1. Introduction

Informally, we often refer to myths as a set of facts of dubious veracity—traditionally understood as fantastical tales—which nevertheless enjoy enormous popularity and richness, filling the gaps in history and allowing us to indulge our imagination, which always persists in the search for explanatory narratives even when our language falls short. This is something that undoubtedly challenges certain precepts of historical rigor, but which we should not underestimate because of its ambiguous nature. Quite the contrary: we can use analytical rigor to ensure that these flourishing formulations and interpretations can stand on solid ground, without needing to omit the significance that emanates from their gray areas. In the case of Chilean artist Gonzalo Díaz, with all the retrospective enthusiasm currently surrounding his work given the presentation of his digital archive1See: https://www.gonzalodiaz.cl/ and his complete writings2Díaz, Gonzalo : Escritos 1980-2020 y Textos en Obra. Santiago de Chile, Ediciones Metales Pesados, 2025., we can still speak in mythological terms about his formative period, which was excluded from both publications, and even about what was left out of his most recent works.

As we know, the recent exhibition Gonzalo Díaz pintor, held at Il Posto in 2025 under the curatorial wing of Amalia Cross, did not originally intend to exclusively display paintings by Gonzalo Díaz produced in the 1980s, but also contemplated the presentation of a new canvas by the artist. In an interview published in El Mercurio in February of this year, he himself announced: “I intend, and I believe I will succeed, to have a new painting ready for March, even if the canvas is still wet when I hang it (…) paintings from the 1980s and one from 2025. It would be nice: a great arc of tension”3Silva, Daniela, Interview with Gonzalo Díaz, “I could make 500 artworks per minute, that is what i feel”. February 10, 2025. “Arte y Letras”, El Mercurio.. The truth is that for some time now, Díaz has been cheerfully expressing his insistent desire to return to painting, often with an ironic and disruptive attitude, as was the case with the collective exhibition El metal tranquilo de mi voz (“The Calm Metal of My Voice”)4y el metal tranquilo de mi voz, group exhibition at MAC – Museo de Arte Contemporáneo – July 2023 – September 2023. Artists exhibited: Eugenio Dittborn, Eugenio Téllez, Gonzalo Díaz Cuevas, Jorge Tacla, Natalia Babarovic, Pablo Langlois Prado., held at the MAC in Parque Forestal in mid-2023 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état in Chile. In that context, the artist stated: “And that’s the bun for which there is no oven. The 50th anniversary commemoration is not for putting on a show. (…) I always say that I don’t want to exhibit anymore, that I want to paint tiny watercolors”5Silva, Daniela. Interview with Gonzalo Díaz, “Being an artist is a curse”. July 17, 2023. Artes y Letras, El Mercurio..

Stunned by what he calls a “politically catastrophic”6Íbid context—and although known for his long career in installation art—Gonzalo Díaz then decided to return to painting, the mother tongue in which he was trained, or as he himself prefers to call it: “the mother tongue of the arts”7Díaz, Gonzalo. Turungo. Diálogo y archivo. Santiago: Il Posto y Metales Pesados, 2023, p. 50.. However, the painting promised for the exhibition Gonzalo Díaz pintor was never shown. After giving up on it for personal reasons, the artist left us with just a sketch of it. His return to painting was thus suspended—even though he himself says he never completely abandoned it8Íbid., 2.—and instead of this new work, the Il Posto exhibition presented certain pieces that had not seen the light of day for several decades. In any case, we will avoid reading this background as a mere failure; instead, we will try to consider how the impasse and the unfolding of attempts take on a decisive character in Díaz’s work, alluding to a state of forging and other nomenclatures related to the creation of sketches and work tables that have their own yield.

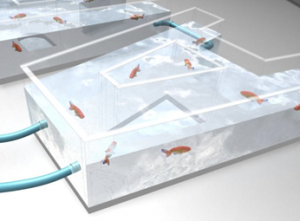

At this point, it is important to bear in mind the artist’s paradigmatic exhibitions, such as Banco/Marco de pruebas (Bench/Test Frame), with its allusion to testing processes; or more recently, the exhibition Notizen, “a German word meaning notes, sketches (…) and whose singular form can form the word Notizheft, (…) notebook”9Díaz, Gonzalo. 2020. Notizen: p. 3. Santiago, Chile: D21 Editores.. Similarly, there are numerous expressly provisional works by Díaz, and we also see that many pieces “conceived but never executed” have been the subject of considerable critical attention, as is the case with the work Vidas paralelas (Parallel Lives)10“The work was to consist of two series created in two-dimensional formats—diptychs, triptychs, and polyptychs—that would aim to construct a general reflection on the ebb and flow of time in the process of remembrance, establishing through parallel images the impossibility of establishing any hierarchy between fact and memory. (…) Díaz sketched out the idea for this scene, which leads to the fabulous theme of the theater of history, by turning to Plutarch’s Parallel Lives to project, limiting himself as Plutarch did to contrasting biographical pairs of Greeks and Romans while avoiding the narration of events, a kind of visual essay that this time would connect the lives of Allende and Pinochet.” (Galende, Federico. 2017. La República Perdida: un ensayo no visual sobre Gonzalo Díaz: pp. 91-92. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria). Later, we find a photograph of Allende in the work that Díaz created for the 8Tintas project. Díaz says in the biography of the work in the archive: “The child is Salvador Allende at approximately four years of age”, a portrait linked to the DATA exhibition, which was originally going to be presented at the Gasco Gallery, but the project was censored when it became known that the works were going to address the figures of Agusto Pinochet and Salvador Allende. ”This child looks at his unknown future. He does not yet have a biography, so to speak. He does not even suspect what he will experience. He has a special future in store for him.” (Díaz, Gonzalo. 2010. Text about the artwork En un abrir y cerrar de ojos, extracted from the Gonzalo Díaz Archive)., discussed by Federico Galende in La República Perdida11Galende, Federico. 2017. La República Perdida: un ensayo no visual sobre Gonzalo Díaz. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria., or the work Los cuatro secretos del arte contemporáneo (The Four Secrets of Contemporary Art), which Díaz describes to Hans Ulrich Obrist in the book Conversations in Chile12Los cuatro secretos del arte contemporáneo. Construction of performance scenes designed to be photographed (approximately 350 x 216 cm each). The four events correspond to four formal moments of revelation. Cinematographic treatment of sculptural painting motifs. They thematize the primal psychoanalytic scene, combined with an annunciation scene, in which Díaz would appear in a suit, and which even had actress Aline Küppenhei in mind to play the mythological angel. In each of the four panels, the little black dog would appear at the artist’s feet as a witness to verisimilitude, with the figures relating to each other in different ways through their body language, to four works by Marcel Duchamp, materially reproduced. The Fountain, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy, Bicycle Wheel, and With Hidden Noise. (Ulrich Obrist, Hans. 2020. Conversations in Chile: p. 199-201. Santiago, Chile: D21 Editores).. We even know of a work by Díaz that, despite having been produced and exhibited, remained in the category of “unrealized,” namely Death in Venice (2005). Due to negligence on the part of the Chilean committee in charge of its presentation at the 51st Venice Biennale, the Biennale organization, anticipating possible damage to property (due to the weight of the 450 liters of water contained in the work), assigned Díaz a section of the garden instead of the room for which his work had been specially designed. According to the artist, without the reflections of the sumptuous Murano glass chandelier in the hall of the Palazzo Cavalli Franchetti, and exposed to the heat outside, the work not only went unnoticed but also failed technically, which is why he chose to disregard the records of the event and instead keep the digital renderings that showed its ideal state of gestation (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Render de la obra Muerte en Venecia (2005) presentada por Gonzalo Díaz en la 51° Bienal de Venecia. Imagen contenida en su catálogo de exposición. Archivo Gonzalo Díaz.

