There is an image that remains in the way Jorge Tacla paints landscapes in destruction. Sometimes it may be perfectly hidden, but it refers in various ways to a decisive moment during his stay in the Atacama Desert in 1989, when he traveled to Chile with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship. Left to the solitude of his inner world, after days of walking and sitting to observe the driest place on Earth, it seemed evident that nothing changed in that desolate landscape: there was nothing but the wind, space, and the sun. Except for his papers, which were burning away, he found himself in a place seemingly impervious to time, apparently unaltered—until one day a military plane flew over his head at full speed, a low-altitude thunderstorm patrolling the border, Tacla recalls in a conversation with Joseph Ruzicka:

At that moment, my idea of space changed because I realized that all these things existed that I could not see. What seemed to be an empty space was, in fact, full of lines and directions, loaded with information. These are the traces of technology. You can’t touch or see the direction of these lines.

The scope of that image reverberates throughout the different works exhibited in Natural History of Destruction. The paintings and records gathered here showcase the impact of that awakening on the artist’s prominent career. Belonging to his iconic series—Sign of Abandonment, Hidden Identities, Anatomy of Dyslexia, and Rubble—these works make visible the different stages of an unceasing quest to represent space, not in its physical dimension but in its sense of transformation. Each, in its own way, implicitly contains the same guiding thread. In one of his notebooks, Elias Canetti writes, “The credibility of memory is obtained by that which we exclude from it.” How to represent the lines that converge in that space, the ongoing relational processes associated with that tragedy?

In On the Natural History of Destruction, German writer W.G. Sebald tries to understand “the way in which individual, collective, and cultural memory deal with experiences that go beyond the bearable.” In the first of the Zurich lectures on “Air War and Literature,” collected in the book that inspires this exhibition’s title, Sebald points to a sinister aspect of amnesia with an epigraph by Stanislaw Lem: “The trick of elimination is the defensive reflex of any expert.” In conversation with Jorge Tacla for this exhibition’s catalog, the artist illustrated the tragedy of total annihilation with the firepower of the air missiles that attacked Lebanon in 1996, which inspired his Rubble series.

Ruin is the state of memory. The only place we can hold onto is history. We walk on contemporary ruins, for which certain records and references must be kept.*

