Something twin-like or, perhaps, fraternal inhabits Paz Errázuriz’s photography. Something that inscribes and exceeds the artist’s tendency to photograph two bodies simultaneously or to study the reflection of one on the polished surface of a mirror. Something that critically appeals to the binocular property of vision to dismantle its elusive wholeness. Something that connects the dual figure in her photography with another: the photographer and her off-screen presence. Something that allows the addition of one body to another without repairing its flaw. Something that disrupts duality due to its capacity to establish communication between the photographed body and another that materially lies outside the frame. There is something in Paz Errázuriz’s photographic work that acknowledges the anomaly of the copy, the failure of reproducibility in photography, the disparity of reflection, the inherent illness of the image. There is something in the complex duality of her photography that unsettles.

The Chilean artist Paz Errázuriz has been recognized and celebrated both inside and outside of Chile. Her photography has been interpreted as a politicization of those bodies rendered invisible or suspended by dictatorship and censorship, but also by the prophylactic gaze of visual modernity1The invisibility of these communities constitutes one of the tactics of disappearance applied to women artists. In her examination of the history of art and curatorial practices, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill has proposed the category of invisibility as a key figure to account for the absence of women in the influential canon of Chicano and Latin American art. Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, “The Invisibility of Latin American Women Artists: Problematizing Art Historical and Curatorial Practices”, in Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta, Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 (Los Angeles, Munich, Nueva York: Hammer Museum, DelMonico Books, Prestel, 2017), 21.. Paz’s subjects are elderly, transvestites, masked, racialized, battered, sick, insane, feminized, blind bodies. Errázuriz sneaks into the psychiatric hospital, the galleries and corridors adjacent to churches and temples, the brothel, the gym, the dance and circus floors, the indigenous villages, to propose to her models a contract of correspondence: a body-to-body encounter that becomes irresistible before the mechanical wink of Paz.

However, it is not an automatic exchange, a mere transaction, or a contract woven in anonymity or fleetingness. Because Paz Errázuriz does not steal, nor clings to the instantaneous. That is, she does not operate like other street photographers, artists who shoot aimlessly to surprise the passerby and generate the shock needed to fix the unknown, the ominous, or the unrepeatable—as happens with the American photographer Bruce Gilden, to name just one. The photographic contract that Paz establishes with those who pose for her is forged in a temporality alien to the gratification of immediacy, to the banal transaction, to the instantaneity that has defined contemporary photographic practices. Errázuriz slows down the speed that dominates visual immediacy: from the photo booth to the selfie, from the Polaroid to the smartphone. Her work advocates a temporality that does not conform to the productivist logic of 24/7 that Jonathan Crary defines as the late capitalism-driven overlap between the human subject and the global infrastructure of uninterrupted work and consumption2Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (Nueva York: Verso, 2013), 3, nor to the closed contract of professional photography. In a sense, her anachronistic temporality does not discard failure; on the contrary, it seems to incorporate it as a poetics, an essential starting point to be able to press the shutter.

It could be said that Paz Errázuriz’s most successful photography is that which never sees the light of day, which has been discarded, saved away, or simply never came to be. But this would depoliticize her decision to reveal, her courageous policy of showing these bodies, and might confuse her photography with a conceptual project. The artist proposes a contract in which the photographed gladly relinquish a trace of themselves to create something they intuit but ultimately cannot control or fully secure. In this sense, I want to insist that Paz Errázuriz’s photographic function is committed to the uncertainty of revealing the other, to the uncertain visual correspondence that requires a necessary leap into the void, and the probability—indeed, the near certainty—of its failure. Paz’s photography instills doubt about the otherness that, moreover, constitutes the enigma of all photography.

