1. Entry

The uncertainties that currently loom over the present, along with modifying expectations about the future, imperatively demand a rethinking of how we have related to time. Its teleological architecture, expressed as eternal progress, manifests a temporality in crisis that has become a race to nowhere, a characteristic inconsistent with the multitemporalities of contemporaneity. In this scenario, the contribution of resources such as the arts, images, and nature, which have persistently warned about temporalities that differ from traditional chronological ordering, becomes essential.

More than 150 years separate the works of contemporary artist Teresa Margolles (Culiacán, Mexico, 1963) and naturalist painter Mauricio Rugendas (Augsburg, Germany, 1802). Colonizations, independences, civil wars, dictatorships—all in between. However, these events have not been permanently buried. The layered character of Latin American temporalities provides fertile ground for considering the dialogue between untimely images. These images, in the words of Miguel Ángel Hernández, influence and are influenced by temporalities beyond them: “our knowledge of the past illuminates the present. It changes it, transforms it. And vice versa: the present illuminates the past, and in a way, rescues it”1Hernández, Miguel Ángel, “Prólogo. La historia del arte y el tiempo de la escritura”, in El tiempo de lo visual. La imagen en la historia, by Keith Moxey (Bilbao: Sans Soleil, 2015), 12-13.. Thus, within the synergy of images, nature, and the compression of time in Latin America, there lies a power that allows us to conceive strategies to untie the region’s current knots.

2. Grasping images, grasping time

To speak of images is to speak of time, even though their relationship is essentially conflicting. The way images manifest is through an interconnected network where they influence and contaminate each other reciprocally, regardless of the time and place in which they emerged. For Georges Didi-Huberman, “the image is timeless, absolute, eternal, escaping, by essence, historicity […] its temporality will not be recognized as such as long as the historical element that produces it does not become dialectized by the anachronic element that crosses it”2Georges Didi-Huberman, Ante el tiempo. Historia del arte y anacronismo de las imágenes (Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo Editora, 2011), 49.. Not being configured as a univocal narrative that chronologically recounts events, images are inherently a questioning of linear time.

The untimely juxtaposition of works and images created by Margolles and Rugendas responds to a demand emanating from their own proposals. The similarity in the processes, gestures, and iconography they use makes both projects speak to us about a particular way of observing the world and, given their insistence, present a question that calls for exploration. Furthermore, thinking about the temporal agency of these artists’ images gains even more relevance in the Latin American context, where the struggle for temporalities different from the Western one has been a distinctive feature of the region. Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui noted that, unlike the West, multiple temporalities can coexist synchronously in Latin America, at the same moment and place3In the author’s terms, the temporal cycles have been inaugurated in the Latin American context on the basis of deep historical wounds which, when not closed, initiate a process of coexistence of one with the other. In her words: “Esta simbiosis forma parte de un complejo proceso de renovación de contenidos mesiánicos y percepciones cíclicas de la historia, que sucede en distintas coyunturas históricas y en momentos de crisis y convulsión social”. In Silvia Riviera Cusicanqui, Oprimidos pero no vencidos (La Paz: La mirada salvaje, 2010), 200..

Thus, time is not something handed down but rather constructed through the meaning communities and societies assign to it. Jacques Attali observed that “every culture is built around a sense of time”4Jacques Attali, Historias del tiempo (Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004), 10. and by observing the works of Rugendas and Margolles, we see two modulations of time that, at first glance, differ yet coexist. The overlap of layers arises from a dislocated temporality created by the unique relationship humans establish with their environment, as well as the agency observed in the materials emerging from the natural and urban landscapes that both artists capture. In other words, a time built on the relationships that these entities establish.

Rugendas’ formula for capturing the distinctiveness of the scenes he portrays lies in the meticulous descriptive ability imprinted on each of his works. For this reason, he has been described as “a true chronicle draftsman, for beyond his plastic qualities, there exists an interest in the scenes themselves, which have the liveliness of narrative, a true colored chronicle”5Ricardo Bindis, I El despertar de la pintura en Chile (Santiago de Chile: Lord Cochrane Ediciones, 1979), 5.. The artist gazes upon the landscape, with every animal, plant, or human inscribed in a particular place within the territory. This was the case in Valparaíso: fascinated by the city’s movement, Rugendas obsessively dedicated over ten works to depict the winding paths leading to the port city.

