An event must end in some way before its narrative can begin

-Christian Metz

What would happen if for a moment we stopped believing in fixed and binary categories such as man/woman, worker/vagrant, black/white, beauty/ugliness, saving/waste, law/punishment, and instead tried to search in the concepts themselves for small cracks, folds and creases where new notions not yet seen begin to erode the foundations of what we define as society? This is an important issue to start talking about Diego Bianchi’s work and one of the limits with which his work experiments: to erode the system of social categories that connect objects and bodies, making them enter into a drift of meanings that is often impossible to reduce to an already known or domesticated category.

Diego Bianchi’s works are seemingly random connections with found materials that the artist himself collects in the streets near his workshop in Warnes, Buenos Aires, an area characterized by the legal and illegal trade of all kinds of car pieces and numerous shops dedicated to their repair and scrapping. Bianchi works with multiple waste materials, ranging from plastic to metal, and through its own translation process new geometric figures emerge, straight lines, broken or twisted angles that do not point to an end, but expand into imaginary areas and volumes. These structures work in combination with objects made of glass, wood, paper, foam and other strangely folded materials. They are speculative and temporary bodies that lean, rise, and are intertwined in a temporary collapse, thus activating the power of sculpture, in the best surrealist tradition as Georges Perec would pose: the ability to remain in space as an object of libido and desire whose identity can never be defined.

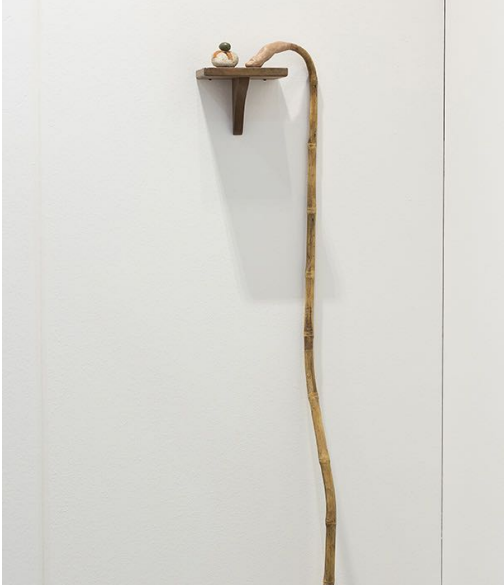

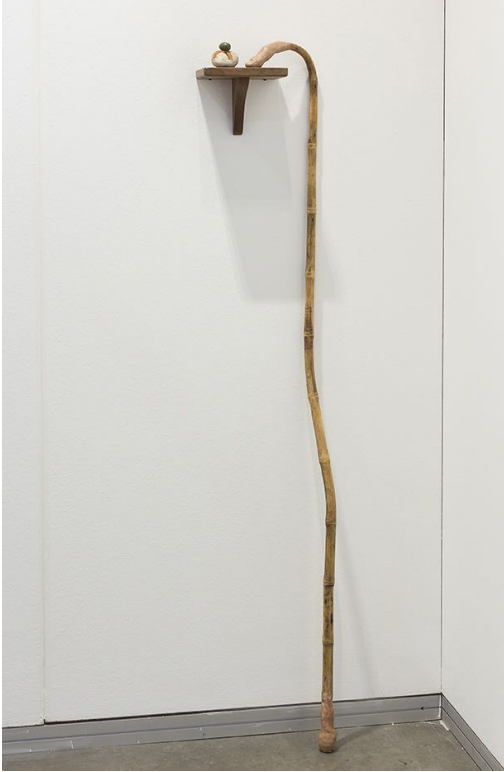

Fig. 1. Diego Bianchi, Posiciones en la heladera, 2016

In Diego Bianchi’s work, the field of study of this relationship between art and politics has for years been the body understood not as a space of unidimensional revolution, but as a temporal, sexually-fluid changing machine. The components of this study are the resistance as a friction point for the bodies, the rebellion as a flux and, on another level, power as the great administrator of seductive experiences of pleasure and pain. There is a certain point in which these works, cynically, cleverly and with a good dose of humor, intertwine Karl Marx with Artaud. What makes a man a man, a woman a woman, someone a black or white person, or the very distinction between human and animal? In this sense, Bianchi’s linguistic turn and social constructivist critique closely resembles Marx’s critique of commodity fetishism. From a naive perspective, value seems to be something that resides in the commodity itself. What Marx demonstrated in such a brilliant way was how value is not a property of the object itself, say a piece of gold, but something that arises from social relations that hide relations of domination and exploitation. When we break through the illusion of the commodity, the possibility of emancipation opens up as we can then understand these social relations. The same happens in the case of the signifying apparatus and the way it structures identities, the world and social relations. We can see, for example, discourses as performative forms by which people name and classify themselves as healthy and sick, addicts and doctors. It seems that Bianchi is telling us at every moment in his work: Let us not deceive ourselves, property and its attributes in itself are a lie. Remove from people’s lives categories such as meaning, ugliness, beauty, intelligence, stupidity, status, and from there we will begin to experience with our bodies a new social field.