Critics who have reviewed Errázuriz’s work have emphasized how the artist’s gaze dismantles both the hierarchization of bodies and the tendency to redeem them—a bare gaze that neither judges nor protects, that neither pontificates nor concedes. It has been said that Errázuriz enables singularity without promoting the fetishizing violence of those who colonize a desire3Juan Pablo Sutherland, “Ensoñación y ficciones de identidad”, in Paz Errázuriz and Claudia Donoso, La manzana de Adán (Santiago: Fundación Ama, 2014), 21; that her photography eliminates the possibility of not seeing and introduces an artifact capable of looking beyond ethnographic documentation to penetrate the scientific gaze and take a leap into the politics of emotions4Andrea Giunta, Feminismo y arte latinoamericano: historias de artistas que emancipan el cuerpo (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI editores, 2018), 240; that her camera explodes both uniformed genders and the uniformity of gender, signs controlled by a repressive system5Nelly Richard. Introduction to Poéticas de la disidencia: Paz Errázuriz – Lotty Rosenfeld (Santiago: Barcelona Polígrafa DL, Catalogue of the Chilean pavilion of the 56 Esposizione internazionale d’arte La Biennale di Venezia, 2015), 46. All of this is true and even precise. However, less attention has been given to those operations that exceed the more immediate dimension of her politics, those that incorporate photographed bodies into the mechanics of the photographic device, those that directly challenge the device itself to open a gateway to emancipation. The politics of her images do not end with the act of introducing these marginalized and despised skins into the history of photography, nor with filling in the absence of the other’s gaze from the confines of the grand historiography of visual culture.

I understand Paz Errázuriz’s work as a profound discussion of the visual object and the imperative of visuality in difficult times; as an operation that, conceived upon the intrinsic duality of the photographic device—its binary encoding—ruthlessly attacks the visual programming that oppresses and sickens her protagonists. In this sense, rather than offering these bodies, marginalized politically and photographically, a privileged space—that of the photographic frame and therefore that of the artistic institution or a national identity or alterity—her images activate the politics of these sensibilities by denaturalizing the mechanisms and apparatuses that have historically captured them. Therein lies the radical nature of her mechanics, the politicized essence of her images.

I propose, then, to consider a photographic series by Paz Errázuriz where duplication becomes a practice that goes beyond the mere visibility of photographed bodies. In this regard, La manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple), in my view, represents a fundamental intervention for thinking about the image. It was published in 1990 as a photo book and was created in close collaboration with writer Claudia Donoso. From this perspective, this intervention is also marked by a dual challenge: the photographer’s invitation to a writer to establish a correspondence capable of penetrating the complexity of the other’s visual production6The issue of the couple in Paz Errázuriz’s work has been critically addressed. With special emphasis, the recurrent invitation that the photographer extends to other artists to investigate the image together has been discussed. Nelly Richard has pointed out how this invitation involves “the formation of pairs, teams, and associations among peers” that challenge the patriarchal myth of the author as a continuity between authorship and authority. Furthermore, in his reading of El infarto del alma, a collaboration between Paz Errázuriz and writer Diamela Eltit, Julio Ramos insists that this practice not only engages the law of names and authorship but also “the prohibition of ownership, the atomization of professionalized, institutional work.” According to Ramos, this production between two overflows and exceeds the instrumentality, economy, and solitude of the proper name. Nelly Richard, Introduction to Poéticas de la disidencia: Paz Errázuriz – Lotty Rosenfeld, 52. Julio Ramos, Sujeto al límite: ensayos de cultura literaria y visual (Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 2011), 158.[6]. This series also addresses the threat of illness—AIDS—as a figure that neither romanticizes nor celebrates precarious alterity but instead functions politically and photographically to expose the anomaly of copy culture, to fever and disturb the duplicated image as the only emancipatory possibility that photography offers for the most compromised alterities in history. As Hillel Schwartz postulates, the more we master techniques of duplication and practices of copying, the more confused become notions of the unique and the original7In his book, Schwartz wonders if it is not precisely in the likeness, in the construction of the similarity of the dual, where the more complex moral problems of our world and our times dissipate. Hillel Schwartz, The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likeness, Unreasonable Facsimiles (Ner York: Zone Books, 1996), 11[7]. It is in this figure of duality—anomalous and sick, feverish and frenzied, HIV-positive and psychotic—that Paz Errázuriz’s brilliant examination of photography and otherness, of photography as otherness, is framed. Here, the historical study of the enigmatic duplication in Paz’s photographic work is nurtured.

