1. Desire for magazine

The Revista de Crítica Cultural (RCC) was a journal that featured discussions, debates and conversations on aesthetics, art, philosophy and politics in Chile and the continent. It had a total of 36 issues in a continuous format of 24 x 35 centimeters. The first issue dates from May 1990, while the last one was printed in December 2007. According to Nelly Richard, cultural critic and director of the magazine, the discontinuation of the journal was due to the depletion of a “desire for a magazine”, an expression taken up by the synchronic closing of Punto de vista (1978-2008), another journal directed by Argentine critic Beatriz Sarlo1Nelly Richard, Introduction to Debates críticos en América Latina. 36 números de la Revista de Crítica Cultural (1990-2008). Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio / ARCIS, 2008.. Both publications emerged from a critical impulse in contexts of dictatorial oppression or its prolongation during the period of democratic transition, also known as post-dictatorship. They are desires, therefore, linked by national proximity and by a historical situation.

If the end of the Revista de Crítica Cultural was caused by the depletion of a desire, then it was a desire that sustained the journal. A critical and theoretical desire: a thirst for a magazine. I say thirst because this critical desire has the peculiar form of an insistence. I say thirst, also, because instead of attending to the necessary nature of a disembodied thought, I seek to penetrate the fibers of its needs. By reviewing the RCC as a whole and as an editorial project, we unfold the history of a critical will and the story of the realization of that desire. And if we are dealing with a desire, if this is the approach with which we approach the journal’s issues, then we are compelled to adopt a particular practice of the history of ideas. Whoever wants to read the RCC has no choice but to attend to a desire, as a peeping tom or intellectual voyeur, as an observer of the critical imagination of preceding years. A curious way of attending to the theoretical exercise, covered with affections, full of sensitivities.

This perspective certainly allows us to approach the Archive without relegating it to the silence of records and files or confining it to a recondite past. The following should not be confused with a nostalgic view of a past that has not been lived: returning to the RCC does not compel us to mourn, but to examine a moment in the history of thought whose physical testimony requires us to pay attention to its management. Desire is, as it is said -or as the Lacanian formula says-, desire of the other. Desire for a magazine would be, perhaps, an intellectual desire still to be envied, an appetite with all academic rigor for the idea and practice of a project that goes beyond the printed matter. Thirst for criticism and hunger for paper.

2. The broth and the ink

If starting at the end of the journal retroactively inscribes the yearning of an editorial project, looking at its beginning tells us about the coordination of different forces and energies to bring it to life. The emergence of the RCC in the 1990s draws, to a large extent, from the critical work carried out during the 1980s. In addition, the historical moment in which the magazine arises is decisive for leftist thought and its drift from the end of the twentieth century to the beginning of the twenty-first. In Chile, this moment is marked by the crossroads of the dictatorial period, the logic of consensus during the transition and the constant general depoliticization of the media as its effect2Nelly Richard, “En torno a la Revista de Crítica Cultural”, Revista De Estudios Hispánicos, 1(22), (2022): 471.. Meanwhile, at the international level, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 produces a disorientation and the real and symbolic demolition of what remained, if any, of the utopian energy of the last century. For this reason, the temper of these times has been read in a melancholic light: we have begun a century with an exhausted political imagination3See: Idelber Avelar, Alegorías de la derrota: la ficción postdictatorial y el trabajo del duelo. Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 2000; Enzo Traverso, “La cultura de la derrota”, in Melancolía de izquierda. Marxismo, historia y memoria. Buenos Aires: Fondo de la Cultura Económica, 2022, 57-110.. The philosopher Sergio Rojas, in a text that deals with an artistic intervention by Ricardo Villarroel in the Mapocho River in 1988, points out: “Not being able to recount history, not being able to count on history, not being able to count on memory, this is precisely our unease in democracy”4Sergio Rojas, “De esas pequeñas fantasías en plena tempestad”, RCC, 16, (1998): 39.. It is a break, in short, between politics and sensibility5Several issues of RCC think about the rough edges of the times. For example, issue 5 of the magazine, dating from July 1992, carried a dossier entitled “Cultura, política y democracia” which dealt with the democratic transition and included contributions by authors such as Tomás Moulian, Pedro Lemebel, Manuel Antonio Garretón, Adriana Valdés, Bernardo Subercaseaux and Raquel Olea, among others. In June 2000, issue 20 of the RCC carried a dossier entitled “Ser de derecha, ser de izquierda”, which included texts by Pierre Bourdieu, Ticio Escobar, Beatriz Sarlo, Andreas Huyssen, Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Frederic Jameson, Jean Franco and Jacques Derrida, among other names. To these examples we can add issue 26, of June 2003, entitled “Neoliberalismo, fabulaciones y complott”; or issue 32, of November 2005, entitled “Marcas y cicatrices (revisitando la dictadura y la transición)”.

Faced with these circumstances, the forms of writing also responded in their own way, and to the same extent the letter suffered the sting of time. In this regard, Roberto Hozven notices a form of “contestation against the authority of culture” that is evident in the essayistic writing genre and its gradual change, which took place during the nineties: self-reflexivity became less a stylistic resource than a mode of representation of a refracted subject or of the different “psychosocial strata” of the national body -if it can be stated in this way6Roberto Hozven, “Mutaciones teóricas del ensayismo chileno”, RCC, 25, (2002): 14. Nelly Richard, Tomás Moulian, Marco Antonio de la Parra, among other voices, give an account of this trance. To this list of names, it is also possible to add the “pictorial-essayistic work” of Eugenio Dittborn, as a plastic expression of the self-reflexivity that synthesizes the writing of the time7“Quizá, por lo mismo, la autorreflexividad sea la forma predominante que sintomatiza hoy día al ‘discurso de la crisis’ en su vertiente conjuntiva de quehacer teórico y de práctica artística; y de la que considero emblemática la obra pictórico-ensayística de Eugenio Dittborn”. Roberto Hozven, “El ensayo chileno e hispanoamericano: interrogantes y réplicas”, RCC, 16, (1998): 29..

In itself, the RCC is a document to approach the saturation of these years, the convulsion of this decade. But the thinking spread in those pages is also the portrait of its management and of a series of sympathies that, directly or indirectly, continued its course in this and other situations (not only the reasons, also the forces tell us about the history of ideas). In this sense, the project was not a simple eruption or a point only imaginable in its time of emergence: the voices and names, the works and references, the theoretical corpus and the formal inclinations tend threads towards a work forged in another context. Of course, trying to find every detail of that story yet to be told would lead to a work as neurotic as it would be impossible, so if we content ourselves with mentioning some moments below, it is because they form trails to assemble a figure of these compromised times.