Fig. 2. Diego Bianchi, Framing Time, 2019

These issues of the body subjected to the social field can be seen throughout different works and interventions carried out over time, works that populate with stark, luminescent and strangely alive materialities a world where Bianchi speaks of both the sweetest ecstasy and a terrifying pain. To look at Diego Bianchi’s work is to think of sculpture and the body in experiential terms, as fields of tension between the affective forces of abjection and attraction, this tense dystopia of bodies and their friction with the Real, that often exposes one of the main questions of our time: is the body immanent to the political collective and human communication?

Perhaps that is why in his performative video Inflation there is something that denies the possibility of human community as a sign of political plurality. It seems that all that is on the margins, that is, the people who were not included in the progressive project of modernization of our states, are represented as a walking biomass immersed in entropy. The metaphor of this mass, frozen outside the law on the threshold of nature and culture, between the human, mutant and the animal, is the image of the defective clones of the economic and political systems, the debris of society, who do not even suspect in their semi-animate ignorance that they are flawed, but as walking sculptures can only give an aesthetic image to the world.

Fig. 3. Diego Bianchi, Inflation, 2021

In this dehumanized and erotic carnival that Bianchi presents us with, he intelligently mixes pain, animal delight and barbaric divination; as if the withdrawal of the legal network and the instance of visibilization of alternate bodies would automatically suspend politics and faith in its economic models of progress. In this orgy of denied and collective bodies, a demonstration of the body parts themselves, which suddenly appear in front of the spectator as members of a collective without a specific reason, is not enough. It would seem that these walking biomass connections can only respond to institutionalized practices by denying and ritualizing labor, death, pain and the desire to translate experience into an abject artistic object. This mass represents something more than human: an ideologeme; or -when the ideologeme is represented by other attributes (media technologies, types of consumption, companies and corporations)- it acquires the status of a superfluous thing, trash, suitable material that Bianchi dismembers, assembles and puts back together in new couplings.

The disintegration of this waste materials becomes a form of ecstasy that testifies to the presence of something unassimilable in the objects, even in the process of physical reassembly. In these bodies there are no prohibitions, a penis and a hand can be next to a lip that at the same time is an iron bar attached to a piece of plastic creating a second life as members exposed to other types of relationships and processes. These assemblages are a rebellion against the oedipal order that makes only the forbidden seem desirable. These bodies move in a violent and dystopian temporality, they are in themselves a “movement against the grain” of power and its media representations of history that form fixed lines of routes and readings. History, as you know, is written by the victors as a continuous, linear, homogeneous process in which each specific episode is subordinated to the logic of the narrative domain.

Will it be the same for the bodies?