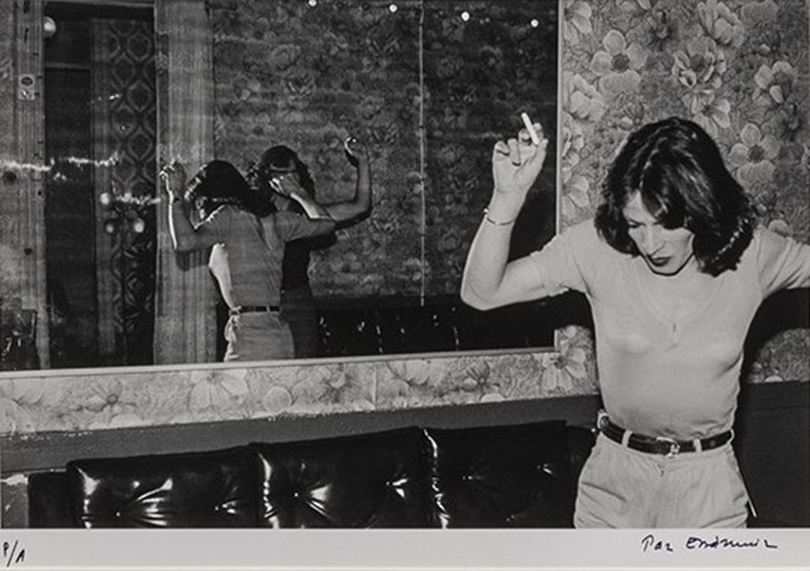

Fig. 1. Paz Errázuriz, La Manzana de Adán, 1981-1989

La manzana de Adán is grounded in an operation linked to failure. In the 1980s, Paz Errázuriz began photographing a group of prostitutes who worked at a venue in Santiago. However, shortly after she began, the women asked her never to show the images, never to make them public. Paz complied, and to this day, no one has seen those photographs taken on the suffocating nights of the dictatorship. At the same time, while photographing these women, Errázuriz noticed that their photographic reticence contrasted with that of other bodies which, by contrast, showed an excessive attraction to her camera8Paz Errázuriz and Claudia Donoso. La manzana de Adán (Santiago: Zona Editorial, 1990), 51.. It was then that Paz decided to photograph transvestites/prostitutes, as these stars of the night self-identified9I follow the way La manzana de Adán refers to these populations to account for the moment of production of the work. Likewise, I maintain the masculine gender to insist on the transvestite figure that dominates the sociability of the discourse, while understanding the limitations and inadequacy of its use. The artist then began to frequent the dark rooms of La Jaula in Talca and La Palmera in Santiago, where they operated and performed a complex revision of gender. In these precarious and, for some, sordid spaces, an acute reflection on the plastic possibilities of the body, gender emancipation, and the synthetic materiality of sex unfolds.

Fig. 2. Paz Errázuriz, “La Palmera”, from the series La Manzana de Adán, 1981-1989

With this series, first exhibited at the Australian Center for Photography in 1987, Errázuriz explores the trade of sex workers, staging their cosmetic transformation, the prosthetic construction of these corner-loving bodies. With her camera, the artist intervenes in the rooms where they produce a sophisticated iconographic review of the sexed body. For La manzana de Adán does not conceal the historic paraphernalia required to feminize a body, to place a sign on an epidermal surface to which it has not been assigned. From its title, La manzana de Adán references the use of a velvet ribbon—this prosthesis conceals the protrusion capable of revealing a body’s transvestism. Although, in a way, this ribbon symbolically amputates the ultimate sign of masculinity as a figure of origin, strangling it if you will, the photographic work does not attempt to erase the assignment of sex as a body marker. On the contrary, as its protagonists do, the photos display the mechanisms of transformation, making the body’s metamorphosis explicit. The photographer plays with optical illusion, with the insect-like ability of the transvestite scene—as Cuban writer Severo Sarduy’s theory of simulation argued10Severo Sarduy, Escrito sobre un cuerpo: ensayos de crítica (Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1969)—to provoke a commotion in the body, in gender, in sex, in its politics and aesthetics, in all its eroticism. Ultimately, this series proposes an absolute erasure of origin, a denaturalization of the originals of sex11I must remember that when Paz Errázuriz first exhibited La manzana de Adán, there had not yet appeared a book that would inscribe a path and an entire glossary on gender theory. I am referring to Judith Butler’s book, Gender Trouble, originally published in 1990, the same year La manzana de Adán was released as a photobook. I emphasize this to understand that the work of Errázuriz and Donoso manages to articulate something that was not yet fully acknowledged, even as a field, in gender and sexuality theory.

