1. Pop art and its influence in Latin America

Although abstract expressionism was the movement that placed American art at the center of international debate, it was not until the emergence of pop art that it became a relevant point of reference for art debates in Latin America. This artistic movement emerged in the mid-20th century in Anglo-Saxon circles—first in the United Kingdom and later in the United States—as a visual language whose dynamics came directly from the patterns established by the production models of those mass consumer societies. Thus, using industrial techniques and materials, its artists optimistically assimilated images from mass culture into art spaces, offering direct and impersonal messages, in opposition to the abstraction and/or gesturality of the plastic languages that preceded them.

Instead of designating a cohesive group of artists with self-defined objectives in a manifesto, pop art encompassed a spectrum of disparate practices, unified only later by the critical eye. For this reason, dating the beginning of its production is a matter of debate. Today, historians agree that the Independent Group (IG) was the precursor to this movement. This interdisciplinary group, which originated at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London, held its first meeting in April 1952. On that occasion, British artist Eduardo Paolozzi gave a lecture in which he projected a large collection of images from magazines, postcards, and/or advertisements, which he had already been using as input in his work, almost as a prediction of the prominence that this resource would have in the subsequent imprint for which pop art would be internationally recognized.

Although it is the American branch of this movement that enjoys the widest international recognition, thanks to artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg, who in 1964 became the first American to win the grand prize for painting at the 32nd Venice Biennale. Its gestation in England is a fact that highlights the central role that the global assimilation of images from American mass culture played in these productions. In this regard, British architect Peter Smithson, a member of the IG, recalls:

The influence of American advertising has been interpreted as meaning that its appeal in the 1950s stemmed from the fact that it represented a level of luxury, given the relative deprivation imposed by the war. Here [in the UK], rationing did not end until the 1950s. […] So there was not the feeling that one has now that our world generally basks in abundance. There was a sense of how wonderful it was that somewhere you could have access to so many things1Peter Smithson. “Amigos del futuro: Una conversación con Peter Smithson”, in Doble exposición. Arquitectura a través del arte, ed. by Beatriz Colomina. (Akal, 2006), 95..

The ostentatious display of abundance in the face of scarcity was perhaps one of the most sophisticated strategies used by the United States in the context of the Cold War. In the face of global hardship, the American power presented itself as a savior, offering every conceivable novelty and implementing economic patronage programs for Europe and Latin America: the Marshall Plan (1948-1952) and the Alliance for Progress (1961-1970), respectively. It was in this context that images of American mass culture began to circulate in the West and enter the art world. Thus, it is not surprising that, both in England—the largest beneficiary of the Marshall Plan—and in Germany—the symbolic center of the brutal dispute over international influence in the postwar period—as well as in Latin America—a territory of violent imposition of the neoliberal model via military dictatorships— the images and concepts of pop art sparked intense debates, came into conflict with local interpretations of what was popular, and generated diverse scenes of artistic reception.

During the 1960s, Anglo-Saxon pop art works were exhibited and their concepts discussed in different Latin American cities. Buenos Aires and São Paulo were paradigmatic scenes of this. On the eve of military dictatorships that would disrupt the industrialization programs promoted since the postwar period by nationalist and reformist governments—those of José Domingo Perón in Argentina and Getulio Vargas in Brazil—both cities hosted major exhibitions sponsored by U.S. public institutions in partnership with local institutions that sought to spread the strident language of American pop art.

On the Buenos Aires scene, the cosmopolitan Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (ITDT) played a key role in all this. Since its inception in 1962, the International Prize awarded by this institution consistently received submissions from Anglo-Saxon pop artists21962: Eduardo Paolozzi; 1963: Ronald Kitaj, 1964: Robert Rauschenberg, Joe Tilsson and Jaspers Johns; 1965: Jim Dine, Allen Jones and James Rosenquist (the latter would win that year’s award); 1967: Allan D’Arcangelo. Similarly, in 1966, the year in which the international category was suspended due to lack of funds, British art critic Lawrence Alloway, a member of the IG who is credited with coining the term pop art, served as a judge for the national category of the competition., whose works, once evaluated by the jury, were exhibited to the public in Buenos Aires. A major effort would come in 1966, the year in which the award was suspended due to lack of resources. With the support of the American tobacco company Philip Morris International and the Cultural Service of the United States Embassy in Buenos Aires, the exhibition “Eleven Pop Artists: The New Image,” which presented thirty-two works by twelve artists linked to this movement3The participating artists were Allan D’Arcangelo, Jim Dine, Allen Jones, Gerald Laing, Roy Lichtenstein, Peter Phillips, Mel Ramos, James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, John Wesley, and Tom Wesselmann. ; an initiative that followed the opening of a solo exhibition by artist Andy Warhol at the Rubbers Gallery the previous year4The exhibition was titled “Andy Warhol” and was open between July 29 and August 14, 1965..

Meanwhile, on the São Paulo scene, the IX São Paulo Art Biennial held in 1967 is considered by some to be a triumphant moment for American pop art. As Marcelo Mari points out, “the impact and warm reception by most Brazilian critics of the United States pavilion [organized by the Smithsonian Institution and curated by William C. Seitz, associate curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA] speaks volumes about the central position occupied by this country as a beacon for new trends in world art.”5Marcelo Mari, «Arte pop, arte conceptual y el golpe militar en Brasil (1964-1970)», Estudios sobre las culturas contemporáneas (2022): 24 (48), p. 92. This pavilion featured two exhibitions: a retrospective of the realist painter Edward Hopper, who died just months after its opening; and a collective exhibition entitled “Ambiente U.S.A.: 1957-1967,” which presented a broad overview of American production over the last ten years through the exhibition of twenty-one artists and forty-five works in the gallery, where pop art played a leading role. Names such as D’Arcangelo, Indiana, Lichtenstein, Segal, Rauschemberg, Rosenquist, Warhol, Wesselman, among others, were present, as well as Jasper Johns, who received one of the awards at the event.

