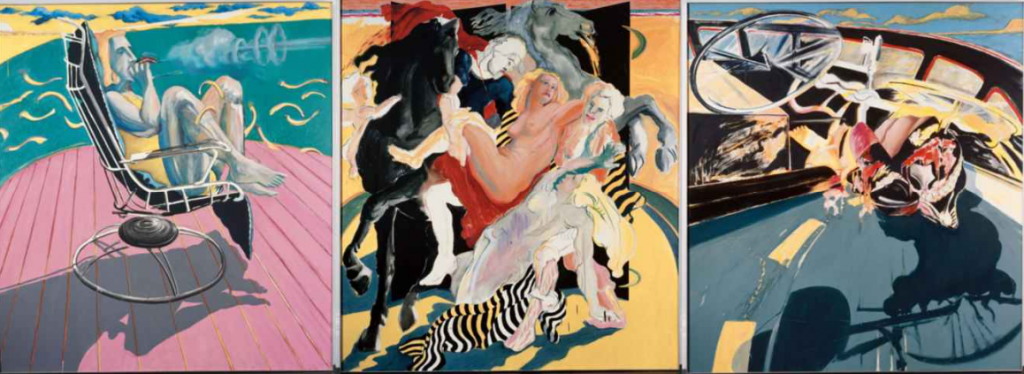

In Catholicism, three represents the Holy Trinity. In love, it is the figure of the love triangle. In navigation, it marks the location where ships disappear. In mathematics, solving for an unknown requires three values. For Gonzalo Díaz, three principles structure his painting. In 1980, alongside the exhibition of his large triptych Los Hijos de la Dicha o Introducción al Paisaje Chileno (“The Children of Bliss or Introduction to the Chilean Landscape”) at the National Museum of Fine Arts, the artist published a text written by him but signed by The Enthusiast. In this document, he defines a triad of concepts: crisis color, intended to manipulate and affect the viewer’s experience; the plumb line and level, which determine the rectangular and Cartesian format of his works; and the glass effect, referring to the smooth, flawless surfaces of a handmade reproduction devoid of painterly traces2Gonzalo Díaz, Tríptico de los hijos de la dicha o introducción al paisaje chileno. Santiago: self-edition, 1980. Archivo Il Posto. To this, one must add his tendency to produce works in series and to fragment them into parts—almost always three.

Fig. 1. Gonzalo Díaz, Los hijos de la fecha o introducción al paisaje chileno, 1979

Stendhal syndrome

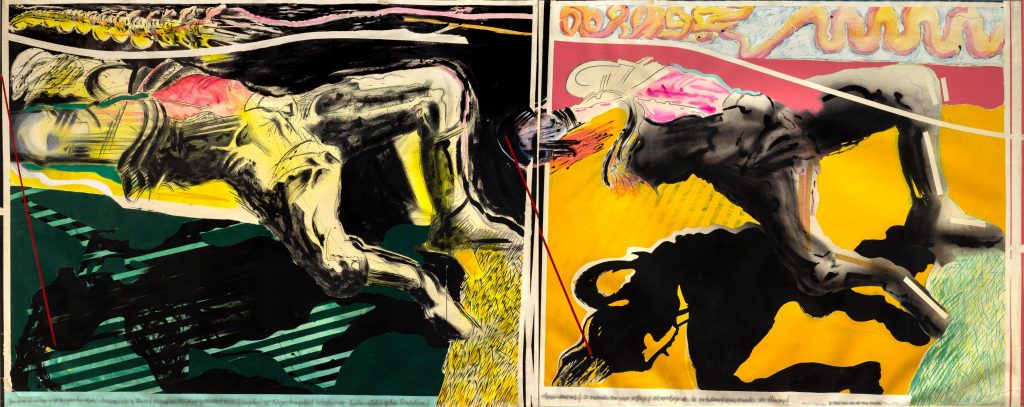

Gonzalo Díaz arrived in Florence in the winter of 1981. Once settled in his studio, he opened his suitcase and took out a series of images that would accompany him, pinned to the wall with thumbtacks, throughout that year. Among them were pages from Hoy magazine featuring photographs of the Lonquén ovens, where in 1978 the remains of individuals disappeared by the dictatorship were discovered, along with the image of a woman printed on the chrome-yellow packaging of Klenzo brand powdered detergent.

In Florence, he painted following the principles that had guided his previous works, subjecting figures to visceral deformation: dense shadows, alarming colors, pencil scratches, masking tape, and enamel gloss. But Florence was also where the Klenzo girl emerged as a devotional image, one that Díaz would turn into the patron saint of Chilean painting3Federico Galende, Filtraciones I. Conversaciones sobre arte en Chile. Santiago: Arcis y Cuarto propio, 2007, 156-184.

