BEGINNINGS

The concept of “found images” (imágenes encontradas) was introduced by Eugenio Dittborn in 1976 and refers to images discovered and extracted by the author from outdated newspapers and magazines, interwoven throughout his works of art, where no figure is truly “original.” Broadly, these photographs are organized into two perspectives: on one hand, marginalized citizens, whether by ethnicity, occupation, or social class (criminals, pimps, indigenous people) and, on the other, athletes in action (swimmers, boxers, marathon runners) who have been forgotten over time. In the first group, the importance of their reappearance lies in the marginal and condemnatory social nature that motivated their photographic portrayal. In the second, the emphasis is on the gestures and expressions of effort and pain on the athletes’ faces at the moment of capture, alluding to the concept of “optical unconscious” coined by Walter Benjamin and theorized by Ronald Kay in relation to the artist’s work.

The writing that accompanies Eugenio Dittborn’s artistic and editorial works always includes a section where the author reflects on the nature of his art, declaring the iconographic sources that give rise to his figures and the significances that found images acquire on each surface:

El pintor debe sus trabajos a la adquisición periódica de revistas en desuso,

reliquias profanas en cuyas fotografías se sedimentaron los actos fallidos de la vida pública, roturas a través de las cuales se filtra, inconclusa, la actualidad (Dittborn, 1977, s.p.).

The texts presented in the following pages are the result of a research grant carried out at Il Posto Documentos during the autumn of 2024. The images, iconographic sources, and ideas noted here are the distillation of a long process of research, writing, cataloging, and dialogues with various people who crossed my research path over the past few years, regarding the artwork, documents, and found images of Eugenio Dittborn Santa Cruz, tirelessly transfigured in his art over the decades.

The body of text is organized into three sections, each broken down into brief notes that describe the artist’s creative processes while addressing the ideas surrounding my own solitary research journey. The bulk of this search and pursuit of Eugenio Dittborn has consisted of “re-encountering” the images used by the artist, printed in outdated newspapers and magazines and reproduced in a wide variety and quantity of artworks and art documents, which absorb and reveal them before our eyes.

I. ACTS OF PURSUIT

Quise hacer esta historia de personajes que han estado sumergidos,

pero que uno los ve en todas partes

Eugenio Dittborn, 1976

The first encounter

The first time my gaze was flooded by Eugenio Dittborn’s work was during the spring of 2018. In a task of registration, filing, and cataloging, the collector Paula del Sol and I had to move three gray Masonite panels (almost two and a half meters high) onto which eight transparent acrylic modules are affixed. Once we managed to measure the artwork’s ample dimensions and place it in a neutral space for photographic documentation, I clearly observed what lay beneath each transparency: above, a halftone photograph of a swimmer captured at the moment of breath over water, reproduced four times in silkscreen. Below, a drawing of a mummified child with fleshy lips and closed eyes, reproduced five times horizontally. The freeze-dried body contrasts with the wet and vigorous swimmer. Each figure stands out in electric blue, colored by strokes of Hi-Gloss paint and strips of pale absorbent cotton stretched beneath the acrylic.

As a result, these blued graphics unfolded before my eyes, impacting the future horizon and striking the body through their chromatic and volumetric effects. That moment sparked a future of long-term iconographic searches and pursuits, extending to other works by the author, where I repeatedly chased the sparks these electric figures shed in their inscriptions and color particles. Years later, I can still feel the blue of these figures vibrating among the waters as I embrace the gray walls – the same gray as the Masonite panels – that stretch across the interior of the artist’s studio. In this way, the work – titled A Whole Day of My Life and dated 1983 – extends infinitely into each of my searches within Eugenio Dittborn’s universe.

Fig. 1. Eugenio Dittborn, Un día entero de mi vida, 1983. Il Posto Collection.

Fig. 2. “Rumbo” supplement, from La Tercera de la Hora, May 25, 1982, p. 3

Archeological Remains

A month before the beginning of the summer of 1977, on the verge of opening his renowned exhibition “Final de Pista” at Galería Sur, Eugenio Dittborn described his own work in the local press: “I am an unearther, a digger. But not of old things. I am interested in the present and in recovering hidden pain” (Ercilla, 30-11-77). The act of plowing through these photographic captures —whose ruptures filter through the present, incomplete—sped up the flows and intuitions that guided my research on this artist, who is perceived as an archaeologist of a hidden past, an exhumator of images, and a chronicler of the present.