2. On the reception of pop in Chilean art circles

Unlike the cases described above, Santiago, Chile, in the 1960s was not the scene of major exhibitions of Anglo-Saxon pop art. In fact, it was not until 1985 that an exhibition by a renowned artist of this style was held in the Chilean capital6I am referring to the Robert Rauschenberg exhibition, which took place between July 17 and August 18, 1985, at the National Museum of Fine Arts. For a documentary study of the exhibition, see: Camila Estrella. Tu pregunta es mi respuesta. ROCI: Derivaciones de la visita de Robert Rauschenberg en Chile. (Ediciones Departamento de Artes Visuales UCh, 2024).. Thus, the reception of pop art in the country was initially mediated by debates in the media, where correspondents shared their impressions of international events. A similar function was fulfilled by the south-north training trips made by young artists, who became interested in the ideas linked to the movement and discussed them in their own productions upon returning to Chile.

«Escándalo en Venecia» (Scandal in Venice) read the headlines in large letters in the pages of the Chilean biweekly Ercilla a month after the close of the 32nd edition of the famous Art Biennale in the Italian city (1964). With this headline, Chilean researcher and cultural manager Tomás Lago, sent by the University of Chile as a correspondent, presented his review of the event:

What has happened? In short, the Americans, with all the weight of a well-resourced organization behind them, have set out to occupy the main space at the biennial, highlighting their artists and proposing an open break with the rest of the exhibition, for which they have even established a thesis of principle, which in this case has been called pop art.7Tomás Lago, «Escándalo en Venecia», Revista Ercilla no. 1534, 1964, 12-13..

Beneath the headline was a black-and-white reproduction of Buffalo II, the work with which Robert Rauschenberg had dethroned the School of Paris, and with it the European canon, in one of the most internationally visible spaces for artistic recognition. In this monumental canvas, an eclectic collection of images from American mass culture came together through screen printing. Comments such as “it’s nothing more than backward Dadaism” or “it has nothing to do with art” were widespread, as part of the impressions reported by Lago.

The following year, in a similar vein, Jorge Elliott, then director of the Institute of Plastic Arts Extension (IEAP) at the University of Chile, commented in El Mercurio on his visit to the 8th São Paulo Art Biennial: “Pop artists dazzle experts by hanging paintings that are signs. [He then lamented:] We are in the world of ‘anti-art’ and ‘anti-culture’; everything bores us and that is why we suffer from a real thirst for novelty and sensations.”8Jorge Elliott, «La bienal de São Paulo», El Mercurio, 30 de octubre de 1965, 5..

That same year (1965), in Santiago, another headline in Ercilla stated: “Pop art made its debut at the park fair.” It was referring to the 7th Plastic Arts Fair in Forest Park, which featured 750 stalls spread out between Pío Nono and Loreto streets, attracting an expectant crowd. There, “the laughter and openly ironic comments of the public were won over by the group Los Diablos, led by Francisco Brugnoli, professor at the School of Fine Arts, with their ‘pop’ paintings, in the latest fashion from Paris, London, and New York.”9José Pablo López, «El arte pop hizo su estreno», Revista Ercilla no.1592,1965, 11.. Faced with his proposals, other exhibitors, horrified, signed a letter asking the organizers to censor them, which ended with the dismantling of two pieces. Thus, amid controversy, disqualifications, and censorship, pop art made its entrance into the capital.

Chilean curator Soledad García has pointed out that, in line with the concerns we have just reviewed, “pigeonholed as second-hand art, Pop art in Chile was perceived as a foreign usurpation with no right to exist.”10Soledad García Saavedra. «Furia pop. Recepción crítica y exploraciones de un imaginario popular en el arte de los años sesenta en Chile», Inmaterial. Diseño, Arte y Sociedad. 4, No.7 (2019): 55, https://doi.org/10.46516/inmaterial.v4.56. The practices of artists who, through direct messages and materials from mass consumer culture, linked the languages of pop art with the imaginaries of the popular and the political in Chile during the 1960s are now marginalized. Taking the work of Francisco Brugnoli, Valentina Cruz, Virginia Errázuriz, and Guillermo Núñez as case studies, García attributes this situation to two reasons: first, the defense by specialized critics of the 1960s of the canon of European modern art, which viewed the emergence of this new North American language with suspicion (a thesis verifiable in the comments by Lago and Elliott referenced above); and second, to the violent rupture caused by the 1973 coup d’état and subsequent dictatorship in the national art scene, which would end up casting a cloak of oblivion over the practices that had been developing up to that point:

The power of that discourse and of artistic practices after 1973 left a legacy in artistic and historiographical training from the 1990s to the present day, leading to the oblivion of those conventions and revolts that exalted the artistic and social conflicts of the long decade of the 1960s (1960-1973) with color and direct messages. Covered by a historical tabula rasa, one could conjecture that there was rejection and discomfort in addressing and reopening those old discussions that were shattered by the coup.11García, «Furia pop», 58..

Despite the above, the truth is that pop art did not cease to be relevant after 1973. As the escalation of events that led to Chile’s institutional breakdown unfolded, artists who had traveled abroad returned loaded with references, including pop art, which they would later use in the development of their works. Thus, notable productions from the post-coup period incorporate strategies that refer to this style. To cite a few examples, Roy Lichtenstein’s treatment of the American comic book image in his paintings was crucial to the development of Eugenio Dittborn’s practice, who returned in 1972 from a four-year training trip to Europe. Regarding this experience, the artist has stated: “[During my stay] I saw an exhibition by Lichtenstein—the first Lichtenstein I had ever seen—and that was absolutely decisive for me.”12Centro para las Humanidades UDP. «La ciudad en llamas – Eugenio Dittborn (Primera Parte)». Vídeo de Youtube, 03:31. 31 de marzo de 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0akngGYD8q4. And then he specifies: “it determined my entire subsequent search.”13Centro para las Humanidades UDP, «La ciudad en llamas – Eugenio Dittborn (Primera Parte)», 05:23.. Along the same lines, the use of newspapers as raw material by British pop artists was central to the development of Catalina Parra’s collage work. In 1969, while living in Germany, she visited an exhibition entitled “Information: Tilson, Phillips, Jones, Paolozzi, Kitaj, Hamilton” at the Kunsthalle Basel (Switzerland). Through sixty-six works, this exhibition offered an overview of the latest metropolitan art movement in full bloom. In the artist’s words: “There were works by Paolozzi, Kitaj, Hamilton, among others, and I realized that they worked with elements of everyday life, and that had a big impact on me. From that moment on, that way of working had a great influence on my work”14Catalina Parra. «Contextualizándonos: Una conversación para comenzar». In Catalina Parra. El fantasma político del arte, ed. Paulina Varas Metales Pesados. 2011), 20.. The poet Ronald Kay made a similar point: “Knowledge of Pop was very important to me, […] Hamilton, for example, has a piece full of references to newspapers. Likewise, I re-enact some things in Variaciones [Ornamentales]»15Ronald Kay. «La imágen, una pasión. Conversación entre Ronald Kay y Bruno Cuneo», in Paisajes espectrales: Tentativas sobre Ronald Kay, ed. Andrés Soto & Francisco Vega (Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2019), 192..