It is with all these cases in mind that we allow ourselves to include “provisional materials” in this reflection, such as the aforementioned sketch of the work that was intended to be presented in Gonzalo Díaz pintor. And it is by virtue of Díaz’s express desire to “return to painting” that we propose connecting the mouth of the snake with its tail and rescuing the little information we have about this sketch to use it as a map in a broader reading of the body of work that makes up his early period, a period that has been scarcely analyzed by critics and which, for the purposes of this research, begins with the paintings in the El Paraíso Perdido (“Paradise Lost”) series, dating from 1973 until Díaz’s departure for Florence in 1979.

2. Marcación del territorio / Tratado de Grünewald

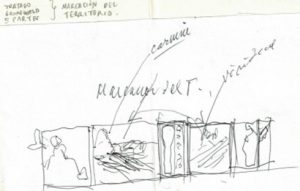

As we said, of what was to be the new painting destined to be exhibited in Gonzalo Díaz pintor, to date we only have a sketch made by the artist in a notebook belonging to Amalia Cross, in addition to his comments about a stiff arm that leaves its particular mark on the surface13Silva, Daniela, Interview with Gonzalo Díaz, “I could make 500 artworks per minute, that is what i feel”. February 10, 2025. “Arte y Letras”, El Mercurio.. Regarding the formal finish of the piece, we know that it would be composed of five panels (fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Gonzalo Díaz, boceto realizado en la de libreta Amalia Cross con motivo de la pintura que planeaba realizar para la exposición Gonzalo Díaz, pintor.

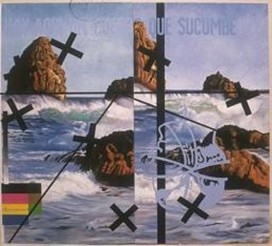

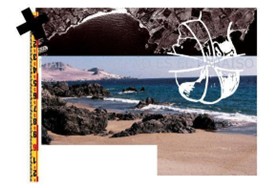

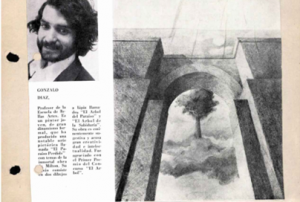

Regarding the content of this work, Consuelo Rodriguez tells us in the epilogue to her compilation of Díaz’s writings that the artist spoke to her personally about what his new polyptychs would be like. These were intended to form part of the series Marcación del Territorio (Marking the Territory), produced mainly between 1986 and 1987, a set of oil paintings of different Chilean landscapes—the desert, the sea, and the mountains—which Díaz mounted alongside aerogrammetric photographs (figs. 3, 4, and 5).

Fig. 3. Gonzalo Díaz, Marcación del Territorio (1987). Imágenes del Archivo Gonzalo Díaz.

Fig. 4. Gonzalo Díaz, HIPO TESIS, de la serie Marcación del Territorio (1987). Archivo Gonzalo Díaz.

Reconstructing his conversation with Díaz, Rodriguez mentions that the first panel of his new polyptych was going to depict the waiter from the Chilean wine brand Santa Carolina—an advertising caricature cited in Marcación de territorio and other works by the artist, such as Let me see if you can run as fast as me (1984)—with his arm holding the tray with the bottle of wine out of frame. On the other hand, in the second panel, we would see a new version of the seascape with the rocks that we see in the Marcación del Territorio piece entitled Para Escribir en el Cielo (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Gonzalo Díaz, Para Escribir en el Cielo de la serie Marcación del Territorio (1986). Archivo Gonzalo Díaz.