Fig. 3.Ercilla magazine, November 30, 1977. MNBA Press Archive.

In his essays, the Austrian art historian and philosopher Gottfried Boehm conceptualizes the study of a drawing as akin to excavation. Following the author, wherever images rest upon a double display—they show something and also show themselves—the observer perceives the oscillation of this dynamic in every area of the drawing, observing the dissimilar times condensed in this dual play between showing and being shown. From this standpoint, “the image comes out to meet us, it opens its eyes alongside ours” (2017, 188) and in fortunate cases, reveals the worlds behind its first visible layers.

After that first encounter with A Whole Day of My Life, I undertook the task of exploring different works by Eugenio Dittborn, seeking the images he once found and which now lie at the bottom of each intervened quadrant. This means traversing the stains, theories, and discourses poured onto each piece and once again unearthing the snapshots the artist once rescued. It means reviving the times that still pulse in the density of every blue shade.

Mirages of Illusion

The journey between found images and works of art moves freely between past and future. Photographs that once appeared in magazines that fell into disuse were rescued within an artwork and reactivated every time one observes them and perceives those material layers of temporal depth. Here, no figure is truly original; each one emerges from the ephemeral layer that brought it into view before the camera lens, or, in the words of Siegfried Kracauer, as “the residual component that history has discarded” (2006, 282).

In attempting to abstract these images to a state prior to their artistic transformation, two main issues arise: first, the need to rescue certain forms and minor, marginal details within the figures (Ginzburg, 1980) to find the images the artist once encountered—mouths, mustaches, hair, teeth, jewelry, captions, image outlines—and then, upon comparing the “re-encountered” photograph with its corresponding artwork, the question of what occurred in the interval separating each image’s before and after. Because when observing the figures transfigured within a work, we don’t just see the operations superimposed over their bodies and faces, but also the signs—feathers, fingerprints, oil stains, wool, stamps, cotton, and paper creases—that indicate something mysterious happened there, in the studio’s space, secret before the infinite gazes that will touch the universe residing there.

Forensic studies tell us that “In ‘before and after’ photos, the event is absent, and instead, transformation is captured… [in response to which] interpretation is called upon to fill the empty space between these two images with a narrative, which is also a place of imagined images and possible stories” (Weizman, 2014, 42). In this sense, throughout the search and reunion process, one can only speculate about the events occurring in the interval separating these images, about what Eugenio Dittborn’s hands, instruments, and stains summoned within each squared-off area. The illusory mirages that take place during my search processes are nothing more than fictions tinted in blue.

X-Rays

Examining signs and evidence, following the trace and outline of a figure, carefully attending to small and insignificant details, and trying to see the past in the present of a reproduced, transfigured, printed, and adhered image. With stealth, the trail of traces and signs pulses in one of the artist’s works titled Palmistry and Astrology (1981):

como quien, astrólogo, escruta, en la disposición conjugada de sus signos, el desenlace previsible de sus atracciones y repulsiones, el influjo benigno o pernicioso de las luces de los unos sobre los otros, la figura de sus órbitas, el estrépito de sus colapsos, la consecuencia de sus denigraciones, la hora de sus eclipses, la deriva de sus cuerpos constelados en el mapa celeste del cosmos interestelar ;

como quien, quiromántico, escruta, en la palma de la mano abierta que ellos conforman, la evidencia de sus destinos: recorrer milímetro a milímetro la huella fresca de sus pasiones fugaces, línea del corazón, el trazo intermitente de sus quimeras vanas, línea de la vida, el rastro tenue de sus mentes en blanco, línea de la cabeza, la pista borrada de sus carnes vivas, línea de la muerte;

When observing the collection of images gathered in this research, the work becomes analogous to that of an astrologer or palmist. The vision turns into the very desire to emit X-rays through one’s gaze, to unveil an invisible condensation and penetrate the layers of the world inscribed on a single plane of space and time. This same fantasy is what the women of northern Chile yearn for as they search the desert for the bones of their dead, the clothing of their mummies.

Fig. 4. Eugenio Dittborn, Nadador color, 1985. Il Posto Collection.