Thus, as an isthmus between two radically divided moments in Chilean art, pop art appears to us as a shared interest among generations of artists who remained active before and after the coup, nuancing discourses that speak of a disconnect between these two scenes. These discourses have linked pre-coup practices to the influence of pop art and post-coup practices to that of conceptual art, but the truth is that the trajectories of the reception of these artistic movements were not so clear-cut. Among the post-1973 practices that revisited the lessons of pop art, it is perhaps that of Gonzalo Díaz that deserves a separate section for analysis.

3. Pop strategies in Gonzalo Díaz’s painting

The exercise of using pop art as a category to designate works produced in Latin America remains problematic. British art critic Lawrence Alloway, a member of the IG and credited with coining the concept, noted: “[with Pop Art] I tried to define the ‘popular arts of our industrial civilization’ on the basis of their acceptance. The new role of the Fine Arts will be one of the possible forms of communication within a broader framework that also includes the mass media.”16Lawrence Alloway. «El desarrollo del pop art británico», in El Pop Art, ed. Lucy Lippard (Ediciones Destino, 1993), 36.. Here, the notion of the popular relates specifically to the mass production and consumption characteristic of industrial societies, whose “popular” images and materials—insofar as they are accessible to anyone—would, upon entering the world of art, bridge the gap between art and everyday life, thus constituting a democratizing exercise. Now, is it possible to use this category in territories where socioeconomic modernity was far from the norm?

According to Argentine thinker Néstor García Canclini, “cultural modernism does not express economic modernity [but rather, to paraphrase English historian Perry Anderson, occurs at] the intersection of different historical temporalities.”17Néstor García Canclini. Culturas Híbridas. Estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad. (Grijalbo, 1989), 70.. While in Europe this crossover encompassed the advanced artistic academicism prior to the First World War, the technological innovations brought about by the Second Industrial Revolution, and the social revolution crystallized in the Russian Revolution, in Latin America this process involved indigenous traditions, colonial Catholic Hispanicism, and certain modernizing actions in the political, educational, and communicational spheres. “Despite attempts to give elite culture a modern profile, confining indigenous and colonial elements to popular sectors, interclass mixing has generated hybrid formations in all social strata.”18García Canclini, Culturas Híbridas, 71., dice García Canclini.

Thus, the homogeneity of modernity in the north contrasts with the hybrid nature of modernity in the south, where the adjective popular will be used to relegate and classify certain cultural practices as pre-modern, traditional, or artisanal, that is, the antithesis of what the abbreviation pop is intended to designate. In short, “in this story, the popular is the excluded”19García Canclini, Culturas Híbridas, 191.; not what is accessible to all. Therefore, its implementation in places where the logic of mass production and consumption is far from the norm raises the following question: how can we preserve the critical vocation of pop art, which sought to bring art closer to everyday life?

In recent years, a sustained interest in studying the scope of pop art beyond the Anglo-Saxon axis in which it originated has been expressed in the efforts of various anthological exhibitions that have focused on the global dimension of this artistic language, presenting works produced outside the traditional metropolitan centers20To mention a few: in 2012, curated by Rodrigo Alonso and Paulo Herkenhoff, the exhibition “Arte de contradicciones. Pop, realismos y política. Brasil – Argentina 1960” opened at Fundación Proa in Buenos Aires. In 2016, curated by Soledad García, “Pop crítico. Colección MSSA” was held at the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile. That same year, curated by Jessica Morgan, Flavia Frigeri, and Elsa Coustou, “The World Goes Pop” opened at the Tate Modern Gallery in London and “International Pop,” curated by Alexander Darsie and Ryan Bartholomew, opened at the Walker Art Center in Minnesota. In 2018, “Pop America 1965-1975,” curated by Esther Gabara, was held at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. In 2025, “Pop Brazil: Avant-garde and New Figuration, 1960-70,” curated by Pollyana Quintella and Yuri Quevedo, was held at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo. All of these exhibitions feature works from a wide variety of latitudes, supporting the thesis of pop art as a global language.. Among them, curator Esther Gabara’s21Esther Gabara, Pop América 1965-1967. Durham: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2019. proposal points us in an interesting direction, inviting us to think of this category not as a specific concept for dating an innovation in art history—pop as a noun—but as a set of strategies available for reflecting on the global expansion of the dynamics of mass production and consumption—pop as a verb. This opens up a neo-pop horizon, capable of being used by artists in various contexts to account for their own unique experience of receiving mass culture.

This is a fertile perspective for understanding the institutional criticism deployed in Gonzalo Díaz’s works from the period 1982-1987, which constitute a particular unit of analysis within the artist’s vast body of work and are characterized by challenging the tradition of painting as bourgeois through the implementation of languages close to pop art, among which the following stand out: the revaluation of serialization, the use of synthetic pigments and strident colors, a predilection for realistic representation after an education that favored abstraction, and, in particular, an interest in the iconography of mass-produced and domestically manufactured consumer products as a way of bridging the gap between high and low culture. These works have been classified by local historiography as part of the national art neo-avant-garde, arousing widespread interest. So, it is worth asking ourselves: what role, if any, did pop art play in Díaz’s strategy to earn a place in the annals of the local avant-garde, whose narrative was argued to be radically critical of the craft of painting?