In Bajada de Valparaíso (1841), the German painter captures the natural and urban landscape with unparalleled precision. Positioned in the coastal mountain range, Rugendas reproduces the local flora with such accuracy that it is even possible to identify the different plant species present. In the lower part of the painting, the budding branches of the litre decorate the path along which people and animals travel. Similarly, the quisco—a cactus native to the region—crowns the highest part of the painting. In the distant horizon, the city of Valparaíso timidly reveals its cathedral. Finally, at the center of the composition, a caravan of carts descends toward the city with the help of oxen, a dynamic that faithfully depicts the socioeconomic realities of those transporting goods to the port.

Fig. 1. Mauricio Rugendas, Bajada de Valparaíso, 1841

Although Rugendas’ pictorial approach draws upon the scientific thought derived from Alexander von Humboldt, his approach to these natural landscapes, previously unknown to him before arriving on the continent, is executed in an entirely unprejudiced manner. According to Pere Halm, the German painter:

He faces nature in an ingenuous and serene way, moved by its ever-varying richness and grandeur, and above all by the exuberance of the tropical world that fantastically unfolds before his eyes in Central and South America. Yet he is also determined to capture the essence of its own unique character6Peter Halm, “Johan Moritz Rugendas” en J. M. Rugendas en Chile (Prestel-Verlag: s/e, 1959). Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name..

In his gaze, there is no attempt to rationalize what he was observing on the continent from a Western perspective; rather, Rugendas allows himself to be struck by the potential of the American landscape.

The fact that every plant, animal, and face can be attributed to a particular place on the continent speaks to an acknowledgment of the agency inherent in the depicted settings. Thus, through an appreciation of natural and cultural diversity, this artistic project highlights a worldview in which humans are an integral part of a broader ecosystem, one that challenges the dichotomy between humans and nature. And although it would be inaccurate to suggest that this dimension is deliberately embedded in the artist’s visual program, the multiple perspectives emerging in Rugendas’ work inevitably challenge a universalizing anthropocentrism. This aspect is similarly evident in Teresa Margolles’ work, where situated in a setting of ruins, she also speaks to the need to reconsider the connections between humanity and its surroundings.

A humanity that interacts symbiotically with its environment raises a manifest challenge to the understanding of universal time, which, since the onset of the Modern Age, has been shaped by humanity’s rationalization of it7Lucian Hölscher, El descubrimiento del futuro (Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI, 2014).; time as we know it is a humanist configuration. When Rugendas portrays this Latin American humanity immersed in its environment, he is presenting an alternative approach to time. Thus, the human and non-human temporalities coexisting within the artist’s images reveal a scenario where there is neither transcendence of the human nor an anti-humanist critique, but rather the emergence of a posthuman8The posthuman is understood as a current of thought that “destabilizes the limits and symbolic boundaries posed by the notion of the human. Dualisms such as human/animal, human/machine and, more generally, non-human human are re-examined through a perspective that does not function on the basis of oppositional schemes”. Fracesca Ferrando, Posthumanismo filosófico (Segovia: Materia Oscura, 2023), 27. relationship with the environment, one that dissolves the dichotomies among the various entities Rugendas displays.

In observing these multiple temporalities, artistic visualizations gain fundamental value in the effort to reorganize today’s turbulent times. Didi-Huberman pointed out that they preserve an impurity of time that allows them to travel in directions that history cannot; in his words, “the history of images is a history of temporally impure, complex, overdetermined objects. It is a history of polychronic objects, heterochronic and anachronic objects”9Georges Didi-Huberman, Ante el tiempo. Historia del arte y anacronismo de las imágenes (Buenos Aires, Adriana Hidalgo Editora, 2011), 46.. Thus, when Margolles’ images overlap with those of Rugendas, we find that the Mexican artist also turns her gaze toward multiplicities of lives and connections with the environment that can only occur in a place like Latin America. And in a heterochronic manner, she also presents a subjectivity that operates on the same plane as its environment, this time, however, due to its own self-destruction.

The future is no longer what it used to be. At the beginning of the 19th century, as Rugendas traveled across the continent, it opened up as a possibility to imagine the future of emerging Latin American nations. According to Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, what the artist observed would later become the foundations upon which the countries he depicted were built. Today, however, those expectations for the times to come have been replaced by a future that collapses upon itself, as the risks of the present have effectively extinguished any possibilities of imagining a future beyond the present.