The discovery of X-rays was an optical and philosophical revolution that swept the world, offering a new sense of reality, “based not on outer surfaces, but on inner vibrations, close to consciousness itself,” as Beatriz Colomina writes in her studies on image technology and architecture (2021, 135). Applying this new contrast medium to Eugenio Dittborn’s work allows us to visualize a repository of once-invisible meanings within the works, for when we probe the context surrounding each found image in the pages of a magazine—with its paratextual elements, such as headlines, captions, publication dates, the journalistic text body, and the context of appearance where the image was first seen—events, characters, and allegories emerge that crystallize the author’s subjectivity beneath layers of paint, burned lubricant, feathers, and wool that touch upon the present.

Where modern architecture, influenced by the discovery of X-rays, sought to make matter transparent, this research seeks to achieve a similar translucence: the internal vibrations of an artist, seen through his found images as if they were X-rays of the bones awaiting beneath each work’s skin. Such a longing, of course, is and must remain unattainable. The writing we glimpse is instead the reflection of the palmist and astrologer who gazes at each surface’s blue (carrying the thunder of its collapses and projecting the evidence of its destinies). The assembly of bones and wrappings unfolds, fortunately, in our imagination.

II. CRIMINALS

El pintor debe sus trabajos al cuerpo de la persona humana deportado en estado fotogénico al espacio colectivo de la revista, consagración de su perpetuo desamparo

Eugenio Dittborn, 1977

Traces

During the first half of the 20th century, police detectives renewed their methods for searching for clues and collecting evidence at crime scenes. Modernity, its technological advances, and the search for absolute certainty were reflected in the production of images and evidentiary traces resulting from a series of empirical processes, which guided the principle of objectivity and, consequently, professionalized the figure of the detective before the public. Thus, the drive of monitoring institutions to ascertain what happened and who was guilty crossed its own threshold from the era of superstition (of the astrologer and palmist) to the era of reason, of the pragmatic and decisive police scientist, who seeks truth under concrete and above all visible evidence, such as a photograph. “Photography for the first time makes it possible to retain clearly and for a long time the traces of a man” (Benjamin, 63).

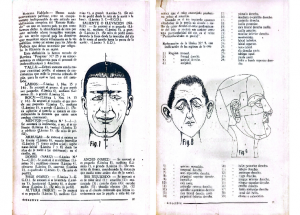

There is a historical relationship between the development of photography and its forensic use, exemplified in the work of the French physician and anthropologist Alphonse Bertillon, head of the Judicial Identity Department of the Paris police, who invented the police record card, defined as “a seemingly neutral and expressionless front and profile portrait,” essential for documenting and locating criminals on the run. Within this context, in January 1934, Detective magazine was founded by Chile’s then-named Police of Investigation, Identification, and Passports, aiming to “channel the needs for dissemination, instruction, and identity” and also to reach the general public through “light reading and information that would illustrate readers for their better defense against the professional criminal” (Rodríguez Morales, 2016, 480).

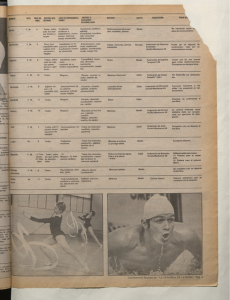

Detective published news and articles on the experiences of various police groups in other countries worldwide, with the goal of enriching and inspiring the work of the national institution. The contrast between the profile of the prophet and the scientist is highlighted in cases like the “Montessi case,” which occurred in Italy in 1953, during which a seer presented their insights in court. The headline reads, “Does telepathy help justice? ‘Seer’ intervened in the Montessi case: it’s not unusual in Vienna or Germany” (1953, 18), and the note underscores the important and effective role of divination in certain judicial cases, citing the example of Italian illusionist Enricco Ceccarelli and a session he conducted in Chile three years prior. According to the magazine, Ceccarelli hypnotized criminals at the Teatro Imperio in a special function dedicated to the Chilean police: “This function took place in 1950, and detectives gained valuable insights into the psychology of thieves and murderers.”