Feminist thought, in different areas and levels of discussion, runs through the publication. The first issue of the RCC published “Mujeres entre culturas” (“Women between cultures”) by Adriana Valdés and in the third one included “Feminismo y deconstrucción” (“Feminism and deconstruction”) by Cristina de Peretti and Jacques Derrida. Issue 21 included a section entitled “Mujeres y política” (“Women and Politics”), with texts by Kemy Oyarzún, Guadalupe Santa Cruz, Raquel Olea and Cecilia Sanchez, while on the cover of issue 35, published in July 2007, we read the question: “¿Arte de mujeres o política de la diferencia?” (“Women’s art or politics of difference?). To understand this series of contributions and questions we must consider the work of La Casa de la Mujer La Morada, created in 1983, which contributed to the formation of a critical scene and the development of feminist theory during the 1980s in Chile8Julieta Kirkwood, one of the founders of La Morada, was also a professor and researcher in the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO). The International Congress of Latin American Women’s Literature held in 1987 is also an undeniable reference in this regard9Part of the itinerary of this event was included in the book Escribir en los bordes, published by Editorial Cuarto Propio in 1990.“Estar aquí reunidas, significa romper el aislamiento y el ostracismo en que ha vivido la cultura chilena estos catorce años”, said Carmen Berenguer at the time. See Carmen Berenguer, “Nuestra habla del injerto”, Escribir en los bordes. Congreso internacional de Literatura Femenina Latinoamericana / 1987, Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 1990, 16.. To these guidelines, it is also possible to add the discussion on gender and queer theory that the magazine welcomed. In the last issue of the RCC, to mention a clear example, we find the dossier “Matrimonio gay y nuevos parentescos” (“Gay Marriage and New Kinship”), which included texts by Judith Butler, Felipe Rivas San Martín, Karen Atala, Víctor Hugo Robles and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero.

The vector art and politics as a key to read the history of Latin American art, whose theoretical formulation can be found in writings prior to the RCC, also resonates in the magazine. In this regard, it is possible to point out issue 29/30, titled Arte y política. desde 1960 en Chile (“Art and politics. From 1960 in Chile”)10The edition of this issue responded to a project co-organized by ARCIS University, the then National Council for Culture and the Arts and the Faculty of Arts of the University of Chile, which involved the International Colloquium Art and Politics in 2004. This motif or vector, art and politics, is medullar in Nelly Richard’s own critical production. In a book printed in 2018 that gathers voices of critics, theorists and philosophers around artistic practices from 2005 to 2015, Nelly Richard points out, “El vector ‘arte y política’ condensa las principales claves de lectura de la historia del arte latinoamericano”; to later add: “Pero debemos admitir que las resonancias épicas del eco monumental levantado por el vector ‘arte y política’ chocan hoy contra las ramificaciones globales de un capitalismo intensivo que ha trastocado la fabricación, la exhibición y el consumo de los artefactos visuales, generando confusión en torno a los límites de distinción-selección del valor ‘arte’ al propiciar la conmutación de la economía y la cultura en sociedad saturadas de iconicidad por la tecnología de los medios y las industrias de la comunicación.” See: Nelly Richard, Introduction to Arte y política 2005-2015. Proyectos curatoriales, textos críticos y documentación de obras. Santiago: Metales Pesados, 2018, 11-12.. Likewise, the publication of Nelly Richard’s book Margins and Institutions. Art in Chile since 1973 in 1986 was a reference for writing about the arts and the subsequent life of the RCC. Its publication was framed in a special bilingual edition of the 22nd issue of Art & Text, an Australian art criticism magazine in which the Chilean-Australian artist Juan Dávila worked. Veronica Tello and Sebastian Valenzuela-Valdivia have carried out a detailed and unpublished historiographic study on the links and simultaneity of artistic production between Australia and Chile (or the tenuous dialogues between South-South), based on the work of this artist since 1981 in Art & Text. Juan Davila and Paul Taylor, editor and founder of the label, along with editor Paul Foos, who also joined the magazine, produced more than a dozen projects with Chilean artists. These precedents are essential to understand the beginning of the RCC11See: Verónica Tello and Sebastián Valenzuela-Valdivia, “A Partial History of South-South Art Criticism. Juan Dávila’s Collaborations with Art & Text and Chilean Art Workers during the Pinochet Dictatorship, 1981-1990”, Third Text, 6, 35 (2021): 709-731; Verónica Tello and Sebastián Valenzuela-Valdivia, “Southern Atlas: Art Criticism in/out of Chile and Australia during the Pinochet Regime”, Third Text Online (2022): http://www.thirdtext.org/tello-valenzuela-southernatlas (consulted: 03/05/2024).. On the one hand, Juan Dávila participated from the beginning in this magazine and provided the initial financial support for the publication12In its first issues, the editorial board of RCC was composed of Nelly Richard, Juan Dávila, Eugenio Dittborn, Diamela Eltit, Carlos Pérez, Adriana Valdés and Carlos Altamirano. Then, starting with issue 13, the figure of the editorial board changed to an advisory board. Throughout the years this board changed, both with the departure and the integration of new members. We can partially mention some names in the latter group: Marisol Vera, Willy Thayer, Federico Galende, Carlos Ossa. By indicating the names that participated in the project, it is possible to glimpse the affiliation that the RCC shared with other projects and institutions. See: Nelly Richard, Introduction to Debates críticos en América Latina. 36 números de la Revista de Crítica Cultural (1990-2008). Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio / ARCIS, 2008.. On the other hand, in Margins and Institutions Nelly Richard analyzes the artistic practices of the so-called Escena de Avanzada during the period of dictatorial oppression, whose nuclei of reflection were collected in the magazine and, to this day, are an unavoidable critical matrix. For these and other reasons, RCC has been characterized as a magazine that situates, recovers and thinks about the “purposes, proposals and strategies” of the Escena de Avanzada13César Zamorano, “Revista de Crítica Cultural: recomposición de una escena cultural”, Taller de Letras, 54, (2014): 182..

Fig. 1. Portada de Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 29/30, noviembre del 2004.

It is possible to establish, schematically, that if in the 1990s it is the interlocution with the Avanzada what allows us to understand the positionings and guidelines of the RCC, since 2000, the link with the ARCIS University acquires preponderance. In this institution Nelly Richard directed the Diploma in Cultural Criticism between 1997 and 2000 and, later, the Master in Cultural Studies. A research methodology on gratitude has not yet been written (as far as I know), but if we, as readers, stop omitting the acknowledgments in books and follow their traces, we may be able to reconstruct an important part of the genealogy of ideas. These traces, in turn, allow us to understand more accurately the networks that are assembled and disassembled in the history of thought. In the acknowledgements of the 1998 book Residuos y metáforas (“Residues and Metaphors”), Nelly Richard writes:

Aquí en Chile, el Seminario de Crítica Cultural de la Universidad Arcis ha creado un entorno más que propicio para discutir extensamente los temas que atraviesan este libro: agradezco al grupo en general y a Sergio Villalobos en particular la calidad de sus aportes. Y les doy finalmente las gracias a quienes se cruzan más regularmente con mi proyecto de trabajo crítico (Revista de Crítica Cultural incluida), acompañándolo con su amistad e interlocución: a Diamela Eltit por la cercanía de muchos años de historias compartidas; a Carlos Pérez V. y Willy Thayer por su exigente diálogo en torno a crítica, política y escritura14Nelly Richard, Acknowledgments of Residuos y metáforas. (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la Transición). Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 1998, 272..