In the third panel of the work, Rodriguez suggests that a thigh would appear in a vertical position accompanied by a small word made of neon: Chthaon, which corresponds to the name of the archangel who controls the left thigh according to the Apocryphal Gospel of John. The fourth panel would be occupied by a viridian green wash representing the image of the Atacama Desert. And the last panel would close the right side of the polyptych with another advertising figure previously cited in numerous works by Diaz: the woman dressed in the traditional Dutch costume of the Chilean detergent brand Klenzo, with her hand outside the frame. Rodríguez also recounts that Díaz told him about his plan to make another polyptych with the same figures and similar landscapes, but with different frames, in which he would draw a right thigh and inscribe in neon the name of the archangel Charcharb, who, according to the apocryphal gospel of the Nag Hammadi manuscripts, governs this part of the body14Rodriguez Consuelo, Amor, el mundo es mi representación. Epilogue of Gonzalo Díaz: Escritos 1980-2020 y Textos en Obra. Santiago, Chile, Ediciones Metales Pesados, 2025, p. 493-494..

Now, if we return to Díaz’s sketch, we find a note that reads: Tratado de Grünewald (“Grünewald’s Treatise”). This may refer to a conversation between Gonzalo Díaz and Federico Galende published in the book Turungo, in which the artist talks about the only pilgrimage he has ever made specifically to see a painting, referring to his visit to the city of Colmar to see Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1516) by Matthias Grünewald: a set of coordinated paintings with the technical prowess of sculptor Nicolas de Haguenau, who built a structure of movable panels capable of opening like doors, allowing each one to be displayed in various arrangements (fig. 6). In Díaz’s words: a decisive journey from which he would emerge transformed, regretting only that he had not made it forty years earlier15Díaz, Gonzalo. 2023. Turungo: diálogo & archivo. p. 50. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Metales Pesados.

Fig. 6. De izquierda a derecha, se aprecia la apertura sucesiva de los paneles que componen el Retablo de Isenheim (1516). Fotogramas extraídos del documental El retablo de los ardientes – Matthias Grünewald, de la serie Palettes, producción televisiva francesa escrita y dirigida por Alain Jaubert.

Of course, we cannot definitively determine the relevance of this altarpiece in Díaz’s work. And beyond its pilgrimage, we cannot say for certain when the artist became familiar with this series of images and their mounting system. Nevertheless, it is worth examining them in the context of his own body of work, as they echoes that allow us to conjecture that, beyond being a model for the paintings intended for his last exhibition at Il Posto, they could be a collection of motifs that appear at different moments in his career, from his earliest stage to the present day.

For example, when inspecting the altarpiece, we are confronted with a stark image of the crucifixion, with Mary Magdalene joining her hands like suns while constraining a diffuse horizon in a supplicating pose (fig. 7). This image is, in its own way, the figuration of a restorative desire that has troubled Díaz since his beginnings: the relentless fate of humanity mired in longing, in the need to conquer the paradise it has lost16Díaz, Gonzalo. 1979. PARAISO PERDIDO: consideraciones acerca de la posibilidad del arte y su redención. Thesis to qualify for the academic degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in Painting. Advisor: Luis Advis V. University of Chile, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Art, Macul Campus.. A desire to restore the union between heaven and earth in order to conquer the primal return, which we also see in works such as Madre, esto no es el paraíso (Mother, this is not paradise) (2010) (fig. 8).

Fig. 7. Matthias Grünewald, detalle de María Magdalena suplicante en el panel de La Crucifixión del Retablo de Isenheim (1516).

Fig. 8. Gonzalo Díaz, Madre, esto no es el paraíso (2010).

On the other hand, in Grünwald’s Mocking of Christ (fig. 9), we can identify—at least intuitively—two other references taken by Díaz: the bandaged head he took from a Boy Scouts manual, used in the Gonzalo Díaz Archive (2025) and previously in the work Mother, This Is Not Paradise (2010); and, as a textual variation on the heavy blow that one of the soldiers strikes on Christ’s blind head, the image evoked by the title Turungo17Díaz, Gonzalo. 2023. Turungo: diálogo & archivo. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Metales Pesados., a word that refers to a sharp blow to the forehead, a slap that abruptly wakes someone up. In the transfer of this gesture, traumatic shock is combined with crude humor in the face of a disconcerting revelation. What we would call in Chilean Spanish la caída de teja (“the fall of the tile”).

Fig. 9. Matthias Grünewald, El Escarnio de Cristo (1505).

Delving deeper and deeper into the altarpiece, on the right side of the last opening of its doors, we find The Temptations of Saint Anthony (fig. 10). As we shall see, this character appears with his head seized by a demon, while facing various creatures similar to those that make up the Paradise Lost series (fig. 11).

Fig. 10. Matthias Grünewald, Las Tentaciones de San Antonio en el Retablo de Isenheim (1516).

Fig. 11. Gonzalo Díaz, Cancerbero (1977-1978).

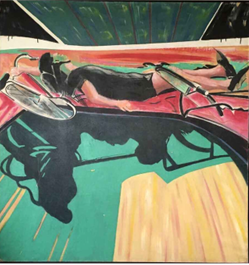

On the other hand, if we return to the lower part of the altarpiece, we see a Burial of Christ (fig. 12) that reminds us of the bodies lying horizontally in the cycling accidents that feature in the work Los hijos de la dicha (“The Children of Happiness”) (1981), a diptych created by Díaz during his stay in Florence (fig. 13).

Fig. 12. Matthias Grünewald, panel de El Entierro en el Retablo de Isenheim (1516).

Fig. 13. Gonzalo Díaz, Los Hijos de la Dicha (1981)

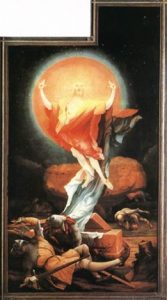

Then, on the right panel of the second opening of the altarpiece doors, there is a scene of the resurrection in which we can see a soldier falling in foreshortening, rolling headfirst toward us (fig. 14), also cited in one of the paintings of Paradise Lost18This work is part of a series of Cerberuses that the artist created during that period. A mythological dog that guards the entrance to hell. It was exhibited at the Center for Architectural Studies (CEDLA) in an exhibition called El Paraíso Perdido (“Paradise Lost”), and years later it would participate in the XV International Biennial of Sao Paulo. (fig. 15), as well as in the third panel of The Children of Happiness (Panel C: Aspectos ocultos (El) de la Ronda Nocturna) (fig. 16).