Fig. 5. Detective magazine, 1953. Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

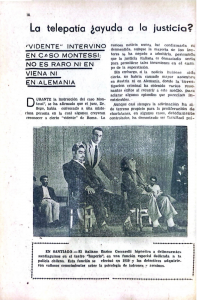

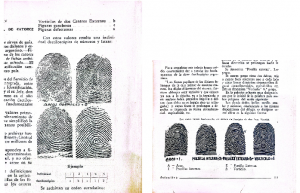

Despite this, over the years and the triumph of modernity, Detective published the latest criminal investigation procedures used in Chile and other cities of the Western world, totally opposed to the medium and based on standardized police identification formats: fingerprinting, document inspection, criminal records, palm prints, verbal portraits, police records, and the anthropometric system created by Bertillon.

Figs. 6 y 7.Detective magazine, 1955. Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

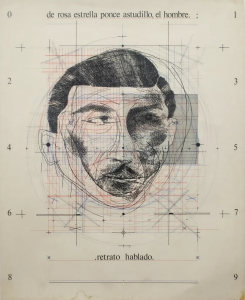

These identification formats, of course, are present in the works, documents, and iconographic imagery of Eugenio Dittborn, in the form of ink stains, spoken portraits, and police-style photographs, where men and women look at the camera, their image doubly arrested in history or, as Enrique Lihn put it, “The subject cast in the mold by the machine that stereotypes, produces, and identifies it” (1979) in reference to the criminals reproduced in the “Final de pista” exhibition. As one turns the pages of Detective and observes the inked thumbs on identification plates and standardized features in drawings, we see how the variety of faces rendered by Eugenio Dittborn over the decades vibrate in unison, where Dittborn does not imitate photography “but proceeds like the camera itself” (Lihn), using techniques that extend these subjects’ presence in the world into the present and the future of each blink.

Figs. 8 y 9.Detective magazine, 1955, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

Fig. 10. Eugenio Dittborn, Retrato hablado, 1975. Pedro Montes Collection.

Lights

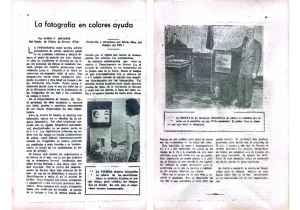

The trail of police photographs illuminated the courts in Denver, United States, when in the 1950s, the attributes of size, reproduction, and color capture became important in sentencing and identifying suspect faces. The police in that city acquired 35 mm cameras, compact and capable of being worn on a detective’s body. A reproduction system was also created in the courtroom that avoided overexposing the image with excess light, constructing screens attached to a projector where the negative was placed. Viewing each color photograph revealed details that had previously been invisible in black-and-white images, while expanding this type of image’s visibility more clearly and horizontally among courtroom attendees.

Figs. 11 y 12.Detective Magazine, 1955, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

The challenges of reproducing these color negatives, containing evidentiary images bathed in electric light within a judicial chamber, may very well mirror those an artist faces when mounting their work in an exhibition space. Fixation, reproduction, and access to image technologies marked the course of criminology while also impacting the paths of visual artists in Chile and worldwide.

Portraits

While photographic media made an impact in the eyes of the law, its captures were also felt in the visual arts. It’s unnecessary to dwell on the well-known, extensive discussions about the effects photography produced in relation to technical reproduction and pictorial practices during the first half of the 20th century. Nor is it essential to address here the influence of photography on Chilean art during the seventies and eighties, as that has already been extensively written about and theorized. Instead, it is worth colliding the trails that photography left simultaneously on artists and detectives, and from there, looking forward and backward at these arrested images.