Apart from these politics of friendship and gratitude, it is necessary to remember, albeit briefly, what ARCIS University meant. It was, undoubtedly, an unprecedented project, viable, at the time, as a space in which left-wing critical thinking had a place and which, as an institution, differed from the neoliberal methods and standards of the universities of its time and ours. The dramatic closure of that institution not only remains as what it could have been; it also has repercussions on the mood of the passing days and on the way in which the university and intellectual work is thought and thinkable. If it is possible to translate the above into a task that concerns us, united to the purpose of this text: we must think about the ceasing of that desire for a magazine and the abrupt cessation, also, of a desire for a university.

Now, and without overlooking the aforementioned ties, in RCC’s issue 8 we find an editorial text that professes the position of the journal: “it is an independent journal, without institutional or academic sponsorship. It is its advertisers and subscribers who make it possible”15RCC, 8, (1994): 7.. Thus, RCC sought, above all, to maintain itself as a project without institutional guidelines, subsisting thanks to advertisers and subscribers and other external sources of funding over time16This condition is different from what today is understood as an independent project, often dependent on state funds such as FONDART for their permanent subsistence. The initial economic contribution, as already mentioned, was provided by Juan Domingo Dávila, who also participated in the editorial board and, later, in the advisory board until the November 2004 publication. Another collaborator was the publishing house founded by Marisol Vera Cuarto Propio, whose name can already be found in the RCC advertisements and is particularly visible between issues 20 and 25, when it collaborated in the publication of the magazine. External support was also provided by the Rockefeller Foundation and the Prince Claus Foundation, as well as the National Council for Books and Reading Fund (specifically, for issues 25 and 26, published in 2002) and the National Fund for Cultural Development and the Arts (for the publication of issue 29/30). Among other decisions, the independence of the RCC with respect to institutional guidelines was also possible because it was never an indexed academic journal, so the inclusion of texts in its pages did not contribute to the academic recognition of an article published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Fig. 2. Colilla de suscripción Revista de Crítica Cultural, noviembre de 1994.

I hope it is clear, from what has been said so far, that the foundation of this desire for a magazine can be traced in the pages of the publication itself. In short: an editorial project of this nature could not take place without what we call management. But the management of the magazine is not only translated into the search for funds for the materialization of printing, but also lies in the trust built up with different interlocutors. For this very reason, the life of the magazine would have no place without those who forged the course of this desire. A special place in this history goes to Ana María Saavedra and Luis Alarcón, who were in charge of the distribution, advertising and subscription of RCC. Ana María Saavedra arrived to Santiago from Concepción at the end of the 1980s to study a master’s degree. It was in 1993, according to what she told me in a conversation, that Nelly Richard invited her to be part of the project17Ana María Saavedra and Luis Alarcón. Interview conducted on January 25, 2024.. From that date until the closing of the magazine, she and Luis Alarcón would be in charge of these and other tasks -such as editing, at specific times- in the magazine.

One last piece of information to add in this section: 1000 copies of each issue of the RCC were printed. These were distributed inside and outside Chile, both in Latin American and North American university departments and in European countries. Copies of the magazine were also offered in some kiosks within the country. “Everything was made with bags. Everything was handmade, domestic and familiar,” says Ana María Saavedra. Ana María and Luis Alarcón especially remember when a considerable number of issues were purchased through a bidding process from the Ministry of Education18Ana María Saavedra and Luis Alarcón. Interview conducted on January 25, 2024..

Fig. 3. Recorte de Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 7, noviembre de 2000, página 4

19Some of the advertisements found in the magazine are true hieroglyphs of stories to be assembled, or small windows to a relatively recent past. We have already mentioned the relationship with Punto de Vista, so it would be interesting to say something about El Café de la Plaza del Mulato Gil, inaugurated in 1982 in a pergola located at 34 José Victorino Lastarria Street. This place was configured as a political and cultural meeting point, according to Nury Gonzalez, who worked in the café with her mother. Politicians, writers, critics, curators and international guests had appointments and meetings in this place. These meetings were so frequent that orders were even left to be picked up at the café’s cashier’s desk. For these frequent appointments a system of exchange was established between the Café de la Plaza del Mulato Gil and the RCC This advertisement refers today to a non-existent place, but it informs us about a history still to be visited

3. (…) de crítica cultural

In a piece of writing that questions the lack of spaces for critique, Pablo Oyarzún argues that the very question of that lack cannot be addressed without also asking about the nature of that space in question. If the lack of a place for critique becomes evident, it is also necessary to inquire about that place where critique should take place. In this way, Oyarzún turns what could appear as a complaint into an incognita (and, therefore, also moves us from demand to desire). He is not focusing on the attributes of a space that enable a correct diffusion, circulation or distribution of ideas, but rather on the very space required by critique. The distance it requires to think, the breath it requires to be practiced:

El espacio crítico, que tiene su dimensión peculiar en la distancia es, ante todo, precisamente esta distancia, es espacio como distancia. De ahí que en buenas cuentas, es el propio discurso el que debe abrir su espacio de inscripción, producir – esto es, reclamar– sus propias condiciones de existencia20Pablo Oyarzún, “Un fragmento sobre la crítica”, in El rabo del ojo. Ejercicios y conatos de crítica. Santiago de Chile: ARCIS, 2003, 242..

The diagnosis of a lack of spaces for critique cannot be thought of without attending to the untimely question that the character of critique implies. It is not possible to inquire about a space for critique without asking the question of the position in which it will take place. To this conjecture it is possible to cross the already announced historical moment of the beginning of the RCC. As Alberto Moreiras points out, thought in the post-dictatorship is “a thought of mourning in the process of constituting itself as such”, so it is not only a “thought of mourning, but also a mourning of thought”21Alberto Moreiras, “Postdictadura y reforma del pensamiento”, RCC, 7, (1993): 28.. As we have seen, this trance of thought during the transition is what the RCC urged to think and the moment in which it situates itself to think; likewise, as a magazine and insofar as it situates a zone for the discussion of ideas and the incursion into debates, it carries within itself the disquieting scar of the place inhabited by critique.