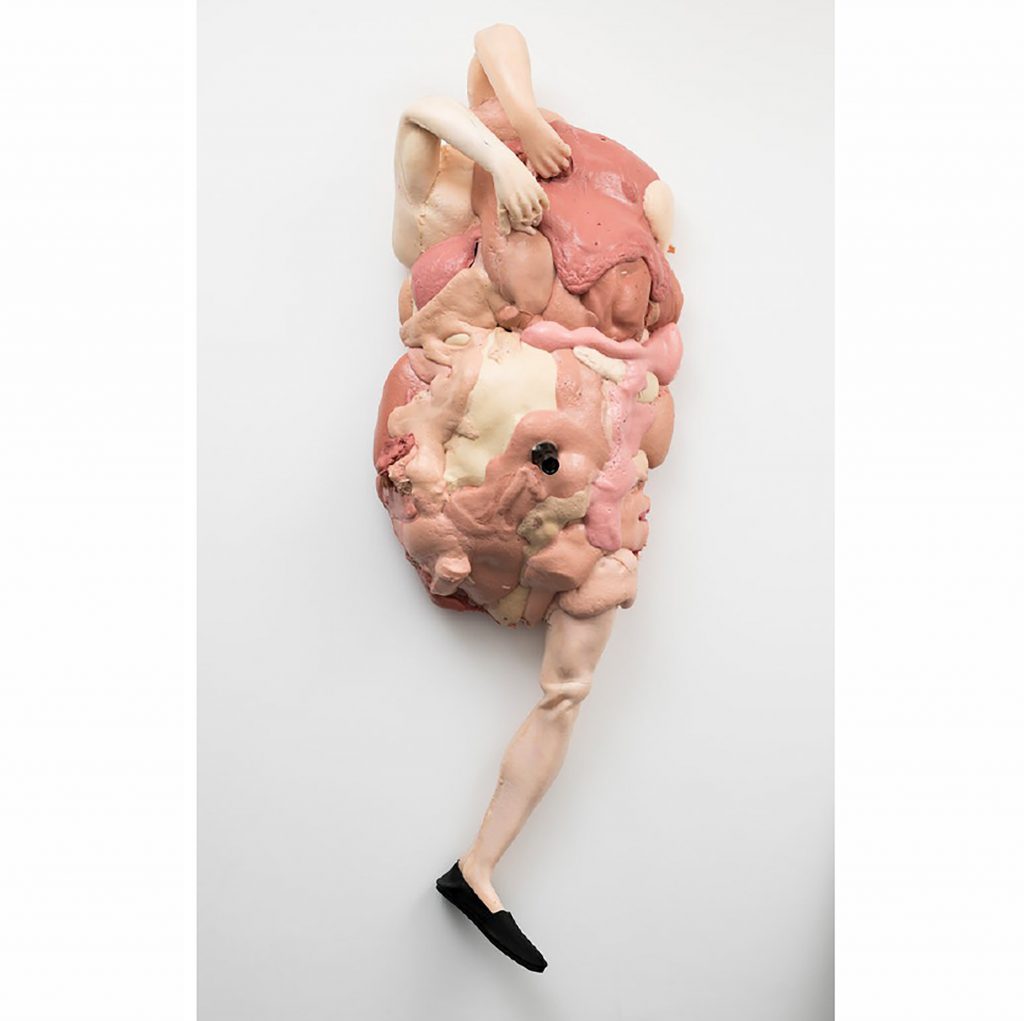

Fig. 4. Diego Bianchi, Alpargata, 2019

Often these bodies with which Bianchi works are not included in the narratives of political history or art theory, and if they are allowed there it is only because of their radical component. To overcome mechanisms of exclusion and re-coding, new practices and new sets of concepts are needed. It often seems that Diego Bianchi’s work is to analyze the political unconscious of history through its corporealities and fill the places and voids to reoccupy them in a fragmented movement of superimposition of material values (status, economy, beauty, etc…) and moral values (sexuality, ideological parties, states, even art schools and trends). Which allows him to oppose the integral lines of power with a performative network of transversal trajectories that go from object to action, and that enable a space for us to transit from the microphysics of power to the microphysics of resistance.

Fig. 5. Diego Bianchi, Blocking Me, 2019

As we know, there are regimes of visibility everywhere and in all aspects of our lives. When we talk about politics of appearance, we are saying that a group of people can be there, but they cannot appear to that society. The structure of society is coded against their appearance, they are “dark objects and bodies,” as Judith Butler would say, beings that are there but do not appear. Or rather, they do not appear as what they are, but as what they are not. They are coded as the negative of society, as that which should not be there, as that which does not belong. In this sense, politics is, in part, a politics of appearance. It is a struggle over who and what can appear. Are those that exist simply obscure objects, or will they become rebellious objects capable of transforming the social order? Will the regime of appearance be transformed through the appearance of the part that is not visible, redrawing the lines of the apparent and the inapparent? These bodies that Bianchi exposes and rehearses with are in front of us fighting and producing their own appearance. Will this movement be a line in the sand of the beach, condemned to be erased by the next wave, or will it leave a more lasting trace that affects the waves themselves?

Fig. 6. Diego Bianchi, Dedo, 2019

Bianchi’s work seems to tell us that all models that humanize and even romanticize the idea of collective and visibility can only work with the participation of the institutions of power, which requires the change of the collective consciousness into structures, external existences; in this case, politics will be identical to theology. The sculpture-bodies represented in the video Inflation have no State, no God and, therefore, no faith in one or the other: there is only existence. They are immersed in the automatism of their own survival, as they are excluded from another institutional and economic model of immersion: faith in the Big Other: in the personality of the sovereign, in the State, in God. It is powerful to see how in their displacement, sexuality and materiality intertwine to form something that is both physical and symbolic.

The political experience based on a materialization of collective bodies has something of a speculative and disposable game, but exposes without metaphor the social confrontations that fracture any easily assimilated image of identity. They are works and bodies that do not appeal to totality, but nevertheless make us feel degrees of freedom in their mere appearance and connections that evoke feelings and forms of symbiosis beyond the laws and binary ideological frameworks of left and right. Opening the body to other corporealities is a way of inhabiting the world and growing together. An arm that can have multiple extremities that disperse into many orifices that lead us to multiple other mouths also leads us to multiple senses. If the social exists as a fluid that frames and delimits the symbolic orders of what is visible and what is not, Diego Bianchi’s work is always escaping, shying away and putting a drop of uncertainty so that the semiotic machinery does not achieve its task of categorization and museification.

The work of the artwork is a work of making apparent, of making what is inapparent visible. The artwork is a sort of strange conceptualization that precedes everything true, letting appear what does not seem. There is never a simple glance or an innocent visibility, but always an apparatus that makes visible something that otherwise would not appear.