In this context, Teresa Margolles has stated10Aurora Villaseñor. “Teresa Margolles: las morgues como termómetro social.” Available in: https://gatopardo.com/arte-y-cultura/teresa-margolles-las-morgues-como-termometro-social/ that her interest in bodies devastated by violence dates back to the years she worked as a forensic technician in various morgues in Mexico. Between 1990 and 2007, the Mexican artist worked in such places; however, due to the escalating violence caused by cartels and organized crime, she decided in 2006 to go out into the streets. Through this practice, Margolles recognized that the battered bodies that arrived at the morgues were no longer distinguishable from those lying out in the open, scattered across the city. This led her to state on more than one occasion that “morgues are a social thermometer”11Ibídem.

During this period, when the streets progressively transformed into a vast open-air morgue, Margolles created one of her most recognized works: La Lengua (2000), an installation displaying a human tongue belonging to a young punk who had fallen victim to the street violence in Sinaloa. The way the artist presents violence speaks not only to its excess but also to the exposure of the human body as an utterly vulnerable entity, reduced to mere organic fragility—a condition that has been stripped of agency by a violence that has escaped human control.

Fig. 2. Teresa Margolles, La lengua, 2000.

At the 53rd Venice Biennale, curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina, Teresa Margolles exhibited ¿De qué otra cosa podríamos hablar? (What Else Could We Talk About?). For the occasion, she produced a series of installations reflecting on the violence wrought by organized crime from the perspective of battered bodies. This installation included a blanket soaked in blood from executions that had taken place near the northern border of Mexico, hoisted like a flag; audio recordings taken from locations of violent clashes between gangs; and an action in which floors and windows were cleaned with water mixed with blood obtained from the morgue. These gestures, recurrent in Margolles’ artistic project, recognize the human body in its most elemental organic materiality, once it has been deprived of any capacity to identify beyond the materialities that make up the body.

Fig. 3. Teresa Margolles, ¿De qué otra cosa podríamos hablar?, 2009.

When everything has been swept away by violence and life has been stripped of any attribute, the material remains of the body still persist. The way Margolles represents death and the raw reality of those battered bodies highlights the basic agency of organisms. This last remnant of humanity points to a way of relating to time not dissimilar to that of animals or plants; its fragile finitude does not correlate with the social temporalities that humanity has constructed for itself.

The liminal space occupied by the images of Margolles and Rugendas is built upon more fluid and dynamic visions of identities and existences; whether through the multiple connections between entities cohabiting the depicted landscapes or the emphasis on the organic materiality of bodies, both projects challenge the hegemony of an anthropocentric, linear time. These perspectives suggest other temporalities and forms of relationship with the passage of time, but they also allow us to envision other potential worlds, where the human is not the sole parameter for relating to the world.

3. Raw flesh, dead flesh

In An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter (2000), César Aira’s novelized account of Mauricio Rugendas’ life, the Argentine writer focuses on a tragic accident the German painter suffered in 1837 while crossing the Andes. After a brief stay in La Serena, Rugendas set out for Buenos Aires to continue his quest for natural and traditional scenes to depict. His journey was abruptly interrupted when his horse, startled by the sudden sight of a mule’s corpse, reared up, causing him to fall. His companion, fellow painter Robert Krause, who accompanied him on this journey, would later describe the accident as follows:

El caballo se había asustado ante el cadáver de una mula, dando un violento respingo y encabritándose. Se rompieron las cinchas, de modo que Rugendas necesariamente tuvo que caer con la montura. Posiblemente, el caballo había tropezado también con una de las muchas raices que precisamente en aquel sitio cubrían y cruzaban el camino, cayendo con el jinete12Robert Krause, “Travesía de los Andes y estada en Mendoza en el año de 1838. Diario íntimo del paisajista alemán”, Phoenix, n° 2-4 (1923): 42-46..

The injuries caused by the accident rendered him unable to continue his journey, keeping him bedridden for two months in the city of Mendoza. The severity of these injuries left him with lasting effects for the rest of his life.

In Aira’s novel, the fictionalized Rugendas also experiences a traumatic event, but with somewhat different consequences. In the novel, it is not the sudden appearance of a mule’s corpse that startles the horse and causes the tragic accident, but rather a lightning bolt that capriciously strikes the painter’s head during a storm, completely disfiguring his face. To avoid the uncomfortable stares directed at his deformed face, the fictional painter decides to cover it with a veil, developing a new way of seeing the world. This veiled reality comes to redefine how the painter perceives the world, completely altering the images he will later produce. Through this subtle gesture, Aira takes a reflection on vision to the extreme, suggesting that every image is constructed from a point of view, which is never passive.