Since the French writer Stendhal traveled to Florence, the city has become an aesthetic experience akin to a mystical revelation through art. As visitors wander its streets, churches, and museums, they are overwhelmed by abundance, intoxicated by beauty, dazed, feeling strong palpitations in the heart, dizziness in the feet, and sweat in the hands, all symptoms of the “passionate emotions” awakened by “the fine arts.” Sensations akin to infatuation, which, in Díaz’s case, took the form of a woman-image: a blonde with blue eyes, a tight dress, a visible neckline, a white apron, a maid’s cap, a pearl necklace, crimson lips, and a flirtatious smile. This fascination gave rise to a sentimental story, a romance between the painter and his pop girl—an attraction sparked by the fact that she knew more than anyone about stains and working on smooth surfaces, leaving them clean and shiny, just the way Díaz liked.

Returning to Chile, the artist carried in his suitcase the Hoy magazine pages, the Klenzo package featuring the Madonna’s image, some new works, several cans of spray paint, and the official return of painting to the local scene.

Fig. 2. Gonzalo Díaz, Los hijos de la dicha, 1981

At the heart of Chilean painting

On July 17, 1982, Historia Sentimental de la Pintura Chilena (“Sentimental History of Chilean Painting”), an exhibition by Gonzalo Díaz, opened at Galería Sur. Here, the image of the Klenzo Madonna was reproduced hundreds of times—freehand or using stencils, painted or embroidered, on canvas or cotton paper. One room featured an Endless Tape, while another housed a series of 22 numbered prints. Among other objects and symbols illuminated by neon lights, four fabric panels hung with the silhouette of the Klenzo girl, intervened with stamped texts and embroidered with the help of artist Nury González. These pieces, suspended from door frames—like laundry hanging out to dry—remind me of a housewife’s cleaning apron, often a “tear cloth” or a dust rag, which Díaz used as a cloth to clean his brushes, leaving behind stains. Many stains. Stains that recompose Chilean painting, now as a history that revolves around the Madonna, with the purpose of elevating a popular icon to the heart of “the heart of Chilean Painting”4Phrase extracted from a work by Gonzalo Díaz.

Fig. 3. Gonzalo Díaz, Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena, 1982

The other Madonna

According to the artist himself, that European-looking blonde also represented art critic Nelly Richard, whose beauty was said to be capable of stopping traffic5Gonzalo Díaz, in: Federico Galende, Filtraciones I. Conversaciones sobre arte en Chile. Santiago: Arcis y Cuarto propio, 2007, 159. Richard dedicated issue #4 of La Separata, the cultural magazine she directed at the time, to Gonzalo Díaz’s exhibition. In her text titled “Reivindicación de la sentimentalidad como discurso”, she identified in Díaz a critical “revitalization” of painting—something opposed to what, a few years later, she would describe as “the return to pleasure” among depoliticized painter-artists6Nelly Richard, “Reivindicación de la sentimentalidad como discurso”, La Separata, n° 4, 1982, s/p. In her words, “against the self-repression of aesthetic enjoyment imposed by the political overdetermination of anti-dictatorship art, and against the severity of the analytical requirements of La Avanzada, the pleasure of color and the sensuality of the image reappear“7Nelly Richard, “La vuelta a lo placentero” (1986), Márgenes e instituciones. Arte en Chile desde 1973. Santiago: Metales pesados, 2014, 123.