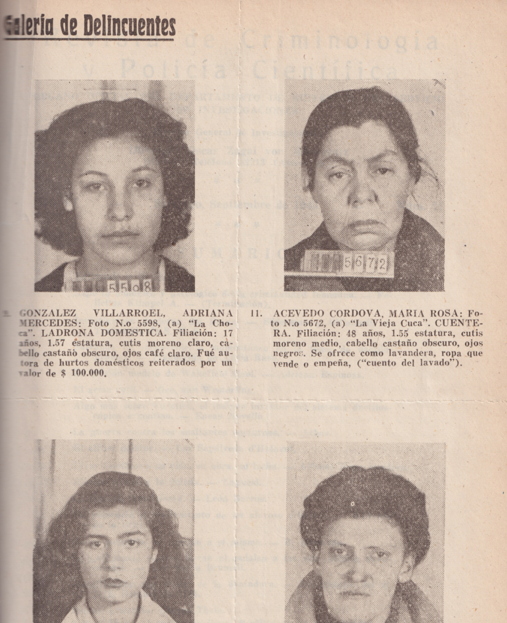

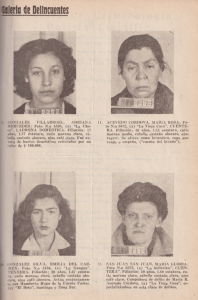

Gallery of Criminals

The criminal photographs in Eugenio Dittborn’s work are found in the “gallery of criminals” section of Detective magazine. Here we see the frontal capture, along with the name, photo number, alias, criminal specialty, age, height, skin color, hair, and eye color. Sometimes the crime location, other times the accomplices in the crime and the reward value. The images are printed towards the end of this magazine’s issues, on coated paper and arranged in straight, perforated grids, bordering the halftone photo of each criminal, allowing readers to tear out their printed faces with their hands. The idea was to carry the image of a bandit among curious gazes and anonymous pockets, allowing people to identify these men and women on the streets of Santiago, accuse them, and claim the offered reward.

Fig. 13.Detective magazine, 1945. Policía de Investigaciones Library.

The photographic image as evidentiary proof and identification tool modernized the police investigator’s work, while access to mechanical reproduction technologies allowed these photographs to be printed in mass runs in magazines and periodicals. In this way, the criminal portraits rescued by the artist are children of a time of photographic plenitude, where image access became attainable by the masses. This also had an effect a few decades later in the visual arts, where Eugenio Dittborn’s work consolidated through the use of this and other image reproduction technologies, like offset printing, photocopying, or fax.

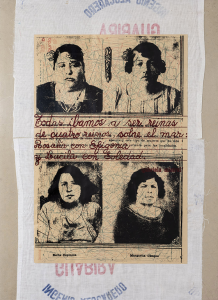

Posthumous Gazes

“Smudge would be a blurry photograph (not wounded by the gaze) though photography never seems to pick up the smudge that is a person, that biographed body,” wrote Guadalupe Santa Cruz (2011, 55). The body that stains, excretes, smudges—the spirit of a photographed body is boundless in the halting of an image. Photography lacks the capacity of X-rays to penetrate the surface down to the vibrations of the soul (if such a thing were truly possible). Instead, the photographs of female criminals found by Eugenio Dittborn—la camiona, la bailarina, la choca, la vieja cuca, la mancha, la Juana, la Juana chica, la regalona, la Petronila, and the legendary guagua—become characters that acquire a new script of posthumous life each time our gazes illuminate them through the artist’s ink. In the words of writer Silviano Santiago, “Observations about public persona(s) exist to transform into an illusory life script and join other characters in a dramatic and complex way, with the centrifugal force of artistic talent” (2022, 25). So what happened to these women, doubly arrested for crimes like domestic thefts, “money laundering cons,” and shoplifting accusations? What happens to them in our imagination each time we look at them?

Returning to these images found in Detective, highlighting the power of photographic identification that created them, and imagining the destinies consecrated in their perpetual abandonment is to see what Eugenio Dittborn saw, and to imagine the illusion his eyes cast over those figures of sharp, condemned women before the camera’s shutter. It means insisting on the smudge upon a biographed body and thereby making these and other phantoms visible, who, like restless fireflies, illuminate the spaces of their voids between the works and by air, grand and fluttering.

Fig. 14. Eugenio Dittborn, Reinas, 1979. Il Posto Collection.

III. WATERS

Hacia y desde las aguas todas, pedazos, trozos, indicios

de una memoria arada en su huidiza superficie.

Guadalupe Santa Cruz, 2011

Maritime Waters

When we look at the blue-hued scenes of summery and coastal locations, we see how in Eugenio Dittborn’s early works his characters lie comfortably among the sea waves and sand. Wearing swimsuits and goggles, some with pale skin and others sun-tanned, they look at us through cutting lines, fitting marks, and grids of acrylic paint, conveying a sense of well-being and tranquility that spreads across the linoca quadrants, from 1975 to the present.

The series Por un Solo Pez, reproduced in the book fugitiva (2005), is one of the few in which maritime waters appear calm and refreshing, contrasting with the other aquatic works featuring swimmers gasping for air, captured by the camera lens at the very moment they surface.