Fig. 14. Matthias Grünewald, panel de La Resurrección en el Retablo de Isenheim (1516)

Fig. 15. Registros de El Paraíso Perdido (1977-1978) contenidos en PARAÍSO PERDIDO: consideraciones acerca de la posibilidad del arte y su redención (1979).

Fig. 16. Gonzalo Díaz, Los Hijos de la Dicha o Introducción al paisaje chileno. Panel C: Aspectos ocultos (El) de la Ronda Nocturna.

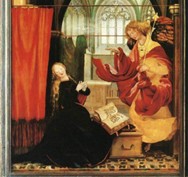

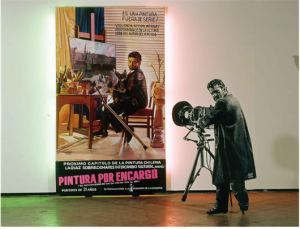

Finally, on the counterpart to the panel depicting The Resurrection of Christ, we see a scene from The Annunciation (fig. 17), adorned with various carmine and viridian fabrics (colors indicated in the sketch of Díaz’s last work, incidentally), which hang just like the cloths in Historia Sentimental de la Pintura Chilena (“Sentimental History of Chilean Painting”) (1982) mounted in the exhibition Gonzalo Díaz pintor (fig. 18). Certain elements of this same scene also seem to be invoked in Pintura por Encargo (“Painting on Commission”) (1985), where we can see the transition from viridian to carmine executed in neon and the same pose of the Virgin turned away (fig. 19).

Fig. 17. Matthias Grünewald, panel de La Anunciación en el Retablo de Isenheim (1516).

Fig. 18. Serie incluída en La Historia Sentimental de la Pintura Chilena en registros de la exposición Gonzalo Díaz pintor, Il Posto (2025).

Fig. 19. Luz viridio y carmín en reencuadre de Pintura por Encargo, Gonzalo Díaz (1985)

As we have seen, Matthias Grunewald and Nicolas de Haguenau’s Isenheim Altarpiece is mentioned in the sketch for Díaz’s last painting, perhaps as a reference for this work, although it is not entirely clear under what parameters. The only thing we can say for sure is that the artist wanted to extract from the scene of the Annunciation in the altarpiece the transition from carmine red to viridian green, a color scheme that would be invoked alongside a series of references to apocryphal gospels crossed with the wealth of psychoanalytic notions that often appear in his work. In this case, these notions are related to the Urszene or primal scene, which Freud understood as the repressed or simply imagined visualization by the child of his parents’ sexual intercourse. This situation illustrates the curiosity we feel in the face of the unsolvable mystery of life and its origins, an issue that occupies a fundamental place in Gonzalo Díaz’s work and is linked to the problem of the phenomenal appearance of consciousness, the complexes of the intelligible, and the unstable conformation of territory.

3. A retained abandonment, a latent return

Before delving into an analysis of Gonzalo Díaz’s early works, it is necessary to clarify what we mean by the artist’s return and foundational mythology. Since we will not only be discussing his early beginnings as a painter, but also a dense philosophical notion that Díaz has carried with him to this day, that is, an idea of foundation from which the artist reflects on the phenomenal appearance of consciousness and, in very broad terms, on our desire to make a place for ourselves in the world, as well as on the complexities of the intelligible and the unstable conformation of our territory.

Gonzalo Díaz makes numerous references to a constrained desire to return, which is evident from the earliest works in the series El Paraíso Perdido, dated between 1973 and 1979. Later, in Historia sentimental de la pintura chilena (1982), the desire to return to the mother emerges, sublimated in the surrogate mother: the provincial girl from the Klenzo detergent advertisement as a substitute for the Tuscan Madonnas that the artist saw on his trip to Florence, the cradle of a profuse tradition of fine arts that never existed in Chile; or a rescue of that orphaned homeland, that Lost Republic, as Federico Galende says when he asserts that, in much of his work, Gonzalo Díaz has done nothing more than “visually rethink the image of a republic in absence (…) an abandoned dovecote”19Galende, Federico. 2017. La República Perdida: un ensayo no visual sobre Gonzalo Díaz. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria, p. 83-84.. Here, before this original Eden, in these lost foundations and in the attempt to restore them, we find the artist’s circular key, identified in certain traces of the psychoanalytic lexicon that accompanied him from his beginnings, to other cases where he would leave the reference open, such as in Lonquén 10 años with its reference to Freud’s writings. Likewise, we will of course see the formal particularity of certain works that will find their return inscribed in various motifs of spirals or cyclones. From Los Hijos de la Dicha —and particularly Panel C, which we have already referred to above—to the parallels of the Riemann Cone in Tratado del Entendimiento Humano (“Treatise on Human Understanding”), Revista Cultural and Índice (fig. 20), or the machines included in El Festín de Baltazar (“Balthazar’s Feast”) and Notizen, among others.

Fig. 20. Gonzalo Díaz, El Perro de Heráclito. Índice, 2010.