The title of the journal indicates it: it is about cultural critique (“crítica cultural”). The texts we find in it have different perspectives and the authors who sign them come from different disciplines, even from different geographical locations. What allows the gathering of such heterogeneous materials under the rubric of cultural critique? Let us return to the inscription found in RCC’s issue 8, previously mentioned. In that section, we read: “es una revista interdisciplinaria que cruza la literatura, el arte, la filosofía, las ciencias sociales, el feminismo, la política, etc. para analizar y discutir los grandes temas de la sociedad y de la cultura hoy”22RCC, 8, (1994): 7.. In the first place, then, what characterizes this journal of cultural critique is the thinking about society and culture “today” and the diversity of fields that converge for this purpose (until reaching the boredom of “etc.”). To the discussion and analysis of the present or, if we can put it in these terms, to an ontology of the present, miscellaneous forces, different theoretical perspectives and varied disciplinary fields are joined. The question of critique is unsettling, but no less unsettling is its practice.

Fig. 4. Recorte de Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 8, mayo de 1994, página 7.

One way to understand the implications of cultural critique is to ponder its position in relation to the rise of cultural studies and to try to answer the pertinent question of whether the variation between one term and the other corresponds only to a change of label or to a difference between practices. In the case of the RCC, we must then consider the prestidigitation of the name of cultural studies by the notion of cultural critique. According to Paz López, this change does not respond to a merely nominalist dispute, but rather supports a political decision23Paz López, “Mutaciones y contagios. La crítica cultural en Chile”. Text read at the I Congress Cultura en América Latina: Estudios culturales en/ desde América Latina y el Caribe: trayectorias, problemáticas e imaginarios, Aguascalientes, México, October 2014.. Not only have cultural studies dealt with controversial issues, but also cultural studies itself corresponds to a litigious object. In 2010, Néstor García Canclini stated: “La duda crónica sobre qué son los Estudios Culturales es una pregunta para diccionarios”24Néstor García Canclini, “Estudios Culturales: ¿Un saber en estado de diccionario?”, En torno a los estudios culturales. Localidades, trayectorias y disputas, edited by Nelly Richard. Santiago de Chile: Editorial ARCIS, CLACSO, 2010, 123. That doubt would be the current state for that disciplinary yeast, fermented in departments of cultural studies and proliferated in dictionary entries for what at some point tried to be an elusive knowledge. Discussions on a finished definition, however, have not been as beneficial to their purposes as their own experiences have been. Nelly Richard has emphasized how, in itself, the discussion around cultural studies has been productive as a critical factor: “Algunas de las disputas en torno a los Estudios Culturales en América Latina han resultado, en sus intersecciones y bifurcaciones críticas, más interesantes que el relevamiento canónico de sus definiciones de contenidos obsesionadas con la estandarización académica”25Nelly Richard, “Respuestas a un Cuestionario: posiciones y situaciones”, En torno a los estudios culturales. Localidades, trayectorias y disputas, edited by Nelly Richard. Santiago de Chile: Editorial ARCIS, CLACSO: 2010, 75..

One way of accessing cultural studies would be its genealogical inquiry, from its disciplinary beginnings in the 1960s in England, with the names of Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall in Birmingham and Raymond Williams in Cambridge, to its parking in the United States. But it is also possible to attend to a certain way of doing politics, or a view of that political work, driven by the student movement of the last century, with the cases of the sixties and eighties around the globe. In this sense, cultural studies would be both recipients and conductors of a “cultural politics at the level of everyday life”, through the dialogue established between philosophy and political actuality. Because of this perspective, a thinker and scholar such as Bruno Bosteels went so far as to affirm that: “many of us who work today in cultural studies are effectively the collective heirs of ’68”26Bruno Bosteels, El marxismo en América Latina. Nuevos caminos al comunismo. Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional, 2013, 48.. This concern for the historical circumstance would integrate the knowledge and tradition of cultural studies.

In a lecture delivered in 1997, and published in the fifteenth issue of the RCC, Beatriz Sarlo underlines the change of paradigm of reading and reception of thinkers in order to understand the condition of cultural studies. Thus, to the names already mentioned from the Anglo-Saxon orbit, should be added the signature of Walter Benjamin, “who ceased to be read as a critic and thinker to become an innocent forerunner of academic studies on urban cultures,” according to Sarlo27Beatriz Sarlo, “Los estudios culturales y la crítica literaria en la encrucijada valorativa”, RCC, 15, (1997): 38.. When considering the mutation in the sympathy of the reading community, the geopolitical factors that influence such variations should not be overlooked. This disposition between dissimilar forces and powers is evident in the circulation of critical writings, since it also traces a horizon of expectations about what a subject wants and can enunciate from his or her geography, gender or other determinant. Beatriz Sarlo will state towards the end of her lecture: “Todo parece indicar que los latinoamericanos debemos producir objetos adecuados al análisis cultural, mientras que Otros (básicamente los europeos) tienen el derecho de producir objetos adecuados a la crítica de arte”28Beatriz Sarlo, “Los estudios culturales y la crítica literaria en la encrucijada valorativa”, RCC, 15, (1997): 38.. Instead of disregarding the maxim of cultural exports and imports, this constant will be taken up by cultural critique, as a situated reflection on language, or a situation for thought. As an understanding of the place of enunciation that demarcates, in addition and in itself, a position, a space for critique and for thinking critique.

To the complicity between RCC and Punto de vista, previously suggested, we should also add the name of Marta Lamas as director of the magazine Debate feminista, founded in 1990 in Mexico. In all three cases, these are periodicals associated with a name, either in their interlocutions or in the impetus of the editorial project. In the case of RCC, the association with the name of Nelly Richard is clear insofar as the notion of cultural critique embraces her own work and intellectual project. In 1998, this author published Residuos y metáforas (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la Transición), a book that not only gives us clues about the term in question by its title, but also develops what would be the particularity of cultural critique. On the one hand, the text points out that it establishes a “living dialogue with the context and its ongoing productions; in the micro-textures of local and contingent practices and in the social heterogeneity of its dynamic of signs that open up to the unfinished formulations of the new”; on the other hand, Richard will also establish that it is not simply a matter of “criticizing the design of the present” with pre-established molds that are extracted from that same present, with a mere inversion of meanings that work on the same board29Nelly Richard, Acknowledgments of Residuos y metáforas. (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la Transición), Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 1998, 16.. With precision, Federico Galende stated that the understanding of current events pursued by the critical discourse runs the risk of being “the official metaphor of an inert epochal realism”30Federico Galende, “Un desmemoriado espíritu de época. Tribulaciones y desdichas en torno a los Estudios Culturales (una réplica a John Beverley)”, RCC, 13, (1996): 53.. An epochal spirit that, by dint of categorical packages, obstructs the singularity of the other. What is it, then, that differentiates cultural critique? Instead, Richard continues, it explores “the diagonals that look into the less regular and concerted -more disconcerting- zones of the environment”31Nelly Richard, Introduction to Residuos y metáforas. (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la Transición), Santiago: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 1998, 13. It is, cultural critique, a diagonal vision, an anamorphosis that requires the contortion of the gaze to distinguish distortions and anomalies.