Upon returning from the traditional transatlantic educational trip that took him to live for a year in the Italian city of Florence, Gonzalo Díaz was steeped in the debates that were taking place in Europe around the revision of the legacy of the Historical Avant-Gardes. His perception of the tone these conversations took on in the Italian scene in particular was recorded in an interview with him by the director of the National Museum of Fine Arts, Nena Ossa, in 1982, published in the newspaper La Nación just months after his return:

The most important thing about the transavantgarde is that it breaks with the traditional evolution of the avant-garde. Bonito Oliva calls this tradition the Darwinian evolution of the avant-garde, because one derives from the other, rendering the previous one obsolete and creating an intolerance that transavantgarde artists do not have. If they want to paint flowers, they paint flowers. If they want to paint abstractly, they paint abstractly; there are no restrictions. But in general, they follow a trend: they put everything at the service of subjective hyper-expression; they are expressionists without measure.22Gonzalo Díaz, interview with Nena Ossa, «Reportaje de arte: Gonzalo Díaz habla sobre el arte italiano cultural», La Nación, 7 de abril de 1982.

Díaz’s words indicate that the teleological nature of modern art history, which made painting increasingly intolerable—to use his own term—was being thoroughly questioned. Although the expressionist vocation of the Italian Transavantgarde, which advocated for the autonomy of art, was far removed from the artist’s interests, this movement showed him a panorama in which painting regained a certain relevance and was capable of coexisting with practices that went beyond the framework toward experimentalism. This was stimulating for a painter situated in the Santiago art scene, where a narrative was beginning to take shape based on avant-garde practices that incorporated the city and/or the body as a medium for art, to the detriment of painting23See Nelly Richard. Márgenes e instituciones. Arte en Chile desde 1973. (Metales Pesados, 2014)..

It was at this transatlantic crossroads that Díaz began to forge a proposal that had painting as its object and graphic art as its instrument. Next, we will review the implementation of this critical strategy in the three works where the artist used advertising iconography as a leading resource: Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (1982), Let me see if you can run as fast as me (1984) and the series Marcación del territorio (1986-1987).

3.1 Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (1982)

The introduction of a new way of thinking about the iconography of mass consumer products in Gonzalo Díaz’s work had its inaugural moment in the iconic exhibition “Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena” (A Sentimental History of Chilean Painting), which opened on July 17, 1982, at Galería Sur, shortly after the artist’s return to Santiago. In this exhibition, the illustration that forms part of the logo of the Chilean detergent brand Klenzo—a woman dressed in traditional Dutch costume and holding a box of the product in her right hand—was proposed as a Madonna of national painting and reproduced repeatedly along the entire length of a paper strip that hung at eye level ran along the perimeter of the gallery walls. At the foot of this visual narrative was a text that attempted an ode to this particular Chilean Madonna with a bonnet. It read: “In your outline of loss I set my eyes to raise you to the lyrical summit and the high thrones of history written by the painter. You are loss. I too could love you.”

A peculiar account by Gonzalo Díaz about his stay in Italy illustrates the origin of this work:

While I was there, I devoted myself to painting and painting. I had brought a container of Klenzo with me, which I carried in a small folder containing my entire archive of images and projects. I had it pinned up in my studio in Florence. […] I hadn’t done anything with it yet, but those images were there. It was my way of having a reference to where I came from, because I was Chilean, I came from the Chilean military desert, and I was there, weightless, immersed in a very strange vacation, so far away…24Gonzalo Díaz, interview published in Filtraciones I. Conversaciones sobre arte en Chile (de los años 60’s a los 80’s), ed. Federico Galende (Editorial ARCIS / Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2007). p.170

Fig. 1. Gonzalo Díaz, Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (1982). Paper, synthetic enamel, silkscreen, neon, various objects (feather duster, pencil, wooden toy, plumb bob, level © Photographs: Víctor Hugo Codocedo

In the scene described by Díaz, the product of national industry seems to be a catalyst for that singular form of nostalgia that overwhelms the outsider, becoming a profane standard of the homeland, whose triviality allows the institutional character with which these devices, driven by the force of the state, construct the national identity to be ironically obliterated. Díaz’s critique of the institutionality of painting through graphics will always end up leading to a reflection on the homeland, and with it, on politics, where painting has always played a strategic role.

From this point of view, it is particularly interesting to note two small installations that brought Klenzo into contact with national iconography in Díaz’s exhibition at Galería Sur: the first, a heart-shaped pin cushion in the colors of the national flag displayed on a colorful stool leaning against the wall and under a poster entitled “National Sculpture Competition”; and the second, a wooden structure bearing the words “national song of painting ch” and from which hang, by means of tricolor ribbons, five small bags with unidentified contents. The link between the national and the pictorial is made explicit here through allusions to different instances of artistic recognition and/or consecration. The national anthem, the national competition, the national registry of critics, the national honorable mention award, and the tricolor flag are all elements that point to the use of painting as an instrument for constructing the patriotic, enabling the introduction of the political into this critical strategy.

Fig. 2. Gonzalo Díaz, Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (1982). Wooden easel, tricolor ribbon, plastic bags. © Photographs: Víctor Hugo Codocedo

Fig. 3. Gonzalo Díaz, Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (1982). Silkscreen print on paper, neon, stool, pin cushion, photocopy. © Photographs: Víctor Hugo Codocedo