As in the Christian narrative contained in Grünewald’s series, the Annunciation, birth, burial, and resurrection are also, at the same time, the cycle of everything that rises in anticipation of its eventual fall. For his part, Díaz is marked by a biographical detail: the polio that has afflicted him since childhood and which, with the particular complications it presents for mobility, provides a counterpart to certain recurring operations in his work, where retaining barriers, jacks, and flimsy assembly systems deploy their own orthopedics in space. Some of this can be clarified by reviewing his early writings, where he remarks: “Art is never made on solid ground. Otherwise, it would lose all its consistency.” (…) “The artist always lives in danger of losing his footing and falling into the abyss.” He then goes on to declare: “Moreover, in maturity, man thinks and intuits better while walking. Just as a child walks, he will talk; just as he talks, he will think”20Díaz, Gonzalo. 1979. PARAISO PERDIDO: consideraciones acerca de la posibilidad del arte y su redención. Thesis to qualify for the academic degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in Painting. Advisor: Luis Advis V. University of Chile, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Art, Macul Campus, p. 2-6.. And it is remarkable, beyond this relationship between feet, how between the lines the artist accuses himself, by deduction, of being the master of a particular stupidity, subliminally linking the difficulty of his movement with a certain restriction or immaturity in speech and thought in general. We have already heard him refer to himself as “retarded” when talking about Lonquén 10 años and the time it took him to digest the political events that gave rise to that work21Díaz, Gonzalo. 2010. Interview with Cristián Warken in La belleza de pensar. Santiago, Chile: ARTV. However, and curiously, in Díaz, the cognitive impasse is tied to what has been a masterful effort of language, to the point of thematizing intellectuality in works such as Œuvres Complètes (2006), Trivium ad usum communitatis (2006), Quadrivium ad usum Delphini (1998), among others that deal with the categories of knowledge, rhetoric, and the archetypal figure of the scholar.

To round off this reflection and outline the link between fragile ground, childhood, and uprising, and in passing establish this individual-universal, or personal-political, relationship articulated in Gonzalo Díaz’s mythology, let us look at this excerpt from an anecdote about the artist’s childhood that accompanied the work El 5 de octubre de 1957 (2018):

“Es la escena de un niño de 10 años que espera sentado en una camilla, a una hora muy temprana del día 5 de octubre de 1957, en un subterráneo del Instituto Traumatológico de Santiago, que le ajusten la órtesis que debía usar en su pierna derecha. Era un paciente habitual de ese establecimiento público. Frente a la camilla y contra el muro, el niño podía observar siempre una extraña máquina que mucho después supo –despejando lo ominoso de su apariencia– que servía para ejercicios kinesiológicos de tracción cervical. Desde los talleres de atrás del establecimiento y entre ruidos de máquinas se escuchaba una radio que informaba del lanzamiento del primer satélite artificial, por parte de la Unión Soviética. Su nombre mágico: Sputnik.” (…) “Nos ponían esas cosas redondas de las romanas y le ponían 800 gr., o 1 kilo, lo que el médico calculaba que era necesario, y uno se sentaba, a mí me hicieron ese tratamiento en la posta, y era exquisito, era como volarse. Uno se quedaba dormido”22Díaz, Gonzalo. 2018. El 5 de octubre de 1957 (exhibition text). Santiago, Chile: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes..

This testimony highlights, among other things, a foreshadowing of what would become the experiment with socialism in Chile, which failed to take root when it suffered its own coup and downfall. In the context of trauma and revelation, Díaz makes numerous references to a type of cognitive process closely linked to the interstice between consciousness and sleep, a revelation attributed to the fall, a form of loss and promise of return to an original state. We see this clearly in some fragments of his bachelor’s thesis, where Díaz quotes Schiller’s premise in large letters: “The supreme goal of art is the representation of the supersensible,” and then adds:

El Arte debe su existencia a la Humanidad que así sigue su camino más allá del Paraíso Perdido, buscando recobrarlo ¿Acaso sin haber pérdida, hay abismo? ¿Acaso sin abismo, es posible tender puentes, más aún, es necesario? (…) El que pierde algo, se separa de algo. Se adquiere con ello una distancia que se va agrandando y que se transforma, finalmente, en punto de vista. Como los astros. De entre todo el actuar del hombre, el Arte es aquel especial actuar que nace justo allí en medio de la pérdida y por ella. Nace bajo el imperativo del recuerdo y se despliega inevitablemente en la construcción de puentes23Díaz, Gonzalo. 1979. PARAISO PERDIDO: consideraciones acerca de la posibilidad del arte y su redención. Thesis to qualify for the academic degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in Painting. Advisor: Luis Advis V. University of Chile, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Art, Macul Campus, p. 17-19..

With this, we now have some key concepts and figures to think broadly about the implications of Paradise Lost and the return in Díaz’s work. From now on, we will fully explore the formative stage of his work.

4. Díaz Mithology

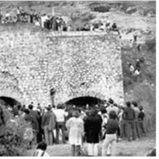

The earliest work recorded in the Gonzalo Díaz Archive is El árbol del paraíso (“The Tree of Paradise”) (1975–76) (fig. 21), in which we recognize the figure of the semicircular arch threshold that will reappear in Lonquén 10 años (1989), with reference to the ovens of Lonquén (figs. 22 and 23); in Unidos en la Gloria y en la Muerte (“United in Glory and Death”) (1997), with the use of the façade of the Museum of Fine Arts (fig. 24); and in Quadrivium ad usum Delphini (1998), with the train tunnel (fig. 25).

Fig. 21. Gonzalo Díaz, El árbol del paraíso (1975).

Fig. 22. Gonzalo Díaz, Lonquén. 10 años (1989).

Fig. 23. Luis Navarro, fotografía de 1979 de los hornos de Lonquén.

Fig. 24. Gonzalo Díaz, Unidos en la Gloria y en la Muerte (1997).

Fig. 25. Gonzalo Díaz, Quadrivium ad usum Delphini (1998).