Streams

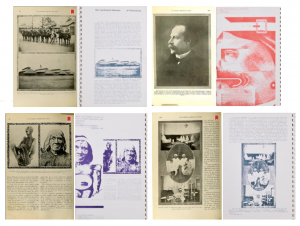

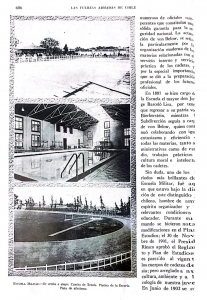

While flipping through the pages of Crítica Cultural magazine arranged on the walls of Il Posto Documentos by Ignacio Veraguas, I came across Eugenio Dittborn’s intervention in the second issue, published in November 1990, where the artist mentions two iconographic sources of his works: the books Pinte Ud! (1958) from S’Agaró, and Las fuerzas armadas de Chile. Álbum Histórico (1925). According to the text titled “FIGÚRENSE,” this latter military publication was given to him by the journalist Eduardo Olivares Palma in 1973, just before Olivares left for exile.

The impact was significant when, searching for the book online and scrolling through its 1,220 pages, I recognized certain images found by Eugenio Dittborn: photographs used in the delachilenapintura, historia series (1976) and reproduced in the catalog V.I.S.U.A.L. nelly richard rOnald kay dOs textOs sObre 9 dibujOs de dittbOrn (1976). Listed in order, these include three photographs taken in a hospital, reproduced by the artist in the mentioned catalog, the photograph used for the work El ñauca, epopeya; the photograph of Manuel Balmaceda used for the piece Don Capacho Condorcueca, Cachivache; the photograph of the stables of the Artillery School printed in the same catalog, and the photograph of a military pool filled with water and without submerged bodies, which took shape in the piece NADA, NADA. Although this last work appears in the exhibition catalog, its name is not listed among the total works enumerated in the handout distributed during the show. For this reason, and given that the catalog was produced after the exhibition opened, it is likely that NADA, NADA was included only in this printed format and not on the gallery walls.

Figs. 15, 16, 17 y 18. Eugenio Dittborn, V.I.S.U.A.L. nelly richard rOnald kay dOs textOs sObre 9 dibujOs de dittbOrn, 1976. Catalog of exhibition held at Galeria Época. Pedro Montes / D21 Collection.

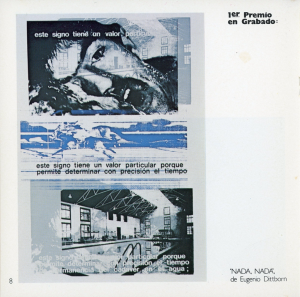

Still Waters

NADA, NADA is a work where the image of the military pool converges, its apparent tranquility interrupted by two other figures accompanying this photographed pool from 1925: a swimmer gasping for air and looking directly at the camera lens in the foreground, and a horse mounted by a rider in mid-gallop. The composition is arranged in layers and various shades of ink: above, the swimmer in dark colors, set against the image of the pool in lighter, brighter tones; in the center, the image of the horse; below, the initial part is repeated but inverted, with the pool darker than the swimmer. Over each of the three sections, a fragmented sentence completes towards the end:

Este signo tiene un valor particular porque permite determinar con precisión el tiempo

Este signo tiene un valor particular porque permite determinar con precisión el tiempo de permanencia del cadáver en el agua

The photograph of the horse in this work is the same that the artist reproduced a few years later in the publication Fallo fotográfico (1981), printed in silkscreen with bright blue ink on recycled cardboard, with a monochromatic interior of photocopies, where again and again Dittborn asked himself and those around him, “What is a photograph?” “A photograph is all that moisture, a photograph is the prison of an indelible memory, a photograph is a whole day of my life” (Dittborn, 1981, s.p.).

Fig. 19. Las Fuerzas Armadas de Chile, 1925.

Fig. 20. Catalog of the First Graphics National Salon, 1978. CEDOC.

Fig. 21. El Mercurio, October 15, 1978. Víctor Hugo Codocedo Archive, Rosa Lloret Collection.

In 1978, the work was presented at the Primer Salón Nacional de la Gráfica organized by the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. This piece won the artist first place in the engraving category and was noted by the local press for its “poster-like dimensions,” according to Ricardo Bindis in La Tercera (1978), and for its attributes of “aching drama… [combining] conceptual art and new figuration,” as commented by Waldemar Sommer in El Mercurio (1978). Over the years, Dittborn presented different versions of this composition, with variations in color combinations, typographical changes, and language of the printed phrases (in both English and Spanish). However, the structure of the photographs and the meaning of the words remain intact. Unlike other found images repeated in different works by the artist, this military pool record is confined solely to this series, thus keeping the Escuela Militar’s pool encapsulated within NADA, NADA.