3.2 Let me see if you can run as fast as me (1984)

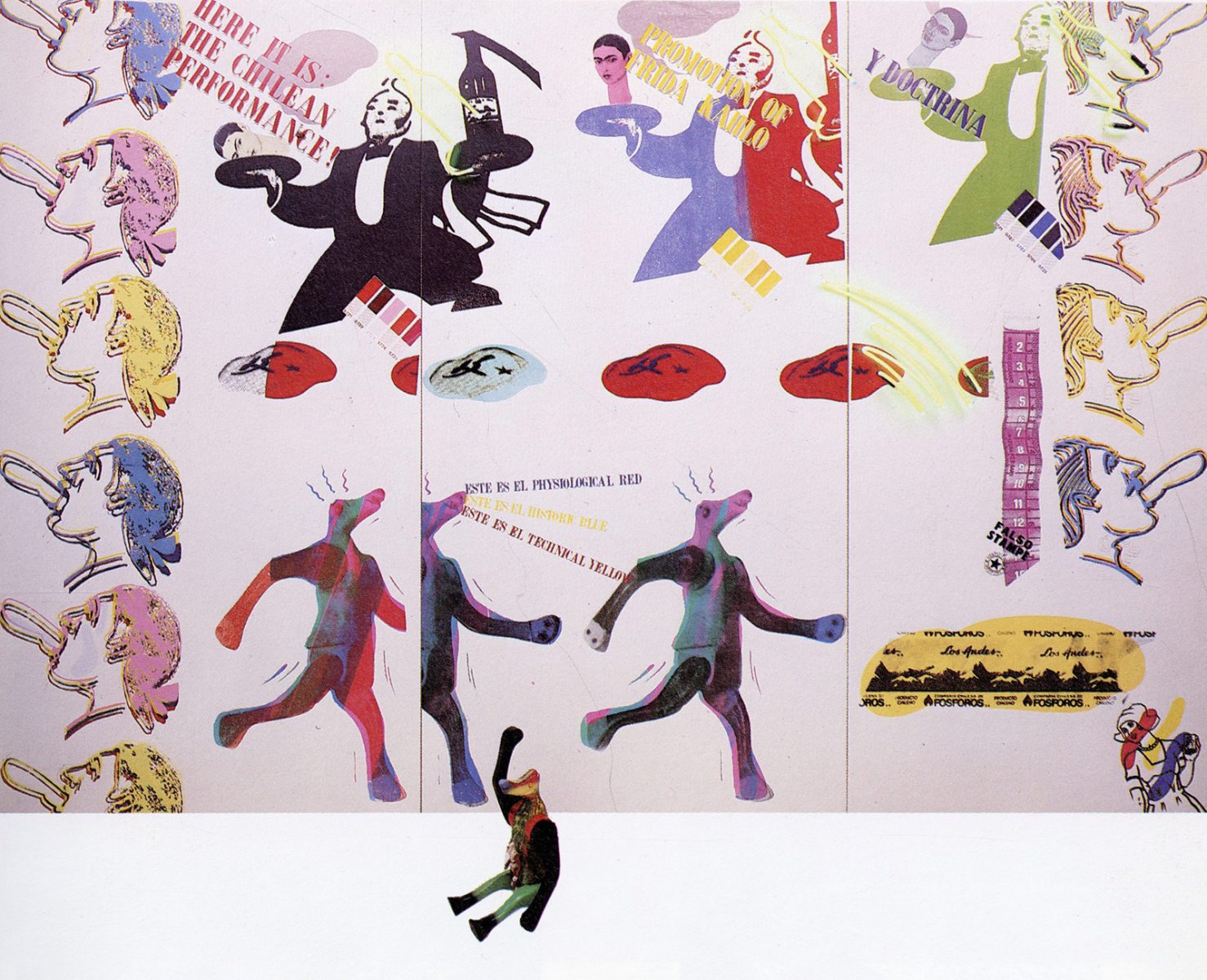

Regarding the links between the patriotic, the political, and the pictorial that emerge in Díaz’s critical strategy, it is interesting to note that much of the implementation of this strategy took place internationally. This can be seen when analyzing the work Let me see if you can run as fast as me (1984), which represented Chile at the 5th Sydney Biennial in Australia, alongside works by Eugenio Dittborn and Juan Domingo Dávila. There, Klenzo’s iconography was joined by that of the Chilean match company Los Andes and the Santa Carolina winery. Thus, in this triptych of monumental dimensions, an eclectic set of icons printed using silkscreen was presented in a vibrant palette of colors, among which stood out that of a waiter dressed in a tailcoat, an icon of Viña Santa Carolina, who runs in a helpful manner to offer Chilean wine—a distinguished national export delicacy—on a tray, and next to him, by the artist’s own hand, the head of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, an icon and stereotype of Latin American art 25Towards the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s, Frida Kahlo’s status as a pop icon was consolidated. In addition to her first biographies published in Mexico (Del Conde, 1976; Tibol, 1977), 1982 saw the first international retrospective exhibition of her work, Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti. Opened at the prestigious Whitechapel Gallery in London, it was curated by British filmmakers Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, and later traveled to Germany, Sweden, Mexico, and the United States. This coincided with the publication of her first biography in English (Herrera, 1983). “In the early 1980s […] a wave of enthusiasm generated by the rediscovery of her person, her charismatic personality, and her political activism […] genuine admiration that eventually faded over time in light of the commercialism to which the stereotype was subjected, produced and falsely promoted by artistic centers such as New York; She came to represent the artistic image of an entire continent,“ Mari Carmen Ramírez in ”Cómo se yergue el ícono Frida” [How the Frida Icon Rises] [conference], Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires, September 21, 2022.. All this was offered to a hungry international audience. The waiter reproduced on each of the triptych panels was accompanied by the following captions (two of them in English, as was the title of the work): “Here it is: a Chilean performance!”, “promotion a Frida Kahlo,” “y doctrina.”

Fig. 4. Gonzalo Díaz, Let me see if you can run as fast as me (1984). Silkscreen and stencil on canvas, neon, wooden toy 270 x 400 cm. Source: 5th Sydney Biennial, exhibition catalog.

Overflowing with acid irony and referencing the brand’s slogan (“drink Santa Carolina out of conviction and doctrine”), Díaz once again constructs a representation of national and now also regional art through the iconicity of consumption. Although this time the object of his criticism seems to be contemporary practices, “Chilean performance,” the reference to his previous imagery, an exercise that privileges practice over the work, draws a line of sustained debate. In the words of art critic Justo Pastor Mellado: “The iconographic background of Chilean advertising […] allows us to anchor the reference that founded them in order to remember in yesterday’s Madonna the model to be restored […]. That is, Carrerianos and O’Higginistas in the republican dispute of the pictorial authorities.”26Justo Pastor Mellado, «Cuestión de etiqueta», in Envío a la 5ª Bienal de Sydney. Arte & Textos [No.11], ed. Gonzalo Díaz, Eugenio Dittborn, Nelly Richard, Justo Mellado, Adriana Valdes, Gonzalo Muñoz (Galería Sur, 1983)..

3.3 Marcación del territorio (1986-1987)

The peak of this strategy linking painting, graphic art, and the notion of homeland came in 1987, when the artist received a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, which enabled him to develop the project “Marcación del territorio o introducción al paisaje chileno” (Marking the Territory or Introduction to the Chilean Landscape), resulting in a series of works that continued along the lines of the two works we have just reviewed. The first of these works, entitled Para escribir en el cielo (To Write in the Sky), appears dated one year before the award of the grant in certain publications27See Gaspar Galaz y Milan Ivelic, Chile Arte Actual, (Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, 1988) and VV.AA. Chile Vive. Muestra de Arte y Cultura (Círculo de Bellas Artes, 1987)., however, it was not until 1987, with the piece Marcación del territorio (Marking the Territory), that the arguments of Díaz’s project were fully developed. This work marked the artist’s participation in the exhibition Chile Vive (Chile Lives), an exhibition organized on the initiative of a number of institutions in Spain, which was celebrating fourteen years since its return to democracy after three decades of Francoism. The exhibition took place at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, seeking to give international visibility to Chilean cultural production on the eve of the transitional process that was looming on the horizon, as stipulated by the 1980 Constitution.