I want to explore how this idea is woven, how the discrediting of the nature of the body begins. As I previously suggested, the photographic narrative is rooted in duplication as both effect and trope. Mirrors, reflected and reproduced bodies, the connection between those who pose—all these figures seem to debate the intrinsic capacity of the photographic image to duplicate, the supposed reflective and mimetic condition of photography. In a certain sense, Paz Errázuriz’s images stroll through the watery history of photography, finding in the myth of Narcissus what could constitute the first photographic poetics in the history of the West. Paz harnesses the enigma of duplication and reflection, slowly noticing and making others notice the anomaly inscribed in every reflection.

Unlike other Chilean precedents, such as Bar Los siete espejos by Sergio Larraín (1963), Paz Errázuriz’s work establishes the asymmetry generated by the mirror image to thus disrupt and denaturalize, as I suggested, binary opposition. That is, Narcissus’s flaw is established when the reflected image reproduces as an anomaly. The desire of a body to produce its duplicate, the culture of copying that has dominated Western imagination, is interrupted by a leap in the image, by the failure of love that, seeking to reproduce an identical double, always becomes a desire for the other, which in turn detonates the flaw in the image, the error of the mirror. In a sense, Errázuriz developed in the 1980s a reflection that would later be explored by other photographers.

Paz’s photographs reveal that the reflection differs from the body that creates it, that every photograph denaturalizes, that the body of the other is always an anomaly, that we are not made in the image and likeness. Hence, the duality in the title: the other side of the series name references the biblical episode. La manzana de Adán alludes to the consolidation of sexual dimorphism, questioning the Edenic end of the founding couple to examine how the violence inscribed in the masculine-feminine binary opposition is installed and sealed. In this sense, the series leverages this “other” apple, unveiling and proposing a new beginning, not as an origin but as a starting point for establishing a new paradise in La Palmera, a novel beginning in La Jaula. Photographically, Paz Errázuriz begins with the double, with duality, to then explore the multiplication that constitutes every copy, the adulteration that ultimately makes the photographic camera possible in the age of infinite reproducibility.

And this is inscribed in the core of La manzana de Adán. Let’s not forget that the photographic series centers on a foundational story: the two children of Irene: Evelyn and Pilar. This pair, the origin of Paz’s project, rewrites duality, the twin or fraternal figure that organizes the composition of the series I’m discussing. It is around this sibling bond that the story is built, the series founded, and the photo book originally published by Zona Editorial in 1990. Even the photographic chronicle refers to the statue of the famous Roman she-wolf that nursed Romulus and Remus, located in front of the Talca train station. Evelyn and Pilar, Romulus and Remus, enable the uncertainties of gender when the photo book transcends the given name, historically tied to gender, and disrupts it: PiliPilar-Keko-Sergio and Evelyn-Eve-Leo-Leonardo Paredes Sierra. In a way, this operation is anticipated when Claudia Donoso writes: “Llegamos a Talca una noche de julio… sobre una columna de cemento supuestamente en ruina, una loba romana… Rómulo y Remo rodaron mamando en el terremoto de 1985, un año después de nuestra estadía en La Jaula, el prostíbulo de Maribel, que también se convirtió en escombros con el sismo”12Paz Errázuriz and Claudia Donoso, La manzana de Adán (Santiago: Zona Editorial, 1990), 19.