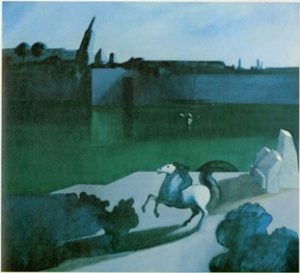

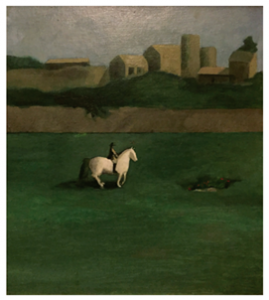

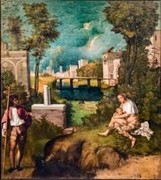

Whether identified as the neoclassical archway to paradise or the entrance to the pit of hell, to examine this threshold figure more closely, we must turn to San Jorge y el Dragón – Creación de la conciencia (“Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness”) (1975-76) (fig. 26), whose equestrian motif can be traced back to a painting by Díaz found in the Pérez-Stephens Collection catalog, entitled Paradise Lost (1973) (fig. 27). Close to Raphael Sanzio’s Saint George and the Dragon (1504) (fig. 28), with the optical tricks of Giorgione’s The Tempest (1508) (fig. 29), and something of Paolo Uccelo’s Battle of San Romano (1436-1440) (figs. 30 and 31), which Díaz himself will cite in Políticas de la Perspectiva (“Politics of perspective”) (2010) (fig. 32), the first of these paintings presents different Renaissance references, although without the essayistic character that will later define the artist’s intertexts. These are metaphysical motifs, where the limits of existence are plainly explored. The Styx, which gives this work its alternative title24It should be noted that two different versions of this painting have been found, which, although they appear to correspond to the same painting, differ both in their color tones and in their titles. Firstly, the one we see in the Gonzalo Díaz Archive is catalogued as: Saint George and the Dragon – Styx Lagoon (1975-76), with more earthy and grayish tones; while on the other hand, when consulting the exhibition catalog of Three Painters, Three Sculptors, and a Poet (1977) at the Época Gallery, we see the same image with a more saturated color finish, under the name Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness. In the Gonzalo Díaz Archive, the first (which we can see on a lectern) even differs between the titles used in the caption (“GD-O-0003 Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness”) and in its work file (“Saint George and the Dragon – Styx Lagoon”). Meanwhile, Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness is listed as a separate work, whose image has not yet been entered. In this article, in order to avoid confusion, we have chosen to refer exclusively to Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness, using the entry obtained from the aforementioned catalog courtesy of Pedro Montes, and I will refer to the Stygian Lagoon only to preserve the mythological reference provided by its title., corresponds in Ovid’s mythology to the boundary with Tartarus or the underworld, and thus in this canvas we see characters lost in shadows and a suggestive use of counterform, so that the physiognomy of certain somber and inert silhouettes seems animated by a secret vitality.

Fig. 26. Gonzalo Díaz, San Jorge y el Dragón – Creación de la conciencia. Catálogo de exposición Tres pintores tres escultores y un poeta (1977). Galería Época.

Fig. 27. Gonzalo Díaz, El Paraíso Perdido (1973). Colección Pérez-Stephens Primera edición, Talca, abril de 2022. Editorial Universidad de Talca.

Fig. 28. Gigone, La tempestad (1508).

Fig. 29. Rafael Sanzio, San Jorge y el Dragón (1504).

Fig. 30 y 31. Reencuadres de Batalla de San Romano de Ucello (1436-1440).

Fig. 32. Gonzalo Díaz, Políticas de la Perspectiva (2010).

Suggestive figures appear and disappear as you walk through Díaz’s Saint George and the Dragon, like Eurydices who vanish when you turn around. A woman can be glimpsed riding and embracing the horse, but when you look again, she blends into the mane and the shadow on the side of the horse. The strip of land in front of the animal arches like a claw, and behind it, in an effect of pareidolia, a hand made of blocks of rock points toward the sky25In Díaz, the stone pointing to the sky drags its inert weight, signaling its celestial origin, like El Paseante (2009), which ended up lost in remote places according to Goethe’s aforementioned story, O Civitas Dei de Notizen, in which the artist signs names like angels on these anomalous ballasts. Adding to this background is Raphael’s Plato pointing to the sky in his School of Athens. Above the rider, a third arrow can be seen, a distant tower leaning in her direction, tempted to collapse. And closer to us, the shadow of a human bust is camouflaged in the form of dense bushes (fig. 33). Is this not the one who came to read the word art under his own shadow, as stated in Gonzalo Díaz’s work Eclipse26Eclipse (2007), work presented at Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany. “At first, only the light from a spotlight can be seen in the dark room, but when you approach the mark on the wall, the German text appears in your own shadow: DU KOMMST SUM HERZEN DEUTSCHLANDS NUR UM DAS WORT KUNST UNTER DEINEM EIGENEN SCHATTEN ZU LESEN (You have come to the heart of Germany just to read the word art under your own shadow). Gonzalo Díaz Archive. (fig. 34)?

Fig. 33. Reencuadre de San Jorge y el Dragón – Creación de la conciencia, Catálogo de exposición Tres pintores tres escultores y un poeta, 1977. Galería Época.

Fig. 34. Gonzalo Díaz, Eclipse, 2007.

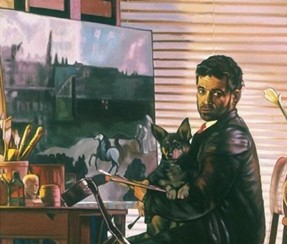

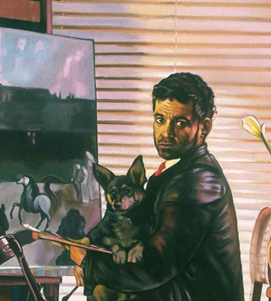

As in Eclipse, in Saint George and the Dragon the artist’s curly bust is stamped on the canvas as if there were a large spotlight behind him, roughly casting the flickering shadow of his figure, thereby accusing the presence of the viewer hidden outside the frame. This interplay between the inside and outside of the representation is reinforced in the version of Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness cited in Pintura por Encargo (1985) (fig. 35). Not only do we identify the painter in front of the canvas on his easel, but the proximity between the “rock hand” in the painting and the portrayed body of Díaz enables an anthropomorphic relationship and, with it, continuity between the inside and outside of the painting (fig. 36).