Fig. 5. Gonzalo Díaz, Marcación del Territorio (1987). Oil, latex on canvas and wood, 300 x 460 cm. Source: Gonzalo Díaz Archive

Díaz’s work consisted of two panels, each subdivided into three parts: the first two depicted scenes from the Chilean landscape—the sea and mountains—using oil on canvas and figurative language, with the horizon line and vanishing points drawn on them; in the remaining third, the usual iconography of consumer products cited by the artist appeared—the Klenzo girl and the Viña Santa Carolina waiter—whose synthetic graphic language was captured through the uniformity of latex on wood, a firm material that allowed them to break the orthogonality of the frame. In short, the work constituted a careful play of contrasts between techniques (oil/latex), supports (canvas/wood), and visual (painting/graphics) and chromatic languages. While on one panel the seascape was represented in black and white, the adjacent iconography was in color. On the other panel, it was the reverse.

Two phrases crossed the sky longitudinally in the scenes on each panel: “there is a body here that succumbs” crossed the coastal sky and “mother, this is not paradise” crossed the mountainous sky. Although the exact origin of these quotes is unknown, they can be attributed to two events that aroused great public interest in Chilean society at different moments in its history and to which Díaz referred in a document accompanying his work: the beheading of Zulema Morandé in 1914 and the beatification of Sister Teresa of the Andes in 1987. While the perpetrator of the sadistic murder at the beginning of the century escaped punishment in a spurious trial, a process of sanctification began at a time when the most heinous sins were committed as state policy: corruption and camouflage. Díaz referred to these events as “two criminal cases of the Republic invested as thematic procedures in the investigation of social marks”28Gonzalo Díaz, Escritos 1980-2020 y Textos en Obra (Metales Pesados, 2025), 35..

The notion of social branding is articulated with that of graphic branding in Díaz’s work in a particular way. On the other hand, we must pay attention to the marks relating to the language of visual composition (horizon line and vanishing points), as well as the intricate metaphor contained in the cattle tracks imprinted there, a reference to the myth of the birth of Hermes, who, when stealing his brother Apollo’s cattle, devises various strategies to hide the tracks of the cattle, the evidence of the crime. Social marks and graphic marks thus outline a paradox: “Strategists seek to make what is directly visible invisible,” Díaz points out, adding: “the painter wonders how to make visible what remains hidden from view”29Gonzalo Díaz, Escritos 1980-2020 y Textos en Obra..

This careful game of hide-and-seek and revelations portrayed the Chilean landscape, narrowing the gap between the artistic and the political. In this regard, Díaz stated: “Only painting is capable of dismantling the dictatorship by marking the landscape. Only painting distances itself from the legal demarcation of the territory of the republic and dismantles the illustrativeness of all political discourse”30Gonzalo Díaz, interview with Luisa Ulibarri, «Un mozo antiguo, una rubia con gorrito y 24 mil dólares», La Época, 26 de julio de 1987, 25..

After its inauguration in Madrid, the exhibition “Chile Vive” was intended to travel to various European cities, starting with Barcelona, and then moving on to France and Italy. However, in the Catalan city, the exhibition underwent a process of editing and its journey was cut short, preventing it from continuing its tour. The piece Marcación de Territorio was also lost there.

4. Discrepancies and twists of pop art in the Latin American critical scene

Pop art was not a category that aroused the interest of local critics when considering the historical significance of Gonzalo Díaz’s works from the period 1982-1987, nor was it one to which the artist explicitly wished to pay tribute. Rather, it was a kind of ghost that haunted his works, the product of the proximity of languages and strategies. In reality, as we will see in this last section, pop art was a category that was argued against on different occasions in search of differentiation. The arguments put forward reveal a stance that spread among the artistic intelligentsia of different scenes in Latin America when this style arrived in the region.

For Díaz, this issue arose even before the period studied here, in his early years after graduating from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Chile, where he trained as a painter and was particularly influenced by the informalism of José Balmes and the late impressionism of Adolfo Couve (whose assistant he later became). Indeed, recalling this period, marked by the search for his own artistic language, the artist notes: “According to international correspondence, the usual thing would have been to try my hand at Pop Art. However, not only did it seem like an easy solution to me, but there was no basis for it in my intellectual training.”31Gonzalo Díaz, «Statement Marcación del Territorio», 1987, GD-D-00319, Archivo Gonzalo Díaz, 1.3, https://archivo.gonzalodiaz.cl/Detail/objects/2529. The fact is that committing to pop art in the early 1970s meant walking down a path that had already been paved: the style was already internationally established and was nothing new. On the other hand, Díaz notes that, as a result of the sociocultural process that Chile was undergoing at the time, there was also a kind of “rejection of American artists for being American […] it was sinful, especially pop art, […] it was imperialist.”32Gonzalo Díaz, interview with Camila Estrella published in Tu pregunta es mi respuesta. ROCI: Derivaciones de la visita de Robert Rauschenberg en Chile (Ediciones Departamento de Artes Visuales UCh, 2024): 95..