To the attempt to read the present without succumbing to its logic, or to the differentiation of the senses without agreeing with common sense, Nelly Richard has also added the feminist character, or rather, the model that feminist critique gives to cultural critique32En a 2009 texts published in Debate feminista, Nelly Richard writes: “La crítica feminista es crítica cultural en un doble sentido: 1) es crítica dela cultura, en tanto examina los regímenes de producción y representación de los signos que escenifican las complicidades de poder entre discurso, ideología, representación e interpretación en todo aquello que circula y se intercambia como palabra, gesto e imagen, y 2) es una crítica de la socie-dad realizada desde la cultura, que reflexiona sobre lo social incorporando la simbolicidad del trabajo expresivo de las retóricas y las narrativas a su análisis de las luchas de identidad y de las fuerzas de cambio”. See: Nelly Richard, “La crítica feminista como modelo de la crítica cultural”, Debate feminista, 40, (2009): 79.. This is a relationship that we have already exposed even in the beginnings of the critical energy that the RCC gathers. A clear example of this model provided by feminist criticism is its proximity to discourse analysis. A broad definition of discourse, in fact, includes not only plots of linguistic signs, but also of semiotic systems in general and, by attending to these formations, makes it possible to understand power relations and the use, continuity and repercussions of systematic violence, as well as its denunciation in factual and symbolic forms.

The cover of the first issue of RCC uses the photograph of “the freedom traveler” by Mathias Rust, a German pilot who, in 1987, at the age of 19, flies to Moscow, evading the Soviet air defense. This image, which is part of Lotty Rosenfeld’s video work, as several voices have already pointed out, is the visual referent that marks the publication’s emergence through the “disruption of borders”33See: Macarena Silva, “La Revista de Crítica Cultural y el trabajo de Nelly Richard. Estéticas transdisciplinarias y escenas de escritura”, Taller de Letras, 54, (2014): 167-180. probed by cultural critics. A very brief editorial text states this:

Esta imagen de un trabajo de arte que convierte las mutaciones ideológicas y los cambios políticos (Chile, Alemania, Unión Soviética) en material a editar mediante junturas y cruzamientos de citas en tránsito; esta imagen de un trabajo de arte invierte líneas divisorias y rayas separativas, le imprime a este primer número la marca inquieta de su referencia o trastocamientos de fronteras e identidades sociales, culturales y nacionales34Editorial text in RCC, 1, (1990)..

The sensibility of the image of the traveler, then, appears before the historical weight of an international transformation, as well as in the repercussions of local political transit and the shipwrecks of meaning resulting from violence. It is an allegory, in turn, of the semantization of the crossing of disciplinary borders on the part of cultural critique, and it also shares that route of the gathered international voices. In a 2001 text, Nelly Richard takes up these border articulations to provide a clearing in the forest of descriptions and definitions available to cultural critique:

A mitad de camino entre los estudios culturales, la filosofía de la deconstrucción, la teoría crítica y el neoensayismo, la crítica cultural se desliza entre disciplina y disciplina mediante una práctica fronteriza de la escritura que analiza las articulaciones de poder de lo social y de lo cultural, pero sin dejar de lado las complejas refracciones simbólico-culturales de la estética35Nelly Richard, “Globalización Académica, Estudios culturales y crítica latinoamericana”, Estudios Latinoamericanos sobre Cultura y Transformaciones Sociales en tiempos de globalización, Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2001, 195..

Fig. 5 y 6. Portada y editorial de Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 1, mayo de 1990

The interregnum, the border or the margin. The in-between zone as a topology for criticism allows us to understand its mode of writing, even to savor its stylistic impulses. This image, by the way, is intimately linked to Nelly Richard’s work. In the editorial opening of issue 14 of Papel máquina magazine, dedicated to Richard’s thought, Alejandra Castillo will return precisely to these topics and the minority and elusive character of critique36Alejandra Castillo, Editorial of Papel máquina, 14, (2020): 10.. In this sense, explaining the notion of cultural critique projected by RCC on the basis of these terms informs us more about the orientation of the editorial project than about the direction or perspective of each text included in the magazine. It is more a controversial interpretation of critical work than a user’s manual.

The elusive condition of cultural critique is also the place to which critique has been directed, carried out by names like Hernan Vidal or Ana del Sarto37See: Ana del Sarto, Sospecha y goce: una genealogía de la crítica cultural en Chile. Ensayo / Crítica cultural, Santiago: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2010; Hernán Vidal, “Revista de Crítica Cultural”, Tres argumentaciones postmodernistas en Chile, Santiago: Mosquito, 1998.. In general, there has been a rampant acceptance of postmodernism and its logics, inasmuch as the theoretical discourse, in general as an agglutinating signifier, would also be a symptom of the spirit of the times, as Frederic Jameson has critically exposed in his time. Much more subtle and challenging is the consideration of the analysis of temporality, or the demands of an ontology of the present that Jameson himself points out with respect to a cultural analysis. In this sense, the author warns that “the very word culture presents a danger, insofar as it presupposes a certain separate and semi-autonomous space in the social totality that can be examined in itself in order to reconnect it later in some way with other spaces”38Frederic Jameson, “Estética de la singularidad”, New Left Review, 92, (2015): 110.. This provocation regarding what a cultural analysis does and does not imply, I believe, is unavoidable with respect to what is also understood by cultural critique and what has been its trajectory in recent history.

4. The visual in the fingertips, that skin of the magazine

A desire is also a stubbornness, an insistence. The collective forces that the RCC summoned were not only translated into textual creations, but also into artists’ interventions. Whether in the design of an issue, whether in the inclusion of a work, visuality was not only addressed as a subject of study or critical motif by the reading entries that occupied the pages of the publication; it also took place in the reflection of the images in the images themselves. Thus, instead of occupying an illustrative or decorative place, they were positioned in the theoretical and critical attempt that the project pursued. Of course, if their ultimate purpose was not to embellish, this also explains the opacity and visual weight that we find when we open some issues of the magazine. In this regard, it is possible to mention at least three ways in which the proposed link becomes evident: first, in the visualization of the first issues of the magazine, carried out by invited artists; then, in the celebration of the magazine’s tenth anniversary; and, finally, in the specific intervention of artists for certain issues. I will not make a detailed exposition, but I will dwell on some of these moments.