The gaze is always situated and particular, making it a practice of complete vulnerability; today’s gaze is not the same as tomorrow’s, and therein lies the value of the landscape as a testament to a particular gaze. Parallel to this, the constant flux of nature makes any attempt to apprehend it appear as an irreproducible snapshot, possible only through the convergence of multiple dynamic assemblages in its appreciation. On this aspect of nature, Manuel DeLanda remarked that humanity’s supposed permanence throughout history is nothing more than an “organic chauvinism” that disregards its metamorphic character13Manuel Delanda, Mil años de historia no lineal (Barcelona: Gedisa, 2011), 127..

When Rugendas and Margolles lift their gaze to observe their surroundings, the first response is not from the human gaze but rather the knowing gaze of the animal. The return of the gaze by nature, made through the animal’s eyes, marks the point of connection between these two entities, both too mutable to maintain a sustained dialogue. Thus, any questioning of the relationships between the various entities inhabiting the imaginary of Rugendas and Margolles begins with this initial animal gaze.

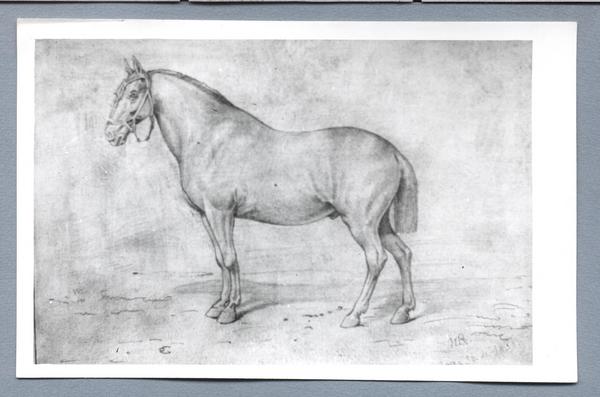

Rugendas’ early works focused on the representation of landscapes and horses, an animal that fascinated the painter, inspiring countless sketches during his early period14Gertrud Richert, “Johan Moritz Rugendas. Un pintor alemán en Ibero-América”, Anales de la Universidad de Chile (1960): 311–353.. Likewise, Teresa Margolles’ initial works with the SEMEFO Group15Collective funded by Carlo López, Teresa Margolles and Arturo Angulo in 1990. also centered on animal corporeality, particularly that of horses, which stood at the forefront of the violence unleashed by organized crime. Seen as a central part of the organic network of nature, the animal emphasizes humanity’s particular relationship with its environment, its gaze serving as the liminal space between humanity and nature, the point of connection. Jacques Derrida highlighted this notion, saying:

That gaze so-called “animal” makes me see the abyssal boundary of the human: the inhuman or ahuman, the end of man, where man dares to announce himself, calling himself that way by the name he thinks he gives himself16Jacques Derrida, El animal que luego estoy si(gui)endo (Madrid: Trotta, 2008), 28..

The animal’s otherness is challenged by its gaze, which brings it uncannily closer to the human, making it as though the human gaze observes itself in another’s eyes. In this sense, the animal is not merely an affirmation of the privileged place that human subjectivity has designated for itself but rather highlights an interconnection where there is no animality without humanity, but neither humanity without animality. In the Latin American context, this is expressed as the manifestation of an ongoing dialogue. Therefore, the remarkable coincidence in the early works of Margolles and Rugendas marks the paths that their respective works would later follow, evolving to raise questions of identity.

Fig. 4. Mauricio Rugendas, Caballo no identificado, c. 1802-1858.

The instinctive equestrian representations Rugendas developed in his early sketches not only fueled his clear interest in nature but also influenced the recurring presence of animality in his work. In this sense, rather than serving as experimental material, animals became a hallmark of the painter, as described by Gertrud Richert:

Particular attention should be given to the fondness with which he devoted himself to animals in Chile—not only to his beloved horses but also to bulls, cows, donkeys, goats, sheep, in short, all the animals he observed and studied on the estates where he was welcomed. He represented these animals conscientiously, with his masterful realism and accuracy17Gertrud Richert, “Johan Moritz Rugendas In Chile” in J. M. Rugendas en Chile (Prestel-Verlag: s/e, 1959). Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name..

Rugendas used animals to specify where his scenes were set, but equally, to characterize the dynamics people established with their environment. Thus, for the painter, animality—as an integral part of a broader nature—was also appreciated without prejudice, suggesting that on many occasions it was not entirely subject to human will. Rather, it enabled its own appearance, interacting in complex ways with its surroundings and humans alike. Derrida described this peculiar impulse sparked by the animal gaze as follows: “under the animal’s gaze, anything can happen to me; I am like a child ready for the apocalypse, I am the apocalypse itself, that is, the last and first event of the end, the revelation, and the verdict”18Ibid., 28.. Rugendas both seeks and is sought by the animal’s gaze; his illustrations do not show animals as mere accessories to the landscape but as beings with their own agency, a circumstance that could only be perceived thanks to the artist’s contemplative gaze.