Fig. 35. Gonzalo Díaz, Pintura por Encargo (1985).

Fig. 36. Reencuadre de Pintura por Encargo, Gonzalo Díaz (1985).

Now, it should be noted that in Pintura por Encargo, the landscape of Saint George and the Dragon has become more of a modern port than a closed fortress. And if we look closely, the fingers of the “stone hand” have taken the form of three women in mourning (fig. 37), which may refer to the biblical scene of the three Marys in front of the empty tomb. The image of the stump or hidden hand presented by Chica Klenzo in La Historia Sentimental de la Pintura Chilena (1982) also resonates here, which can in turn be thought of as the painter’s petrified hand. And here I conjecture: this hand perhaps obeys a historical moment in which the organic nature of the manual gesture is lost in exchange for technical reproducibility (“without hands: instead of hands, manual labor”27Valdés, Adriana. “Gonzalo Diaz: pintura por encargo”. In Composición de Lugar: Escritos sobre cultura, p. 52. Santiago: Universitaria, 1996.). But it can also be linked to other impasses, related to the theoretical speculation that to a certain extent prevents Díaz from fully incorporating himself into the material sensuality of artistic production.

Fig. 37. Reencuadre de Pintura por Encargo, Gonzalo Díaz (1985).

To conclude, let’s look at the details: a yellow cove appears like a spotlight in the artist’s eyes, who otherwise seems to cast different shadows: one realistic, scattered in the violet tones of the wall that blends into the sky in the painting; and another allegorical, stamped in black on the painting. Then, between this shadow and him, we find the beast: a lapdog that looks impartially at the viewer, aware of being observed.

Fig. 38. Reencuadre de Pintura por Encargo, Gonzalo Díaz (1985).

Returning to the original version of Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness, when we examine the lower left side of the work (fig. 39), we recognize a shadow that we can associate with the posture adopted by the figures in the diptychs and triptychs of Los hijos de la dicha (1981) created by Gonzalo Díaz in Florence (fig. 40). We are thinking here particularly of that supine pose that refers to a state of unfolding or incorporeal transcendence, a psychic state altered by the passage from wakefulness to the world of dreams.

Fig. 39. Reencuadre de San Jorge y el Dragón – Creación de la Conciencia, Catálogo de exposición Tres pintores tres escultores y un poeta, 1977. Galería Época.

Fig. 40. Gonzalo Díaz, Los Hijos de la Dicha (díptico de Florencia), 1981.

The horizontal posture of the reclining figure we identify here has its corresponding ascent, emphasized in Díaz’s painting by the vertical points of the different towers and the stone hand pointing to the sky. And it is possible to recognize in this perpendicular correspondence of axes a Cartesian planning, a planimetric scheme whose representation of depth is declined in complex philosophical implications. Here it is worth pausing to remember that, in dimensional terms, we have on the one hand the Cartesian relationships of horizontality and verticality contained by the surface of the painting and, on the other hand, a third dimension that allows us to enter the image of the painting: depth. But in the Renaissance, pictorial treatises on perspective and the entry of depth into representation, together with the metaphysical idea of a point where parallel lines converge, are strongly linked to the problem of representing infinity; so that it is not only the third dimension that begins to be worked on the two-dimensional support, but also the idea of a fourth dimension in which the visible space around us would be contained and which, before relating to the gyroscope of our optical vision, would be linked to the perception of the mind and the simultaneous superimposition of times that is characteristic of the passages of the unconscious28The fourth dimension is a contemporary term that nevertheless has its religious origins in antiquity and in multiple cultures, where artists and writers sought to account for a metaphysical space belonging to an absolute time, beyond the past, present, and future. To think about this problem from the Renaissance but based on the aforementioned contemporary nomenclatures, I recommend reading Marcel Duchamp’s writings in his Green Box (Duchamp, M. Writings: Duchamp du signe. Editorial Gustavo Gil. Barcelona, 1978), which contain a series of notes in which he describes the elaboration of a diagram capable of interweaving the second, third, and fourth dimensions for the creation of his Large Glass (1923), which was notably influenced by his studies of the treatise on perspective in the Renaissance during the period he worked at the Sainte Geneviève Library in Paris (as recounted in: Cavanne, P. Conversation with Duchamp. UDP. Santiago, 2023.). On the other hand, we find a particular treatment of these problems in Piero della Francesca’s series of frescoes La Leggenda della Vera Croce (The Legend of the True Cross), where the Italian geometer and painter favored—rather than a chronological arrangement of the panels—the proliferation of cross-relationships across the multiple scenes that make up the whole. Among them, Constantine’s Dream plays a notable role, as it links the unconscious to the simultaneous diversity of times, displaying a two-dimensional arrangement marked by the irruption of depth and linked in turn to the various scenes that relate to it through the correlation of their compositional lines.

It follows that the so-called scientific perspective is not exempt from religious implications and paradoxes, which Díaz himself was well aware of. To put it in more illustrative terms, we can identify the representation of the transition from the second to the third dimension in medieval prints that feature the first attempts at using perspective, for example, in Matthias Grünewald’s The Resurrection of Christ, where Christ (represented frontally) and the soldiers (in perspective foreshortening) are contained in a luminous sphere that signifies the resurrection and with it the defeat of any temporal distinction between before and after. It is precisely there that the transition from the third to the fourth dimension takes place, that is, as we have said: a physical space subject to the simultaneous behavior of time that overlaps the linear fiction of its advance, the effect of which can be verified daily in the memory and projection that overlap in the experience of what we call the present.

Fig. 41. Matthias Grünewald, panel de La Resurrección de Cristo del Retablo de Isenheim (1516).