Fig. 3. Paz Errázuriz, “Pilar”, from the series La Manzana de Adán, 1981-1989

Fig. 4. Paz Errázuriz, “Evelyn”, from the series La Manzana de Adán, 1981-1989

Therefore, Paz Errázuriz installs duality rather than binarism in order to dismantle both dual and binary operations. As Rita Segato’s work emphasizes, binarism and dualism are not synonymous. To operationalize the difference, the Argentine anthropologist historicizes two intersecting figures of domination. Segato proposes the relationship between what she calls the world-village or pre-intrusion world and colonial modernity to demonstrate how high-intensity patriarchy, characteristic of the colonial model, intersects with low-intensity patriarchy, representative of pre-intervention structures. From this perspective, she highlights two distinct modalities: binarism and dualism, respectively. Her hypothesis suggests that the binary, always colonial nature of the State advances, intervenes, and dangerously disrupts the communal fabric of the dual world-village13Rita Segato, La guerra contra las mujeres (Madrid: Traficantes de sueños, 2016), 113.. Thus, due to its capacity to generate a low-intensity patriarchy, Paz utilizes duality in her composition, in the seemingly harmless trope of reflection, pairing, and the double, now as a figure prone to being broken and disconfigured to activate maximal duplication. That is, Errázuriz exploits the low-intensity patriarchy of duality to cause both the dual and the binary to explode through its deactivation.

The multiple reflections magnetizing these photographs manage to denaturalize both binarism and duality. They function like those rooms of infinite mirrors created by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama. The origin of the reflection disseminates into a web of reflections, mirrors reflecting each other to infinity, like a kaleidoscope that dissolves the origin of the world before our eyes. By causing the signs of Edenic binarism to vanish, man and woman are dethroned. The new couple reveals gender in pieces. Without resorting to these halls of infinite mirrors, Paz Errázuriz’s work stages the infinite reflection that, along the way, loses the original papers sealed at the very moment when Eve tempted Adam with the apple.

But let us remember that, in the biblical narrative, the apple carries a series of consequences that go beyond the expulsion from paradise, inaugurating nakedness, pain, illness, and death. Suddenly, the apple makes the first couple prone to illness and death, turning them mortal. The criticism of La manzana de Adán has focused on the symbolic reduction of these bodies in the face of the hegemony of heteropatriarchy and the moral censorship of the dictatorship. However, I want to note that the series also incorporates, albeit indirectly, another lethal figure for the inhabitants of these surfaces. Although Claudia Donoso’s chronicle accompanying Paz’s photos indicates that none of them feared AIDS14Paz Errázuriz and Claudia Donoso, La manzana de Adán (Santiago: Zona Editorial, 1990), 41, the epidemic envelops these bodies, threatening them with death. The plague is evident in the state of exception in which their choreographies are staged.

It is striking that the most provocative Chilean narrative, and perhaps the most influential written about AIDS in Latin America, Loco afán: crónica del sidario by Pedro Lemebel, uses photography to propose a temporal connection and even a pact between political violence and epidemic. In other words, Lemebel seems to find or, if you will, invent his new history of AIDS in the materiality of a photograph. After describing a final travesty party that occurred in the last year of the Unidad Popular, the chronicle notices a photograph that has survived the catastrophe:

De esta fiesta sólo existe una foto, un cartón deslavado donde reaparecen los rostros colizas lejanamente expuestos a la mirada presente. La foto no es buena, pero salta a la vista la militancia sexual del grupo que la compone. Enmarcados en la distancia, sus bocas son risas extinguidas, ecos de gestos congelados por el flash del último brindis. Frases, dichos, muecas y conchazos cuelgan del labio a punto de caer, a punto de soltar la ironía en el veneno de sus besos. La foto no es buena, está movida, pero la bruma del desenfoque aleja para siempre la estabilidad del recuerdo. La foto es borrosa, quizá porque el tul estropeado del sida entela la doble desaparición de casi todas las locas15Pedro Lemebel, Loco afán: crónicas de sidario (Madrid: Anagrama, 2000), 19.