In 1994, Teresa Margolles, together with the SEMEFO collective, embarked on an investigation that led them to locate the clandestine slaughterhouse supplying horse meat to various places in Mexico City. There, they obtained a horse, a mare, a mule, hides, horse heads, and various bodies of fetuses and unborn foals19Daniela Merediz. “Transgrediendo al espectador: Colectivo SEMEFO”. Available in: https://archivochurubusco.encrym.edu.mx/n3letras2.html. With these materials, the artistic collective organized the exhibition Lavatio Corporis at the Carrillo Gil Art Museum. In this exhibition, they created a series of installations displaying these bodies and dissected limbs. The most ambitious installation was Carrusel Lavatio Corporis, which, emulating a children’s carousel, consisted of five unborn foals suspended by chains around a circular metal structure. On the base platform, beneath the animals, emerged large nails pointing toward the levitating corpses.

Fig. 5. Grupo SEMEFO, Carrusel Lavatio Corporis

The violence enacted by the project extends beyond mere representation. The collective stated that their proposal does not operate in the same way as the fantastical and quasi-parodic violence of cinematic gore, as their working materials are the everyday residues left by violence. Moreover, the exhibition leaflet noted, “SEMEFO uses elements that have been violently abused on a daily basis, almost imperceptibly, but always present”20Lorena Wolffer. “Construyendo mitos: El performance en México”. Available in: https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=11444. The collective’s reclamation of these objects and materials from daily life operates as an act of restoring agency to the bodies and materials stripped by the ferocity of violence.

The relentless violence portrayed in SEMEFO’s work and later in Teresa Margolles’ work serves as an equalizer among the entities that suffer it. The fragility of organisms, noted earlier, demands that violence be understood from a post-organic perspective—that is, from a viewpoint that considers it as something caused by humanity but which transcends human nature, multiplying its victims and challenging the very concept of humanity, as Hannah Arendt pointed out. This circumstance invites us to consider possibilities that go beyond safeguarding humanity alone, extending protection to all entities affected by violence.

Fig. 6. Grupo SEMEFO. Available in: Archivo Churubusco.

The dehumanized body is the clearest material expression of the equalizing effect of violence. The way Margolles displays the tongue in the aforementioned installation, La Lengua, is by mounting it on a small metal stand. The same mounting technique was used years earlier with the horse fetuses displayed in Lavatio Corporis, which were also exhibited on large metal stands. The dehumanization of the bodies affected by violence shows the same fate that animal bodies and nature suffer when exposed to such treatment; the outcome is always the same in all cases. In this regard, the Mexican artist’s work is a warning to redefine all boundaries that violence, catastrophically, causes to explode.

Just as the animal’s gaze establishes a point of contact with humanity, the animal corpse complicates any categorization or territorialization one might make of it. Gabriel Giorgi states, “the corpse, in its very materiality, is a point of excess that resists the rhetoric of the personal, the proprietary, the human”21Gabriel Giorgi, Formas comunes. Animalidad, cultura, biopolítica (Buenos Aires: Eterna cadencia, 2014), 114. Thus, if the animal’s gaze reflects a displaced constitution of humanity, the absent gaze of the corpse materializes this displacement. To try to grasp animal death demands stripping away any cultural pretense of sanctifying death; that body lying lifeless does so just as a human corpse would, yet it is not human.

It is not surprising, then, that visitors’ reactions to Lavatio Corporis focused on their rejection of the graphic display of animal corpses as mere objects.

This work generated such a significant impact—presenting corpses in a graphic way, breaking the rules, showing all those things that one does not want to see in a museum—that some visitors felt unwell, not only because of the smell but also due to the sight of animals displayed as objects of torture22Daniela Merediz. “Transgrediendo al espectador: Colectivo SEMEFO”. Available in: https://archivochurubusco.encrym.edu.mx/n3letras2.html.

The rejection provoked by SEMEFO’s exhibition represents the crux of the dual pull of attraction and repulsion exerted by the animal.