Later, however, in the 1980s, the same categories used to describe pop art works in the context of the somewhat disconcerting emergence of this movement, such as Dadaism—for its incorporation of heteronomous references into the self-sufficient logic of the art world—and realism —for its return to images of everyday life—were also used by critics to approach the use of consumer iconography in Díaz’s work. With regard to Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (Sentimental History of Chilean Painting, 1982), critics Gaspar Galaz and Milan Ivelic, for example, pointed out: “there is a conceptual mechanism analogous to the ready-made in the deconstruction of Klenzo detergent […] it defunctionalizes the image of its advertising purpose to make it a field of critical reflection on painting.”33Gaspar Galaz y Milan Ivelic, Chile Arte Actual (Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, 1988), 313.. For his part, and with regard to the 1987 exhibition “Artists Present Artists,” where Díaz exhibited the last piece in the series Marcación del territorio 34Exhibited in the show “Artists Present Artists,” which took place in May 1987 at the Plástica 3 gallery. The piece Hipo Tesis consisted of four panels, two central ones reproducing scenes from the national landscape, with the coastal landscape remaining and the mountain range replaced by a postcard of the desert, on which the prominent black cross and a color control strip from the opposite panel were printed. Above both panels, a glass panel supported by 16 metal pieces displays the neon words “hipo” and “tesis.” Each panel also features a concave space that holds two small frames displaying a silkscreen-printed ecphratic description of two traditional characters: the Klenzo girl and the Santa Carolina Vineyard worker., Justo Pastor Mellado states: “Not everything related to the advertising industry in the painting system is indebted to pop art”35Justo Pastor Mellado. «Meter la pata o presentación de la obra de Gonzalo Díaz en Chile Vive», Ediciones VISUALA, 1987), 3., adding: “Díaz’s commission aims to break the legitimacy of Catalan machismo in Chilean painting through parodic realism. Through a parody of realistic painting. Díaz’s move cannot be called hyperrealistic, but rather hyperparodic and, therefore, hyporealistic”36Justo Pastor Mellado. «Meter la pata o presentación de la obra de Gonzalo Díaz en Chile Vive», 28..

Alongside this commentary, cultural critic Nelly Richard’s argument was perhaps the one that most explicitly sought to twist pop’s theoretical assumptions and visual strategies in order to make a difference. Let’s take a look:

the introduction of the Klenzo reference as a support for pictorial revision in Gonzalo Díaz’s work is useful, in contrast [to American pop art], the representative discordance that means that those who use Klenzo see themselves as excluded from the discourse articulated by culture—seeing themselves denied by painting in the absence of correlates that legitimize them socially, seeing themselves expelled from the field of subjectivation that painting programs as official37Nelly Richard, «Reivindicación de la sentimentalidad como discurso», La Separata, No. 4 (1982): 1-2..

Thus, while Anglo-Saxon pop art understood the introduction of references from mass culture as a strategy that bridged the gap between high and low culture, Richard conceived the same operation in Díaz’s work in the opposite way, that is, as an exercise that made that distance explicit. The twisting and overflowing of art categories thus become a strategy for thinking about our uniqueness. “Refusing to be annexed in terms of cultural territoriality does not mean closing oneself off to foreign contributions by virtue of a presumed authenticity [, but rather being able to] evaluate those contributions in terms of our own historical convenience”38Nelly Richard, «Latin America: Cultures of repetition or cultures of difference? », en The fifth Biennale of Sydney. Private symbol: social metaphor, ed. por Leon Paroissien, (Biennale of Sydney, 1984), p. s/n., said Richard about the 1984 submission to the 5th Sydney Biennial, adding: ”We validate the construction of our own phrases with received vocabularies and syntax as a maximum critical strategy”39Ibidem. This was a phenomenon that, with regard to pop art, spread throughout the region, where critics proposed their own approaches and adjectives to think about the arrival of this language.

Brazilian art critic Mario Pedrosa, who understood pop art as an alienating mimesis of advertising dynamics, warned in 1967 that: “pop, in countries like ours, cannot have the same purpose”40Mario Pedrosa, «Do pop americano ao sertanejo Dias», in Mario Pedrosa: Acadêmicos e modernos 3, coord. Otília Arantes (Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1998), 368., marking from the outset a difference between a possible local practice and the Anglo-Saxon one. Colombian writer Marta Traba, expressing similar concerns, stated in 1974 that “in our dependent and underdeveloped economies, there is no such pressure from consumer society on the individual”41Marta Traba. Historia abierta del arte colombiano, (Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, 2016), 331-332., a fundamental argument of the movement. For his part, in 1967, Argentine critic Oscar Masotta approached pop from a much more optimistic perspective: “pop constitutes a radical critique of an aesthetic culture like ours”42Oscar Masotta. El «Pop-Art», (Editorial Columba, 1967), 19., capable of being undertaken from the various corners where the dynamics of mass consumption have been received (note how he uses the possessive pronoun “our” to designate a cultural horizon shared between North and South America). He then declares that “the plurality of meanings […] of American pop propositions was joined by the plurality of Argentine propositions”43Masotta. El «Pop-Art», 21..

After analyzing certain works by young artists who, in their own contexts, were interested in using visual codes learned from pop art, the aforementioned critics agree on the fundamental differences between the uniqueness of Latin American practices and the impersonal nature of Anglo-Saxon ones. Thus, Pedrosa points out that Antonio Dias and Rubens Gerchman “do not make things aimed at satisfying consumerism for consumerism’s sake. The difference between them, ‘pop artists’ of underdevelopment, is that they choose for whom to produce”44Pedrosa, «Do pop americano ao sertanejo Dias», 368.. In this regard, the author agrees with Masotta, who observes that Marta Minujin’s work, specifically her piece El Batacazo (1964), “largely responds to the pop principle of emphasizing material consciousness”45Oscar Masotta. Revolución en el arte. Pop art, happenings y arte de los medios en la década de los sesenta (Edhasa, 2004), 282. but attaches fundamental importance to personal experience, typical of happenings, constituting a departure from the metropolitan reference point in that it offers “a message whose recipient is everyone”46Masotta. Revolución en el arte, 283.. In this way, both authors distance themselves from the impersonal nature of the Anglo-Saxon style.

For his part, Traba will point out that Beatriz González and Bernardo Salcedo’s practice is capable of redirecting pop’s critical vocation toward an analysis of the “national absurd” in order to use “cruel jokes and sarcasm as escapism, managing to distinguish themselves from foreign models”47Traba. Historia abierta del arte colombiano, 332., by implementing a “located pop.” Along these same lines, we can understand Gonzalo Díaz’s strategy of challenging the bourgeois character of painting through consumer graphics, and the twist introduced by Richard to think of it as a counterpoint to the democratizing vocation of Anglo-Saxon pop, as a strategy that points out and denounces exclusion.