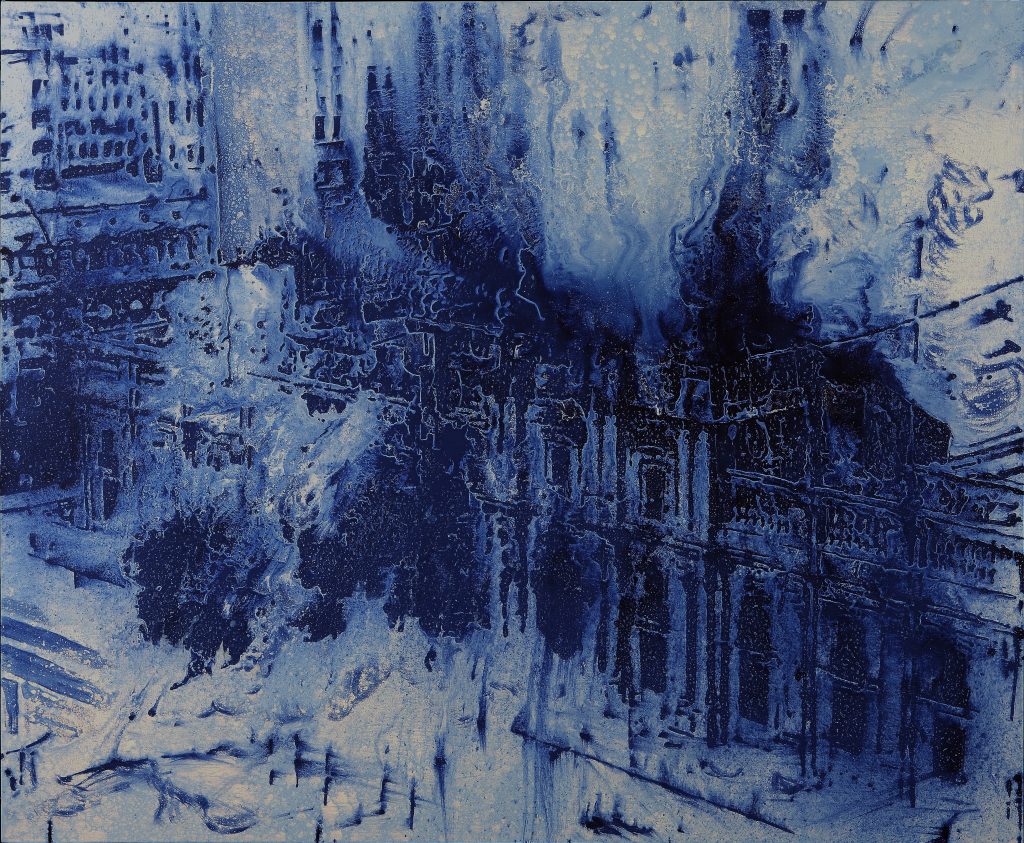

Fig. 1. Jorge Tacla, Rubble 19, 2010

The destruction caused by these air missiles, capable of making not only buildings disappear but also their rubble (“the record of ruin”), reclaims a strategy of historical domination through suppression, denial, and silencing. This extreme drive, also present in the violent image of the colonizing tabula rasa, as in book burnings or the forced disappearance of people, represents the most savage and devastating manifestation of the antagonism between memory and oblivion, making our history “a sequence of improbable images that distort and overlap reality, mixing and combining in the strangest ways,” as Arturo Uslar Pietri notes. The ruins we live with are not only the material debris and remnants of the past; they constitute, above all, testimony to the losses associated with that disappearance. Furthermore, they force us to deal with a series of conflicted leftovers, the immaterial rust of decaying political institutions, defeated ideological structures, and archaic biases that persist despite the accelerated degradation of the present.

I believe the ambition of power has been so deranged that it is making us witness destruction day by day. And in that destruction appears the internal biology, where human activity resides, which is invisible when the façade is intact.*

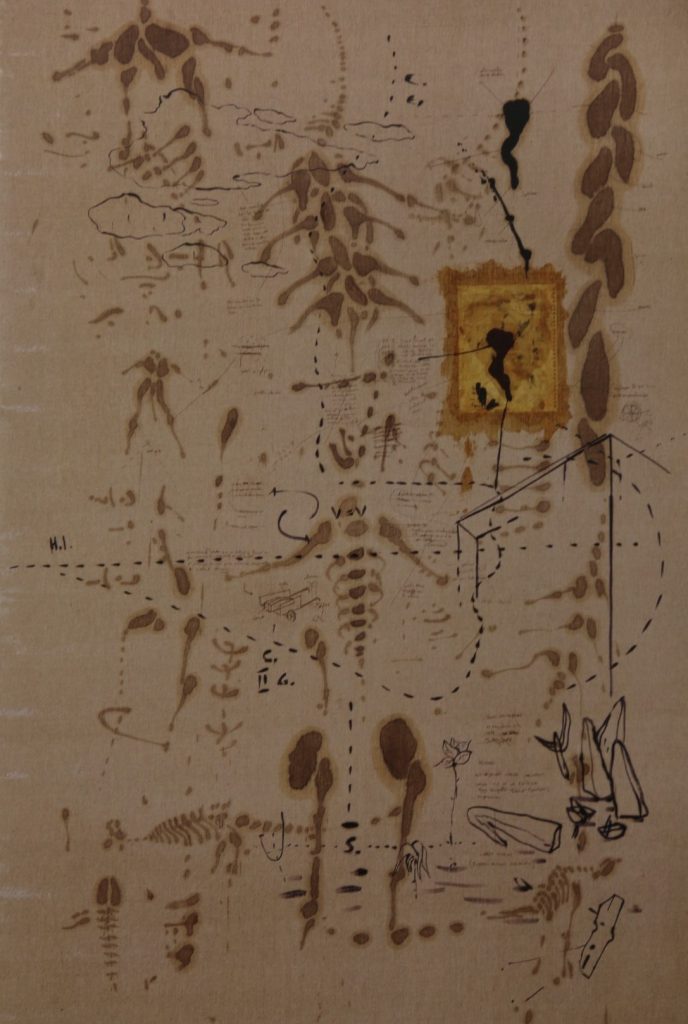

After the impact, the structure becomes permeable, revealing the complexity of its inner layers. Positioned from the perspective of a missile plane, Tacla pierces the façade to evoke the echoes and ghosts inhabiting the inner walls. We sense their presence in the forms. In both Biomechanism (1996) and Rubble 19 (2010), the dust is visible in the pigments.

Fig. 2. Jorge Tacla, Biomechanism 1996

In Paso por ti (2006), the artist captures the metallic remains of the Twin Towers, the surviving image of a Tower of Babel—which also evokes Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, also known as Monument to the Liberation of Humanity, which seems like an irony of history—as if in its melted foundations and pillars, its collapse had been prefigured.