The 31st issue of the RCC was entitled “La crítica. Revistas literarias, académicas y culturales”. In this issue there is a text by Miguel Dalmaroni that underlines the visuality of the RCC and “the close links it (…) maintains with ‘art’, on the one hand as the axis of its discourse, and on the other as the inclusion, both in its graphic realization and in the group that manages the project, of the work of writers and plastic artists”39Miguel Dalmaroni, “Dictaduras, memoria y modos de narrar: Punto de vista, Confines, Revista de Critica Cultural, H.I.J.O.S”, in RCC, 31, (2005): 30-39.. This shows the awareness that already existed, during the life of the project, about this work between texts and images. Certainly, in the Chilean context, the solidarity between text and image has precedents in printed publications (an example of this is the CAL magazine)40It will be in CAL where for the first time the transforming visual arts program will be printed, within a framework of debate regarding the functions and possibilities of work and critique, visual arts publication, gallery and museum, says Nicolás Raveu in: Introduction to Revista cal, una historia, Cociña, Soria Editores.. However, the uniqueness of RCC lies in the duration of the project, as well as in the breadth of the group of artists who participated in one way or another in the magazine.

The graphic design of RCC was in charge of Carlos Altamirano in the first issues, then Guillermo Feuerhake, José Errázuriz and, in the last issues, Rosa Espino. On the other hand, in the early years of the magazine, there were guest visualizers or artists who contributed with images and with the visual idea of certain issues (Eugenio Dittborn, Arturo Duclos, Carlos Altamirano and Gonzalo Diaz are among them). We can make a brief overview of these interventions, only with the purpose of dimensioning the operations involved. For example, in the frontal retreat of issue 2 of RCC, in which Eugenio Dittborn collaborated, the artist writes as a prelude: “es preciso señalar que la visualidad que en esta revista puebla invariablemente el borde de sus páginas, ha sido diseñada para ser travesía ornamental, campo de injertos y cripta mestiza”41Eugenio Dittborn, “FIGURENSE”, RCC, 2, (1990).. The resource of marginalia, or the writing on the edges of the pages, thus becomes an artistic operation that is akin to the reflection of the five hundred years of the so-called “discovery of America” that summons this issue of the RCC.

Fig. 7. Intervención de Eugenio Dittborn en retiro frontal de Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 2, noviembre de 1990.

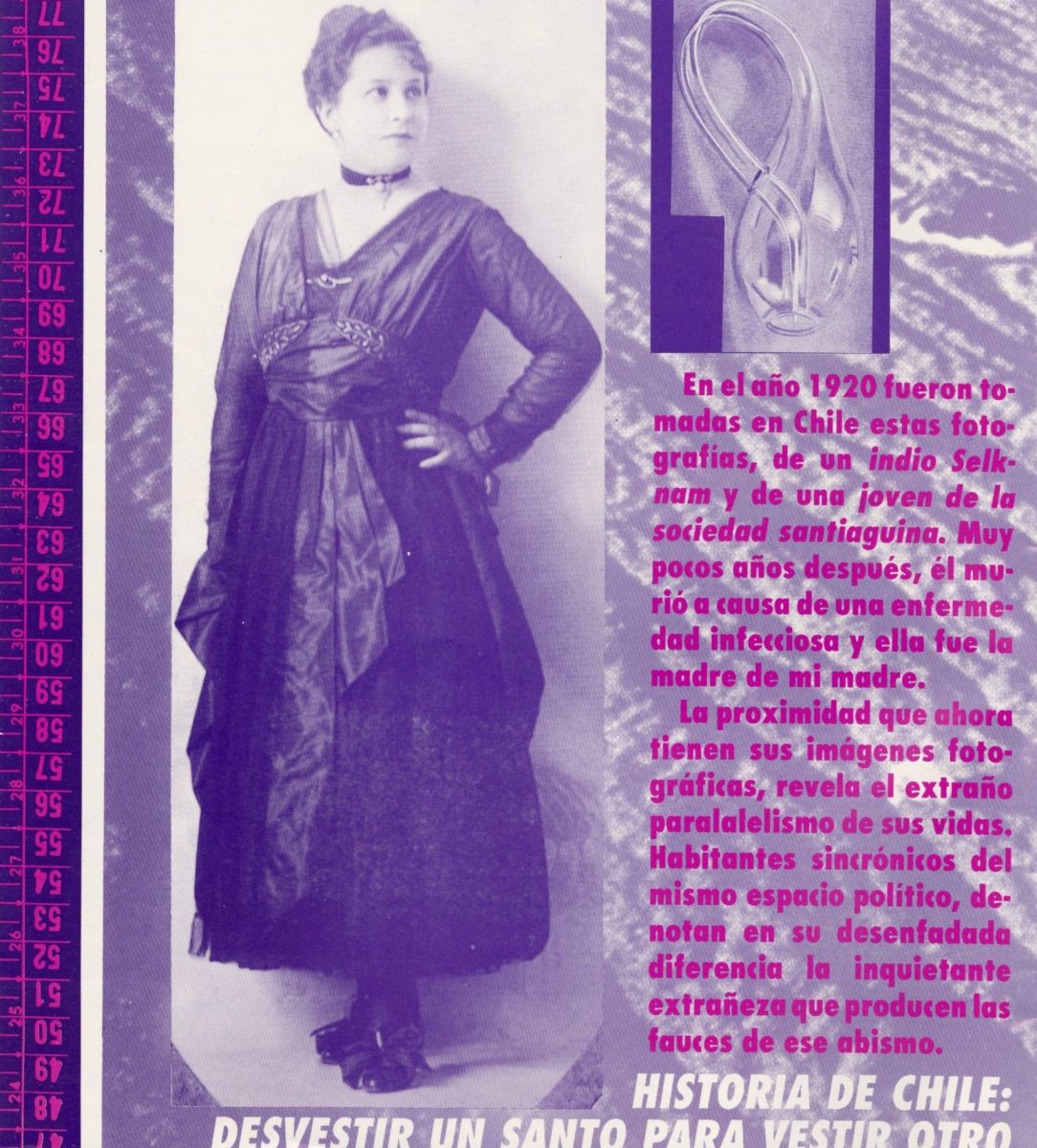

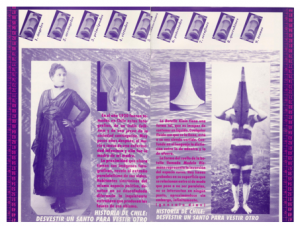

Another case is that of issue 3, where Arturo Duclos iconographically works the Tree of Life with different elements, as if it were a random esotericism given from one image to other images. Carlos Altamirano, on the other hand, uses both withdrawals of the magazine in issue 4 to include a text on “domestic icons”, their “opaque flashes of meaning” and their consubstantial lack of an epic. In issue 5, Gonzalo Díaz takes advantage of both retreats for the inclusion of a piece that reflects, in turn, on parallels. In this case, two photographs taken in 1920 are found at both ends of the magazine, separated by the general body of texts that make up the issue. One image is that of a Selk’ nam and the other of “a young woman from Santiago society”. As we read in the text written by Díaz, the proximity of both figures reveals “the strange parallelism of their lives”.

Figs. 8 y 9. Intervenciones de Gonzalo Díaz en Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 5, julio de 1992.