The blurriness of the photo and, as this first chronicle of Loco afán later narrates, the moldy mark of the paper, detonates in the very photographic material the relationship between dictatorship and AIDS, the spectral connection between the political corpse and the corpse of the epidemic. However, the most interesting aspect of this first chronicle of Loco afán lies in locating such an intersection materially; that is, pinpointing it in the very materiality of the photo to then notice a singular disappearance, a single corpse. Furthermore, the discoloration of the photograph makes it indistinguishable whether the photo was originally taken in black and white or in color—this also creates a bridge between the two committed decades: the seventies, of the coup, and the eighties, of AIDS—once again revealing the punctum, the element that gives meaning to both cessations of the body:

Es difícil descifrar el cromatismo, imaginar colores en las camisas goteadas por la escarcha del invierno pobre. Solamente el aura de humedad amarilla es el único color que aviva la foto. Solamente una mancha mohosa enciende el papel, lo diluvia en la mancha sepia que le cruza el pecho a la Palma. La atraviesa, clavándola como a un insecto en el mariposario del sida popular16Pedro Lemebel, Loco afán: crónicas de sidario, 20.

The needle perpetrates the painful communication between both events, both exterminations17Javier Guerrero. “Las metástasis de la mariposa: Pedro Lemebel y el archivo analfabeto”, Cuadernos de Literatura 23, 46 (2019), 129. It simultaneously pierces the body and the photo, creating an opening like a communicating vessel. In some way, the photographic material tends to inscribe in the moldy, sick matter of the image the emancipation of the photograph itself.

This hole is also present in Errázuriz’s work, only that Paz’s photography accounts for this double disappearance in the very intersection of both temporalities: that of AIDS and that of the dictatorship. The photographer notices how both nest at the same time in a single epochal matter.

The epidemic constitutes the viral weapon of extermination. The disease hovers over Errázuriz’s photography because it represents the most direct threat to these sensibilities. The disease then activates as a necropolitical figure. However, in a certain sense, despite its binary condition, the photograph manages to fix an image that generates a survival, a life capable of extending beyond death. Susan Sontag has discussed the relationship between photography and death, as well as the metaphors of illness and AIDS. La manzana de Adán also functions as a grave, as a cemetery for all those bodies that perhaps were not mourned, that possibly were never claimed, or could only be wept for clandestinely. The disappearance of many of them was not due to the brutality of the dictatorship but to the system’s pact with the virus. Like the faded photo rescued by Lemebel, the black-and-white photographs of Paz Errázuriz capture the enjoyment of their material fullness or, as I mentioned before, the last year of their insect-like fantasy. However, this grave is not solely due to the urgency of fixing their disfigured or threatened corporealities and proposing the photograph as a shroud of light and shadows; but mainly due to its paradoxical ability to contradict the black and white of photographic binarism18In a private interview with Paz Errázuriz that I conducted in Santiago, Chile, in July 2019, the photographer confirmed to me that one of the reasons for her highly celebrated use of black and white was linked to dictatorial censorship. In other words, black and white photography allowed her to have control over her work, as the enlargement and development of the photographs were handled solely by her; whereas color photography required equipment that she did not control. Paz Errázuriz also recounted that once, during the dictatorship, after sending some color negatives to be developed, she received the original images obscured.. Paz Errázuriz’s La manzana de Adán manages to capture the bodies swept away by the viral operations of globalization, by the dreams of extermination that make them a target of war.

THE CONTRACT OF PAZ

Seeing Paz Errázuriz in action is quite an event. Understanding the counterpoint produced between her swift movements and the contract of her photography required an adjustment on my part. I remember that one of the first times I met with the artist in her studio, I found it difficult to keep up with the speed of her body; I was impressed by how quickly she moved from one place to another. I also recall when she invited me to see a work she had exhibited. It was the series Ceguera, which at the time had not “seen the light,” a piece displayed in a side marquee, lost in a gallery in downtown Santiago. It was not an art gallery but rather a somewhat deserted commercial hallway, where two of her photos were showcased in the display windows—two portraits of blind individuals that paradoxically framed an optician’s shop, that is, a place selling glasses and instruments to improve vision. These portraits of the blind, exhibited binoculary, symmetrically, challenge the dichotomy of vision/blindness. Again, her work disrupts the optical contract of photography.