Before putting the brush away

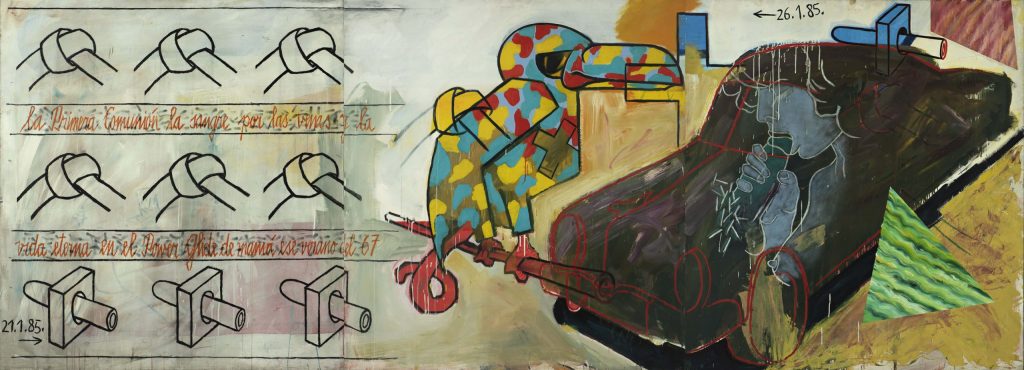

Díaz’s painting is structured around pleasure and sensuality. La Primera Comunión (“The First Communion”) (1985) is a large triptych. On the left panel, over graphic instructions for tying knots, the phrase can be read: “the first communion, blood through the veins, and eternal life in Mom’s Power Glide that summer of ’67.” In the center, a brightly colored bird makes us feel like uneasy witnesses. And on the right, against the dark backdrop of his mother’s Chevrolet, the memory of his first fellatio. This painting was created between January 21 and 26, 1985, and just two days later, it was exhibited in Frotándonosla, a show by Díaz and Jorge Tacla at Galería Visuala8For a deeper study of this work, see: Justo Pastor Mellado, “Texto auxiliar para la lectura del cuadro sin título presentado por G. Díaz en Galería Visuala”,Typed document, 1985.

Fig. 4. Gonzalo Díaz, La primera comunión, 1985

The dog’s loyalty

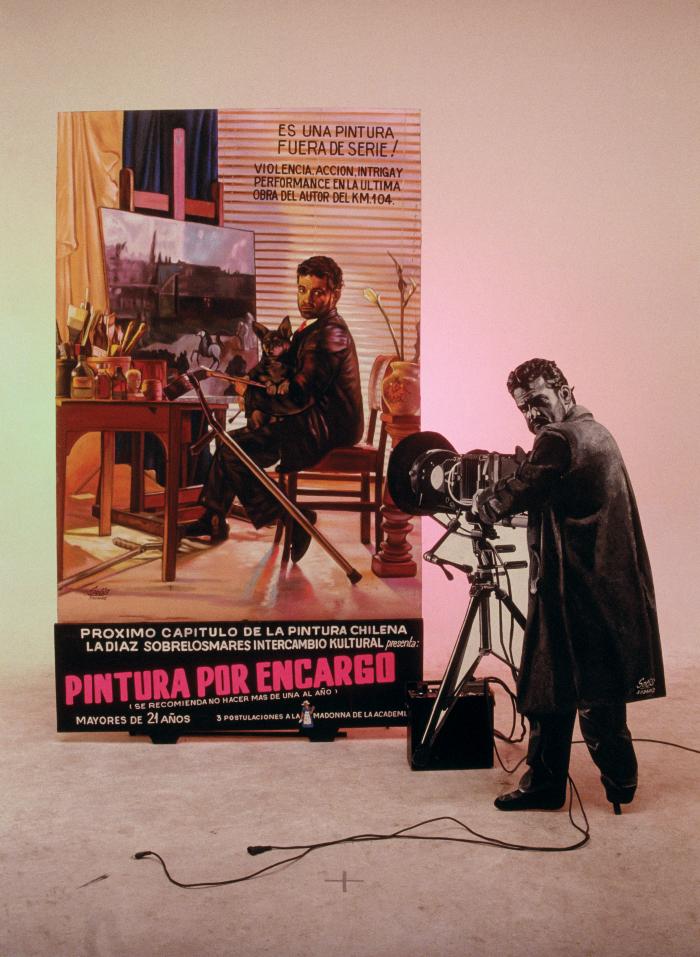

After the fellatio, the brush is put away, and 1985 ends with the exhibition of Pintura por Encargo (“Painting on Commission”)9Regarding this work, I recommend reading: Adriana Valdés, “Gonzalo Díaz : pintura por encargo”, in Composición de lugar: escritos sobre cultura. Santiago: Universitaria, 1996, 52-57 in the Fuera de Serie show at Galería Sur. This was his last work before abandoning painting—a piece that ironizes his role as a painter, even though he no longer paints. For this work, Díaz commissioned another artist —a movie poster painter named Solis— to paint his portrait based on a photograph. In the portrait, Gonzalo Díaz poses as a painter: seated before an easel, painting a work from his early period –Laguna Estigia (“Styx Lagoon”) from the Paraíso Perdido (“Paradise Lost”) series, 1976. Beside him, a table holds art materials and a crutch, while on his lap rests a small lapdog. Both the painter and the dog gaze outward, aware of their representation, their eyes heavy with sentiment. What stands out in this work is precisely the figure of the dog, historically used in art as a symbol of fidelity. In Díaz’s case, as he holds the dog with the same hand that holds the brush, it could represent his loyalty to painting —one he never truly abandoned.

Fig. 5. Gonzalo Díaz, Pintura por encargo, 1985