The above gives us a clue to inquire into the places of exhibition and circulation of works that are not so profusely attended. Not of circulation of images of works, but of works that are thought and think in the very support in which they are found. Between texts and pages, between covers and retreats. Where art has been talked about outside the space of the museum or the conventional frameworks, we can also find works giving body or forming part of the integument of a magazine. We could say that in some cases we are dealing with pensive images -as Jacques Rancière has put it-, images that reflect on their own medium with their own means42Jacques Rancière, “La imagen pensativa”, El espectador emancipado, Buenos Aires: Manantial, 2008, pp. 105-137.

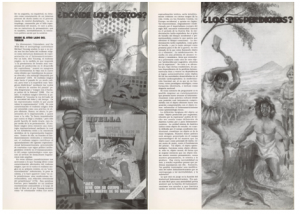

The publication of issue number 10 of RCC, in May 1995, is another case that invites us to think about the place of visuality in this magazine. For this occasion, six artists (Arturo Duclos, Lotty Rosenfeld, Carlos Altamirano, Gonzalo Díaz, Paz Errázuriz and Juan Dávila) were invited to participate in a group exhibition entitled ¿Dónde los restos? ¿En qué zona los desperdicios? at the Galería Gabriela Mistral. The different works presented in this show, which reflected on loss, surplus, open spaces and borders, were also part of the visualization of RCC‘s number ten issue. Moreover, each of the invited artists participated in this edition of the magazine with an unpublished work, and each work bore the same title. At the same time, the publication of this issue included texts that reflected on the same theme of the exhibition. On the pages next to the images are inscriptions by Federico Galende, Diamela Eltit, Francisco Olea, Hernán Velázquez, Eugenia Brito, Teresa Bustos, Willy Thayer, Pablo Oyarzún, Olga Grau, Marcelo Mellado and Francisco Brugnoli43Recently, in the context of the exhibition Morfologías sensibles (2023-2024) at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Santiago de Chile, when visiting Chilean visuality 50 years after the military coup, the inclusion of the graphic art in issue 10 of the RCC was reviewed, with special attention to the names of Diaz, Dittborn, Duclos and Dávila.

Figs. 10 y 11. Intervenciones de Juan Domingo Dávila en Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 10, mayo de 1995, pp. 51 y 53.

Figs. 12 y 13. Intervenciones de Lotty Rosenfeld en Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 10, mayo de 1995, pp. 27 y 29.

Figs. 14 y 15. Intervenciones de Paz Errázuriz en Revista de Crítica Cultural N° 10, mayo de 1995, pp. 45 y 47.

This event is evidence of the work carried out by artists in collaboration with the RCC. Moreover, the issue itself is emblematic of the theoretical conatus between visuality and writing, a reflexive parity in the diversity of modes and perspectives on the same problem thought and sensitized by artists, writers, critics and essayists. Of course, the question ¿Dónde los restos? (“Where are the remains?”) evokes the political violence of the dictatorial period and its prolongation during the post-dictatorship in the form of forced disappearance and its continuity in the complicit silence. Thus, the question resonates in his time and even in ours. Among the different voices and looks these figures are recovered and thought, even demanded.

There are also other approaches that, like the image of the freedom traveler in Loty Rosenfeld’s video-work, think about the very status of critique based on the questions of the exhibition. Federico Galende, for example, reflects on the remains, the excesses and the wastes as a primary critical element: “la crítica oye el susurro arcaico de las conciencias que se rehúsan a ser deportadas a un mundo sin legajos, o a cumplir su misión entre las toscas redes de las regularidades sociales”44Federico Galende, “La insurrección de las sobras”, RCC, 10, (1995): 24.. Above all, the rest is that which critique savors in the time of the present, contrary to the smooth screen of the given or the apparently codified cultural datum. In this sense, critique registers the roughness of its present, where the critical moment is found by refraction, that which the prevailing ideology would pretend to suppress as its excess. Galende continues: “Molestan los restos, si, acaso porque estos son la cosa en su estado de mayor crispación, conmoción latente que acecha con irrefrenables balbuceos y burladas esfumaturas”45Federico Galende, “La insurrección de las sobras”, RCC, 10, (1995): 24..

In addition to the above cases, there are singular interventions by artists in certain issues of the RCC that are worth mentioning. In particular, I would like to return to an image that Nury Gonzalez introduces in the thirteenth issue of the publication, since it reveals exemplarily the issue that concerns us. It is a work that not only intervenes in the magazine, but also reflects on its support and the very desire that sustains it. In this case, the image exists only as an image for the publication. The intervention of the head and the phrase on the blackboard by Jacques Lacan make this explicit: “of a discourse that would not be of the semblant”, we would read in English.

In the face of the classical dichotomy between essence and appearance, Professor L situates the notion of semblance not in opposition, but as the reverse of truth. There would be no discourse without semblance, because it requires the discourse of a body to be seen in its pursuit of the real. Semblance is that which is given to be seen; but not by being given to be seen does it become part of the realm of illusions as falsehood. On the political plane we have experienced it forcefully: a discourse does not cease to have effects on reality because it is less true. We would go so far as to say that the semblants are at our side and are the political springs par excellence.

By underlining this operation of discourse, by bringing up the semblance on a textile and a verse of the national anthem (a verse that reminds us, in turn, that as a national project we are the semblance of paradise, or “the happy copy of Eden”), Nury Gonzalez’s work also indicates the entanglements in which the texts necessarily incur. Instead of ratifying the supposed transparency of language or even of images, the critic would also think of the opacity of its objects and resources. That is to say, in its condition of semblance or, as it is commonly said, in its own materiality.

In the remains, the waste and the semblants, cultural criticism thinks. With them, in them, from them.

5. Final words

The reader should not be surprised. At least in its linguistic dimension, the expression of ideas requires someone to express them and, as if that were not enough, it also requires spaces for thought not to be extinguished in its own idea of an idea, but to have the possibility of leading to dialogue, discussion (and even insults, why not say it) with other interlocutors. This essay has sought to trace the history and impetus of one such space. On the occasion of the publication of Crítica y política, a book that gathers conversations between Nelly Richard, Miguel Valderrama and Alejandra Castillo, raul rodriguez freire writes about the imperious need to return to the textures and diverse moments of critique. “The cost,” says the author, ”will be our own disappearance, unless the generations to come know where to learn from”46Raúl Rodríguez Freire, “La crítica cultural en el siglo XXI. A propósito de Crítica y política de Nelly Richard”, Taller de Letras, 54, (2014): 165.. The purpose of the reading of the RCC here, likewise, has been to sift through a series of texts from which it is possible to extract that learning from critique. I believe it has become clear that it is not a matter of a content to declaim; this learning has, rather -and I insist-, the form and the distance of a desire.