My discussion of the duality in Paz Errázuriz’s photography does not aim to establish a formalist revision of her work. Or rather, I should say that my reflection on form is due to the fact that it synthesizes the figure from which the photographer generates the politicization of her work. Once again, it is not enough to reiterate Paz’s decision to make visible these denied communities, deprived of representation. Her operation is more complex and interesting. Eduardo Cadava has argued that for Siegfried Kracauer, the end of photography does not lie in reproducing a given object, but rather in its capacity to separate it from itself; that is, “what makes photography photography” does not rest in its ability to present what it can capture, but in its power of interruption19Eduardo Cadava, Trazos de luz: tesis sobre la fotografía de la historia (Santiago: Palinodia, 2014), 39.. Paz Errázuriz’s photography systematically interrupts the binarism inscribed in the device itself and in the old ethical pact of the photographed body as plunder, to open a new contract—a framework that witnesses the centers of love and body, the reasons why both the photographer and the viewers like us annex these other lives. There lies a fundamental figure in the work of this dazzling artist, a mechanism hidden in the ethical and aesthetic surface of her photos.

I also want to insist that these communities do not seek photographic vindication; they do not cry out for a rectification of history. They ask for nothing. When Paz shows them the photographs she has taken of the models from La manzana de Adán, they are disappointed. They expected Paz to explode color in her photographs20The inclusion of color photographs in the new edition of La manzana de Adán, published in 2014 by the Ama Foundation, can be understood as an offering, a tribute that seeks to mend a disappointment with color—a tribute of love.. The black and white, a convention that paradoxically legitimizes these groups in the history of author photography, seems insufficient to them21In a sharp reflection on photography and violence, Gabriela Nouzeilles recalls that the decision of American artist Susan Meiselas to photograph the Sandinista Revolution of 1979 in color sparked a broad controversy, in which she was even accused of war tourism in the Third World or of aestheticizing the tragedy of a country. Gabriela Nouzeilles, “Theater of Pain: Violence and Photography” PMLA 131.3 (2016), 714-715.. With this, I want to assert that Paz’s contract does not constitute a contract of redemption, nor, as I said, does it propose an automatic vindication of communities that have not asked to empower themselves photographically. What this contract does produce is a thorough revision of photographic models, the limits of their capture, and the dual and binary condition of the device.

To conclude, in this text, I have utilized the notion of a contract with her, in addition to unfolding my technology and understanding of photography and visuality as articulations that go beyond what frames the photographic frame or image, invoking the discussion articulated by Ariella Azoulay in her book The Civil Contract of Photography. The Israeli critic proposes a new ontological-political approach to photography based on the reexamination of the contract established between the gaze and the photography of Palestinian bodies, deprived of citizenship in their condition as victims of the conflict. The contract, then, accounts for their subjection to sovereign domination. Azoulay’s hypothesis is that if the image produces an unintentional effect that brings together its various participants—photographers, photographed bodies, viewers, and the device—all under the domination of the sovereign State, it may still have the possibility of suspending the gesture of power that dominates their relationships22“The civil contract of photography assumes that, at least in principle, the governed possess a certain power to suspend the gesture of the sovereign power seeking to totally dominate the relations between us, dividing us as governed into citizens and noncitizens thus making disappear the violation of our citizenship”. Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (Nueva York: Zone Books, 2008), 21. [Translation by Branden Wayne Joseph]. The context surrounding Azoulay’s problem, the occupation of Palestine and the second Intifada, differs from Errázuriz’s work, but it is based on the binary figure that inscribes citizenship. The civil contract of photography constitutes an alteration and interruption of the photographic model that finds in the reordering of the practice of observing suffering the key to a new encounter.

Paz Errázuriz occupies the dual model of photography, pausing at the binocular condition of the photographic image, in the reproducibility of the photo, to weave a contract in which the only correspondence is the possibility of besieging and, therefore, reprogramming the historical, mechanical, and now electronic figures of the photographic device. Indeed, her work interrupts the duality with which photography has been conceived and displayed. For instance, the historical and influential 1978 MoMA exhibition Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960, curated by John Szarkowski, framed photographic understanding in a duality: that of the mirror, capable of reflecting the portrait of its author, and that of the window, through which the world can be better seen23John Szarkowski, Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960 (Nueva York; Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 25..

La manzana de Adán offers a theorization about the image in difficult times that differs from the institutional dualism and binarism of photography by probing into the interruption perpetrated by those who will never again be anonymous or lack a grave.

Because, ultimately, now all these bodies rest in Paz.