It is worth noting that NADA, NADA was selected to be part of an international exhibition of Eugenio Dittborn at the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) in Buenos Aires in 1979. The selection included four different series classified by the artist’s formats and processes: cuadros de honor, impinturas, graficaciones, and serigrafías, with the work in question grouped in the latter. However, the text inscribed over the images caused concern for Jorge Glusberg, who directed the CAyC at the time, due to the possible connection of the text to the atmosphere of torture, repression, and forced disappearances that marked the dictatorships in Chile and Argentina. Today, we have the exhibition catalog, titled N.N.: aUTOPsIA (Rudimentary Theories for a Marginal Visuality) (1979), prepared by Dittborn and Ronald Kay and printed before the opening of this ultimately canceled event.

Despite this, NADA, NADA did travel abroad in October 1979 and, along with other works, was exhibited at La Trinchera gallery in Caracas, Venezuela. Thus, the waters of a military pool at the southernmost end of the hemisphere reached the Atlantic shores, on the eve of a period of economic and artistic prosperity in Venezuela’s cultural sphere, drifting along the waves and looking across the world.

Underground Waters

Underground waters are those hidden within the earth’s depths and have not been exposed to light

-Article 2, Chilean Water Code.

Swimmers repeatedly appear in Eugenio Dittborn’s works, just as the clauses of the Water Code and the quotes from Heraclitus of Ephesus moisten the surfaces of his work, along with the stains and aqueous substances that populate its background. At the beginning, I mentioned the case of A Whole Day of My Life, its dimensions, intensities, and impacts on gaze and body. This disparate structure, where a vital, moving figure above the waters opposes another still or deceased one in dryness, recurs throughout the artist’s repertoire over the years.

It is worth looking closely because there are no random elements in Eugenio Dittborn’s works, and behind every stroke, stain, word, image, and calligraphy, abyssal routes intertwine visible meanings. Thus, when observing these compositions and focusing on their contrasts, one questions a hidden principle, one that condenses the history of our local, recent world, as if the artist left a clue there, speaking without saying, waiting for our posthumous gazes to reveal the forces of histories, biographies, and upheavals he once crystallized, so as to bring those underground waters to light, quietly drenching and exhausting us. To look at these found sports figures and pause among the droplets is to take fresh breaths of air. To confront and compare the pages, photocopies, and silkscreens containing the same contrasting scheme: water and land. Movement and stillness. Stroke and suspension. Moisture and desert.

Lastly, let us ask some retrospective questions: Is it a coincidence that 1990, Chile’s first year of democratic transition, marked a decisive moment for revealing this final fraternal gesture by Eduardo Olivares Palma before he went into exile? What does this revelation under the word “FIGÚRENSE” signify at the start of this political transition period, amidst bodies, military pools, and concealed corpses in the water?

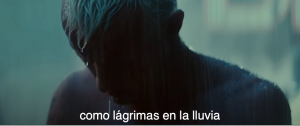

IV. LIKE TEARS IN THE RAIN

The back-and-forth paths traced on the preceding pages are the transcription of some drifts deployed during a long iconographic and detective journey around the works of Eugenio Dittborn. The passage of time, understood as the sum of lapses and spaces that permeate the artist’s work and the research process itself, allowed for a distillation of the openings and musings that unfold in the previous paragraphs and notes. It is worth mentioning that the projects e.dittborn 74/86 and las imágenes encontradas de eugenio dittborn were the foundational pillars for this process.

The exercise consisted of sifting through the misfiled images of the artist, discerning the paths of their journeys, rediscovering fragments outside time where our own existence slides through, returning to the stories of the forgotten that Eugenio Dittborn reclaimed, rescuing their faces through the fiction projected by our gaze as it rests upon a work of art. In the artist’s words, “To copy out the dead, retrace their tracks, follow the steps of their bare feet; move their remains, a bearable load of scraps, a cargo of dust; extend memory like a stain, understand memory as a memory spill” (1981).