All issues of the RCC are digitized at the Center for Documentation and Research on Left Culture (CeDInCi). In the presentation of its web page, it is stated: “América Latina ha sido y es un continente de revistas”. This has been the way to exercise polemic, to encourage the circulation of ideas and to create a community as silent as it is boisterous of friends of print. The history that we have concocted, then, should not forget neither the form of the essay nor the format of periodicals as records and supports of Latin American thought. That periodicity and haste is what also allows and requires the essays gathered in the journals, and in this case the RCC, to think about their present. To critically direct the gaze towards the conjuncture. What we have tried to study here, then, is not only a series of texts gathered in the title of a publication -an archive available among others-, but the strength to gather and the energy to establish networks and interlocutors, despite the instability of the medium and the wear and tear of the work itself.

References

Avelar, Idelber. Alegorías de la derrota: la ficción postdictatorial y el trabajo del duelo. Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 2000.

Beverly, John. “Estudios culturales y vocación política”. Revista de Crítica Cultural, 12, (1996): 46-53.

Berenguer, Carmen. “Nuestra habla del injerto”. Escribir en los bordes. Congreso internacional de Literatura Femenina Latinoamericana / 1987. Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 1990: 13-16.

Dalmaroni, Miguel. “Dictaduras, memoria y modos de narrar: Punto de vista, Confines, Revista de Critica Cultural, H.I.J.O.S”. Revista de Crítica Cultural, 31, (2005): 30-39.

Richard, Nelly (ed.). Debates críticos en América Latina. 36 números de la Revista de Crítica Cultural (1990-2008). Santiago: Cuarto Propio / ARCIS, 2008.

Del Sarto, Ana. Sospecha y goce: una genealogía de la crítica cultural en Chile. Ensayo / Crítica cultural. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2010.

Derrida, Jacques. “Globalización del mercado universitario, traducción y restos”. Revista de Crítica Cultural, 25, (2002): 23-25.

Galende, Federico. “La insurrección de las sobras”. Revista de Crítica Cultural, 10, (1995): 24.

—–. “Un desmemoriado espíritu de época. Tribulaciones y desdichas en torno a los estudios culturales”. Revista de Crítica Cultural, 13, (1996): 25-28.

García Canclini, Néstor. “Estudios Culturales: ¿Un saber en estado de diccionario?” En torno a los estudios culturales. Localidades, trayectorias y disputas, edited by Nelly Richard, Santiago de Chile: Editorial ARCIS, CLACSO, 2010, 123-132.

Jameson, Frederic. “Estética de la singularidad”. New Left Review, 92, (2015): 109-142.

López, Paz. “Mutaciones y contagios. La crítica cultural en Chile”. Text read at the I Congress Cultura en América Latina: Estudios culturales en/ desde América Latina y el Caribe: trayectorias, problemáticas e imaginarios, Aguascalientes, México, October 2014

Hozven, Roberto. “El ensayo chileno e hispanoamericano: interrogantes y réplicas”, Revista de Crítica Cultural, 16, (1998): 28-29.

—–. “Mutaciones teóricas del ensayismo chileno”, Revista de Crítica Cultural, 25, (2002): 14.

Moreiras, Alberto. “Postdictadura y reforma del pensamiento”. Revista de Crítica Cultural, 7, (1993): 27-35.

Oyarzún, Pablo. “Un fragmento sobre la crítica”. En El rabo del ojo. Ejercicios y conatos de crítica. Santiago: ARCIS, 2003, 239-242.

Piñero, Gabriela. “Crítica cultural y políticas de la mirada (Richard)”. Ruptura y continuidad. Crítica de arte desde América Latina. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2019, 161-184.

Rancière, Jacques. “La imagen pensativa”. El espectador emancipado, Buenos Aires: Manantial, 2008, 105-137.

Ramírez, Carolina. “Producir una empresa editorial. El caso de la Revista de Crítica Cultural en Chile”. Alpha, 26, (2008): 261-279.

Richard, Nelly. “En torno a la Revista de Crítica Cultural”. Revista De Estudios Hispánicos, 1(22), (2022): 471–479.

—–. Introduction to Arte y política 2005-2015. Proyectos curatoriales, textos críticos y documentación de obras. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2018, 11-15.

—–. Introduction to Residuos y metáforas. (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la Transición. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 1998.

—–. “La crítica feminista como modelo de crítica cultural”. Debate feminista, 40, (2009): 75-85.

—–. “Globalización Académica, Estudios culturales y crítica latinoamericana”. In: Estudios Latinoamericanos sobre Cultura y Transformaciones Sociales en tiempos de globalización, compiled by Daniel Mato. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2001, 185-198.

—–. “Respuestas a un Cuestionario: posiciones y situaciones. Nelly Richard”, in En torno a los estudios culturales. Localidades, trayectorias y disputas, edited by Nelly Richard. Santiago de Chile: Editorial ARCIS, CLACSO, 2010, 67-82.

Raveu, Nicolás. Introduction to Revista cal, una historia, Cociña, Soria Editores.

rodríguez freire, raúl. “La crítica cultural en el siglo XXI. A propósito de Crítica y política de Nelly Richard”. Taller de Letras, 54, (2014): 159-164.

Rojas, Sergio. “De esas pequeñas fantasías en plena tempestad”, Revista de Crítica Cultural, 16, (1998): 36-40.

Sarlo, Beatriz. “Los estudios culturales y la crítica literaria en la encrucijada valorativa”, Revista de Crítica Cultural, 15, (1997): 23-38.

Silva, Macarena. “La Revista de Crítica Cultural y el trabajo de Nelly Richard. Estéticas transdisciplinarias y escenas de escritura.” Taller de Letras, 54, (2014): 167-180.

Tello, Verónica / Valenzuela-Valdivia, Sebastián (2021): “A Partial History of South-South Art Criticism. Juan Dávila’s Collaborations with Art & Text and Chilean Art Workers during the Pinochet Dictatorship, 1981-1990”. In: Third Text, 6, 35, pp. 709-731.

Tello, Verónica / Valenzuela-Valdivia, Sebastián (2022): “Southern Atlas: Art Criticism in/out of Chile and Australia during the Pinochet Regime”. In: Third Text Online. http://www.thirdtext.org/tello-valenzuela-southernatlas

Enzo Traverso, “La cultura de la derrota”, en Melancolía de izquierda. Marxismo, historia y memoria, Buenos Aires: Fondo de la Cultura Económica, 2022), 57-110.

Valdés, Adriana. “A los pies de la letra: Arte y escritura en Chile”. Memorias visuales. Arte contemporáneo en Chile. Santiago: Metales Pesados, 2006, 277-303.

Vidal, Hernán. “Revista de Crítica Cultural”. Tres argumentaciones postmodernistas en Chile. Santiago: Mosquito, 1998.

Yúdice, George. “Estudios culturales y sociedad civil”, en Revista de Crítica Cultural, 8, (1994): 44-53.

Zamorano, César. “Revista de Crítica Cultural: recomposición de una escena cultural”. Taller de Letras, 54, (2024): 181-192.