As in Grünewald’s Resurrection of Christ, in Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness there is also a break with the Cartesian plane that introduces a sense of vertigo in the face of the depth of perspective, alluding to a step towards a dimension that transcends our definitions of space and, therefore, our notion of demarcable territory. To reinforce this, I would like to make three observations:

First, it should be mentioned that in Las Faenas de Babel (“The Labors of Babel”) (1977-1978), a painting by Díaz reproduced in the fourth issue of the magazine El arco y la Lira29El Arco y la Lira (N.º 4). Facultad de Bellas Artes, Universidad de Chile (1979). P. 28., we see the same scene as in Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness, viewed from the opposite angle. In other words, the painting is mirrored in artificial reversals that refer to a shared space and relate both images (figs. 42 and 43).

Figs. 42 y 43. Gonzalo Díaz, Las faenas de Babel, Paraíso Perdido, en revista El Arco y la Lira N° 4, 1979 y Gonzalo Díaz, San Jorge y el Dragón – Creación de la conciencia, en Catálogo de exposición Tres pintores tres escultores y un poeta, Galería Época, 1977.

Fig. 44. Registro de la pintura Las Faenas de Babel de Gonzalo Díaz volteada en transparencia sobre su San Jorge y el Dragón – Creación de la conciencia, ambas de 1979.

A transparency test—a simulation of the images meeting on their reverse side—allows us to appreciate the various connections between the compositional directions and the dialogue between the figures that populate each painting (fig. 44). Despite the difference in scale between the two canvases, we can surmise that the resulting ensemble would be an object that can be physically surrounded. However, in metaphysical terms, it would be more like the midpoint between two visions: the artist’s point of view in Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness, and the point of view of that revelation that returns the gaze to the first canvas in The Labors of Babel. In this way, the damsels on steeds become beasts and our shadow collides with the torn boundary we believe we have reached, while the artist witnesses the shreds of a tight composition, kneeling in the background, barefoot and shirtless, his hands at hip level, ashamed and confined to his shadow, shying away from a horizon that tickles him like a finger on the back of his neck in the manner of a disturbing annunciation.

Secondly, as another example of a work that plays with the superimposition of images, we can cite the diptych of David and Goliath (1555) created by Daniele da Volterra based on a drawing by his master Michelangelo (figs. 45 and 46), a double-sided painting depicting the beheading of Goliath and invoking some of the motifs we have already reviewed: the fissure, blindness, the loss of the head, the fall, and a formal treatment of corners as thresholds that open up, which were notably present in the pictorial work of Gonzalo Díaz. But as we have mentioned, what stands out in the exercise carried out in Creation of Consciousness and The Labors of Babel—and what differentiates it from the sculptural finish of Volterra-Michelangelo’s work—is that Díaz, in a dizzying spatial effect, reverses the perspective of space, producing an object that we can surround and yet leaves us in the middle of two visions. This creates a paradoxical simultaneity between the action of walking around and turning our gaze, as also happens in the non-orientable surfaces that gained momentum in mathematical research in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, among which we find objects such as the Klein bottle30Such as Tratado del Entendimiento Humano (1992); La Escuela de Santiago, Mesa De Trabajo. El Tratado del Entendimiento Humano (1994); El Perro de Heráclito (2010), which Díaz graphically places in several of his works, and which is defined as a “non-orientable” surface in the sense that we cannot distinguish its interior from its exterior.

Figs. 45 y 46. David y Goliat de Daniele da Volterra (1555), anverso y reverso del cuadro.

Finally, as a third observation, it should be noted that in Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness, the rider’s cloak opens a small opening, a dark corner that tears the surface, inviting us to the other side. The horse’s mane and the rider’s cape allow us to glimpse the silhouette of a repulsive rat slipping away to its lair. And when we look closely (it is curious that we did not notice it before), we realize that these castles fit perfectly with the shape of the Lonquén ovens (fig. 47).

Fig. 47. Luis Navarro, fotografía de 1979 de los hornos de Lonquén.

This leads us to believe that Saint George and the Dragon – Creation of Consciousness, dated 1975–76 in Díaz’s archive, may have been misdated31The work Saint George and the Dragon – Styx Lagoon, which corresponds to the date indicated, uses the same motif and composition, varying only in its colors, dimensions, and title. For more information on this subject, please refer to footnote 24., as Luis Navarro’s well-known photograph of the Lonquén kilns was not published until 1978. In that case, we could speculate that what Díaz wanted to express in his painting was a political-metaphysical reflection that juxtaposed the disappearance of the bodies with the phenomenal appearance of consciousness and the workings of language. However, upon reviewing the catalog of the exhibition El Paraíso Perdido, we find that this painting was created long before the bodies were found in the Lonquén ovens. So we can only think of it as a curious coincidence, or perhaps an unconscious foreshadowing, a mysterious announcement in which the whereabouts of the bodies of the peasants who were murdered and disappeared during the dictatorship would have been revealed through the metaphysical motifs with which Díaz was working some years before the atrocious acts committed became known.

This premonitory relationship between the motifs in Gonzalo Díaz’s early paintings and the Lonquén mine is not something that the artist has ever made public. However, in a conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Díaz refers to the “palatial appearance” of “the semicircular arches in the Lonquén limestone mines”32Ulrich Obrist, Hans. 2020. Conversations in Chile: p. 189. Santiago, Chile: D21 Editores.. I think of the paranoid modesty and the impression the artist must have had when he saw this atrocious image that he had been painting all along without knowing it, and the incomprehensible revelation that it must have meant to him. Then, he would suddenly perceive the mandate that would emerge with this apparition: to bear the secret of the dreams that had been revealed to him33Reference to the phrase contained within the frames that make up the work Lonquén: 10 years (“EN ESTA CASA / EL 12 DE ENERO DE 1989 / LE FUE REVELADO A GONZALO DÍAZ / EL SECRETO DE LOS SUEÑOS”). This phrase was also paraphrased by the artist from the famous letter written by Sigmund Freud to his friend Wilhelm Fliess.[3].