One used to see the totems, magnificent, with their glass. Inside, there was an internal biology, and that is what remained in the end. Not that great power that is the façade of things. We walk over the place where humans conducted their activities.*

Fig. 3. Jorge Tacla, Paso por ti, 2006

In Tacla’s paintings, mind and matter blend over and over. The residues of these frictions form a repository of information he taps into with the rigor of a forensic archaeologist. “The earth’s surface and the products of the mind can disintegrate and disperse in specific regions of art,” says Robert Smithson. His reflections on landscape and industrial ruins are illuminating for understanding the perplexing shapes created by the relationships between space and the material properties Tacla meticulously works with in each piece. “Our mind and the earth are in a constant state of erosion. Mental rivers wear down abstract shores, brain waves undermine cliffs of thought, ideas decompose […] and conceptual crystallizations break into sandy deposits of reason,” Smithson writes in A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects (1968).

Tacla speaks of sites in Destruction. These are not monumental ruins or relics evocative of a present yet petrified memory, but rather the perpetual transformation of a moment after the explosion, the image that follows the breaking point that originated it: “The pictorial solution would make no sense if not for really seeking something of a particular depth.”*

The aerial image over the desert marks a trajectory in space, describing an extreme evasive maneuver. In Imaginary Horizon, Chandela (1990), the artist alludes to an emergency turn within a minimum turning radius that allows the pursued plane to become the pursuer. An effective maneuver in his Sign of Abandonment series, where the gesture towards what is lost no longer focuses on destruction, on rubble and its exposed biomechanics, but on preserving and conserving what remains, the intimacy of a latent space or the memory of an absence that slowly fades. “All old language is immediately compromised, and all language becomes old the moment it is repeated,” writes Roland Barthes, for whom the only way to escape the alienation of society was then by means of a forward escape.

It is not because of the destruction but because of the abandonment of that space. Contrary to what I do with other things, it is a manifestation of passion and love towards those institutions and those libraries, like Trinity College in Dublin, which have managed to preserve their books. If we think of the New York Public Library, the best books, the most valuable ones, are in the underground, where there is no access. They are kept safe so that people do not take them and damage them.*

Fig. 4. Jorge Tacla, Horizonte Imaginario, Chandela, 1990

One of capitalism’s problems is that it destroys the human possibilities it creates. People can develop, but in restricted and distorted ways. Inquiring into the psychology of destruction, Tacla has also judged a series of buildings that consolidate the architectural representation of power. Undermining their façades, exposing their interiors, “I took away their physical strength, weakened them.”* Exemplarily, in Hidden Identity 25, the concrete imprint of the territory projects onto the substance of memory. The iconic image of the bombed La Moneda—the bluish stain of burning fire, the contours of the canvas catching fire—seems inflamed by a subliminal geography of aerial landscapes, coastal edges, translucent layers where the territory appears viewed from the air in different perspectives and scales.

Fig. 5. Jorge Tacla, Identidad Oculta 25, 2013

“The aerial nature of sound, and by extension music, always implies some degree of insubstantiality and uncertainty, some potential for illusion or disappointment, a certain ambiguity between presence and absence, fullness and emptiness, enchantment and transgression,” writes David Took. There is a world of sound within silent things. In the desert, monotony was first broken by a noise. Looking at Jorge Tacla’s work, I think that his studies at the Santiago Conservatory and his background as a percussionist are essential to understanding the movements and oscillations that distort the surface of his paintings. At times, it’s as if the lines were reflected in a layer of water or recorded the vibration of strings that prevent the landscape from being fixed in perspective. Facing the silence of the unsaid, he seems always to be working in another intensity, secretly tuning into another silence, the silence of the unspeakable. In Jorge Tacla’s paintings, there is always a background noise, a certain wavelength that seems to resonate with that deafening storm, the accelerated sound of destruction.

From the most intimate to the most global, the relationship between victim and aggressor is a common thread in my work. The room of a family home, where a couple lives together; that room can also be a place of rubble. Family conflicts can become very violent and testify to how brutal intimacy can be.*

In most of these paintings, there are no bodies. If organic forms appear, they emerge from abstract lines, evoked by some indistinct outline of what remains. In his essay, Sebald tries to understand the fundamental reasons for an entire generation of German writers’ inability to describe and remember the experience of unprecedented annihilation. In the video Injury Report, only the ashes and the record of burned evidence—archives, clinical reports, personal notebooks—preserve the artist’s political past. “When the fissures between body and mind multiply to form an infinity of gaps, the studio begins to crumble and eventually collapses like the house of Usher,” observed Smithson. Every transition leaves a mark and suffers a loss in transit. Signs of life where no one is. Situated in the interstices of a disappearing world, Tacla manages to capture the echoes and vestiges of humanity that will survive.

*Conversation with Jorge Tacla, 08/18/2021