The found figures transcend different periods in the artist’s work, from features, gestures, and bodies outlined in rapidograph grids, to photo-silkscreen inscriptions on airmail paintings, passing through stains and prints on stone cardboard or jute canvas. Thus, over the years, as media and inks vary, as signs and traces are added or subtracted on the surface, the essence of those once-rescued individuals remains intact within the works, spanning eternity.

The journey undertaken around these images raises two closing points:

- The depth and impact of the found images in Eugenio Dittborn’s work lie in the simplicity of the action that brings them to life, without encrypting what we see, but rather allowing these misplaced characters to resonate naturally before the eyes that frame them, releasing the oscillations of time and history.

- What truly happens in the hidden interval between the found image and the artwork are unreachable actions, veiled by the mystery and stealth that dwell within a work of art. In this case, captures of a smudge, spilled corpses, exhumed images, commonplaces, hidden blurs, blue-tinted stains in transit, in shadow, in dust, in years.

Amidst languor and melancholy, we coexist with the moments and characters glimpsed by the artist, surpassing the loss of their buried futures, destined to be scattered in fragments of earth, desert, and sea. Rescued from the vastness of the infinite, like tears in the rain.

Fig. 22. Still from the feature film Blade Runner, 1982.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Benjamin, Walter (1980) Poesía y Capitalismo. Iluminaciones II. Madrid: Taurus.

Boehm, Gottfried (2017) Cómo generan sentido las imágenes. El poder de mostrar. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas.

Colomina, Beatriz (2021) Arquitectura de Rayos X. Barcelona: Puente Ediciones.

Dittborn, Eugenio (1979) Estrategias y proyecciones de la plástica nacional sobre la década de los ochenta. Santiago: Autoedición.

Dittborn, Eugenio (1981) Un día entero de mi vida. Santiago: Autoedición.

Dittborn, E. (1981). Fallo fotográfico. Santiago: Autoedición.

Ginzburg, Carlo (1989) “Morelli, Freud y Sherlock Holmes: indicios y método científico”. En Eco, Umberto; Sebeok, Thomas. El signo de los tres. Barcelona: Lumen.

Kracauer, Siegfried (2006) Estética sin territorio. Murcia: Fundación Cajamurcia.

Lihn, Enrique (2008) Textos sobre arte. Santiago: Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales.

Rodríguez Morales, Teresita, “La revista Detective de la Policía de Investigación, Identificación y Pasaportes de Chile. Santiago 1934-1937” in Galeano, Diego y Luiz Bretas, Marcos (Coord) (2016) Policías escritores, delitos impresos. Revistas Policiales de América del Sur. La Plata: Diego Antonio Galeano.

Santa Cruz, Guadalupe (2023) Ojo líquido. Santiago: Bisturí.

Santiago, Silviano (2022) Grafías de vida. Buenos Aires: Malba Literatura.

Weizman, Eyal e Ines (2014). Before and After: Documenting the Architecture of Disaster. Moscú: Strelka Press.

Código de Aguas. Art 2. 1981 (Chile).

Press documents

Ercilla magazine, May 19, 1976.

Ercilla magazine, November 30, 1977.

El Mercurio, October 15, 1978.

La Tercera de la hora, October 15, 1978.

Exhibition catalogues

Dittborn, Eugenio. (1976) delachilenapintura,historia. Santiago: Galería Época. Source: Pedro Montes Collection / D21.

Dittborn, Eugenio. (1977) Final de pista. Santiago: V.I.S.U.A.L. / Galería Época.

Dittborn, Eugenio y Kay, Ronald. (1979) N.N.: aUTOPsIA. Santiago: V.I.S.U.A.L.

Galería La Trinchera. (1979) Sin título (Expo. en Caracas). Caracas.

Paroissien, Leon [Edt.] (1984) Fifth Biennale of Sydney. Private Symbol: Social Metaphor. Sydney. Source: Pedro Montes Collection / D21.

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (1978). Catálogo del Primer Salón Nacional de la Gráfica. Santiago: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

Sources of found images

Detective magazine, 1945.

“Rumbo” supplement in La Tercera de la Hora, May 25, 1982.

Silva Vildósola, Carlos (1928). Las Fuerzas Armadas de Chile – Álbum Histórico. Santiago: Empresa Editora “Atenas” Boyle y Pellegrini Ltda.