Thus, studying pop as a verb not only offers us a platform on which to visualize the uniqueness of Latin American practices in relation to a common foreign reference point, but also forces us to reconsider the canonization of Latin American conceptual art (or conceptualism). When considering the strategies that linked the poetic and the political in the art of the region in the second half of the 20th century, the democratizing vocation of pop art appears as a reference point that, apart from the tautological self-reflexivity of conceptualism, taught artists to narrow the distance between art and reality. Understanding the influence of movements such as this should not be naive and, rather than evaluating their correct implementation, should observe their misalignment and distortion. In this way, it is possible to open up an enriching critical space to influence the logic of knowledge circulation from the global south.

References

Alloway, Lawrence. «El desarrollo del pop art británico». En El Pop Art editado por Lucy Lippard, 27-68. Barcelona: Ediciones Destino, 1993.

Díaz, Gonzalo. Entrevista de Nena Ossa. «Reportaje de arte: Gonzalo Díaz habla sobre el arte italiano cultural». La Nación, 7 de abril de 1982, 2A.

Díaz, Gonzalo. Entrevista por Federico Galende. Filtraciones I: Conversaciones sobre arte en Chile (de los años 60’s a los 80’s). Santiago de Chile: Editorial ARCIS / Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2007.

Díaz, Gonzalo. «Statement Marcación del Territorio», 1987. Archivo Gonzalo Díaz, Santiago de Chile, GD-D-00319, p. 1.3, accedido el 27 de septiembre de 2025 https://archivo.gonzalodiaz.cl/Detail/objects/2529

Díaz, Gonzalo. Entrevista de Luisa Ulibarri. «Un mozo antiguo, una rubia con gorrito y 24 mil dólares». La Época, 26 de julio de 1987, 25.

Díaz, Gonzalo. Entrevista de Camila Estrella. «Entrevista a Gonzalo Díaz». En Tu pregunta es mi respuesta. ROCI: Derivaciones de la visita de Robert Rauschenberg en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Departamento de Artes Visuales UCh, 2024.

Díaz, Gonzalo. Escritos 1980-2020 y Textos en Obra. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2025.

Del Conde, Teresa. Vida de Frida Kahlo. Ciudad de México: Secretaría de la Presidencia, 1976.

Dittborn, Eugenio. Entrevista de Camilo Yañez. «La ciudad en llamas – Eugenio Dittborn (Primera Parte)», Vídeo de YouTube, 31 de marzo de 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0akngGYD8q4

Elliott, Jorge. «La bienal de São Paulo». El Mercurio, 1965, 5.

Estrella, Camila. Tu pregunta es mi respuesta. ROCI: Derivaciones de la visita de Robert Rauschenberg en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Departamento de Artes Visuales UCh, 2024

Gabara, Esther. Pop América 1965-1967. Durham: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2019.

Galaz, Gaspar e Ivelic, Milan. Chile Arte Actual. Valparaíso: Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, 1988.

García Canclini, Néstor. Culturas Híbridas. Estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad. Ciudad de México: Grijalbo, 1989.

García Saavedra, Soledad. «Furia pop. Recepción crítica y exploraciones de un imaginario popular en el arte de los años sesenta en Chile», Inmaterial. Diseño, Arte y Sociedad 4, no.7 (2019): 55 https://doi.org/10.46516/inmaterial.v4.56

Herrera, Hayden. Frída. A biography of Frida Kahlo. Nueva York: Harper & Row, 1983.

Kay, Ronald. Entrevista de Bruno Cuneo. «La imagen, una pasión. Conversación entre Ronald Kay y Bruno Cuneo». En Paisajes espectrales: Tentativas sobre Ronald Kay, editado por Andres Soto y Francisco Vega, 179-209. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2019.

Lago, Tomas. «Escándalo en Venecia». Revista Ercilla, no. 1534 (1964): 12-13.

Lippard, Lucy R. El Pop Art. Barcelona: Ediciones Destino, 1993.

López, José Pablo. «El arte pop hizo su estreno», Revista Ercilla, no. 1592 (1965): 11.

Mari, Marcelo. «Arte pop, arte conceptual y el golpe militar en Brasil (1964-1970)». Estudios sobre las culturas contemporáneas 24, no.48. (2022): 85-102. https://revistasacademicas.ucol.mx/index.php/culturascontemporaneas/article/view/610.

Masotta, Oscar. El «Pop-Art». Buenos Aires: Editorial Columba, 1967.

Masotta, Oscar. Revolución en el arte. Pop art, happenings y arte de los medios en la década de los sesenta. Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2004.

Mellado, Justo Pastor. «Cuestión de etiqueta», en Envío a la 5ª Bienal de Sydney. Arte & Textos, editado por Gonzalo Díaz et al.Santiago de Chile: Galería Sur, 1983.

Mellado, Justo Pastor. Meter la pata o presentación de la obra de Gonzalo Díaz en Chile Vive. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones VISUALA, 1987.

Parra, Catalina. Entrevista de Paulina Varas. «Contextualizándonos: Una conversación para comenzar». En Catalina Parra. El fantasma político del arte, editado por Paulina Varas, 15-22. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2011

Pedrosa, Mário. «Do pop americano ao sertanejo Dias». En Mario Pedrosa: Acadêmicos e modernos 3, coordinado por Otília Arantes, 367-372. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1998.

Smithson, Peter. Entrevista de Beatriz Colomina. «Amigos del futuro: Una conversación con Peter Smithson». En Doble exposición. Arquitectura a través del arte, editado por Beatriz Colomina, 88-108. Madrid: Akal, 2006.

Ramírez, Mari Carmen. «Cómo se yergue el ícono Frida». Conferencia en el Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 21 de septiembre de 2022.

Richard, Nelly. «Reivindicación de la sentimentalidad como discurso», La Separata, no. 4 (1982): 1-2.

Richard, Nelly. «Latin America: Cultures of repetition or cultures of difference?». En The fifth Biennale of Sydney. Private symbol: social metaphor, editado por Leon Paroissien. Sidney: Biennale of Sydney, 1984.

Nelly Richard. Márgenes e instituciones. Arte en Chile desde 1973. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2014.

Tibol, Raquel. Frida Kahlo: Crónica, testimonios y aproximaciones. Ciudad de México: Ediciones de Cultura Popular, 1977.

Traba, Marta. Historia abierta del arte colombiano. Bogotá: Ministerio de Cultura / Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, 2016.

VV.AA. Chile Vive: Muestra de Arte y Cultura. Madrid: Círculo de Bellas Artes, 1987.