The animal issue in Margolles and Rugendas is intertwined with the gaze. Their work shapes their respective imaginaries and proposes the reading of a displaced humanity. The animal in Rugendas’ work is the invisible thread that integrally connects the various entities he observes in his landscapes. In Margolles’ work, this conciliatory role of the animal turns into a demand as it transforms into a corpse. The juxtaposition of their images reveals two sides of the same coin that, in both living and dead flesh, lays out potential paths on which to travel.

4. Like chroniclers, like landscape painters

The meticulous detail with which the projects of Margolles and Rugendas depict the various geographies surrounding them has led them to be recurrently designated as cartographers, even more than as artists. Sarmiento described the German painter by saying, “Rugendas is a historian rather than a landscape painter; his paintings are documents… Humboldt with the pen and Rugendas with the pencil are the two Europeans who have most vividly described America”23Rafael Sagredo, “El ilustrador de Claudio Gay”, in Rugendas en la República (Santiago de Chile: Centro de Estudios Públicos, 2023), 94.. Similarly, Margolles’ explicit representation of violence has also been interpreted as a map of reality. However, this characteristic is precisely what ultimately distances these projects from cartographic abstraction.

In the micro-story On Exactitude in Science (1946), Borges tells of an empire that, obsessed with cartographic sciences, demanded its cartographers create a map of the city, at a 1:1 scale, that matched its dimensions exactly. As expected, the oversized map proved useless. Toward the end of the story, Borges describes the end of this practice by saying, “Later generations, less attuned to the study of Cartography, understood that this sprawling map was useless and, not without some pity, left it exposed to the harshness of sun and winters. In the western deserts, tattered remnants of the map lingered, inhabited by animals and beggars”24Jorge Luis Borges, “Del rigor en la ciencia”, in El hacedor (Madrid: Debolsillo, 2011), 45.. In contrast, the persistence in capturing a unique moment is what has enabled the vitality and constant renewal of Margolles and Rugendas’ proposals, preventing them from ending up as scattered ruins in the desert.

For this reason, abstraction holds a marginal place in the work of both artists; rather than representing the world, their projects seek to present it. Their gaze is that of the flâneur or the witness who roams and experiences their surroundings—not one who tries to explain it at all costs. This situated way of observing the territory causes the horizon to unfold in their eyes, not the map. This subtle shift from a top-down gaze (cartography) to a horizontal one (landscape) radically changes the subjective relationship with what is to be depicted. Speaking about this non-schematic presentation of the landscape, Boehm noted:

The logic of the horizon is, by contrast, entirely alien to cartography. Its natural representation is measured by an imaginary eye, aloft, that traverses terrain laid out in a grid. Undoubtedly, the journey from schematic T-maps created in the Middle Ages to accurate projections of the Earth, all based on schematic premises, was long and difficult25Gottfried Boehm, Cómo generan sentido las imágenes: el poder del mostrar (Ciudad de México: Libros UNAM, 2017), 94..

Therefore, when viewing both projects’ images side by side, we observe a particular relationship between the Latin American natural environment—and, by extension, the landscape—and the bodies that inhabit it. Consequently, if “maps deal with the world beneath our feet, while landscape deals with the world rising before us”26Ibid., 96., then the distinctive strength of landscape lies in its ability to display the multiple entities inhabiting it, including those that the abstraction of human thought might overlook.

Rugendas’ creation of costumbrista (depicting local customs) images is not merely an acknowledgment of what he perceived in those rural scenes but, above all, the articulation of a socio-cultural power underpinning the identity of nascent republics. As noted earlier, these images speak to a stage where there was still an entire future to be shaped. In contrast, the landscape found in Margolles’ work no longer shows a future open for writing; rather, the horizon, in addition to being uncertain, has been stripped of any possibility of imagining it differently from the present. What kind of future could there be when violence has become so embedded in everyday life that it has turned into the horizon of meaning?

In the painting Argentine Gauchos and Wild Horses (1846), Rugendas creates one of his most intriguing works. The image’s power lies in its triangular composition, guiding the gaze from the base to the peak, while the center of interest is highlighted by the light illuminating this area. As we trace back along this compositional path, we notice that the boundaries of bodies progressively blend together; the horses, the gauchos, and the hill subtly become one. In this sense, the horses are not merely passive elements in the scene; rather, their prominent position shapes the scene while simultaneously being shaped by it

Fig. 7. Mauricio Rugendas, Gauchos argentinos y caballos salvajes, 1846.

The integrated nature proposed by Rugendas, as Pablo Diener and María Fátima Costa observe, is made possible thanks to the naturalist influence the painter received. In his work, “the influence of Humboldt is clearly visible, and through him, also that of Goethe, who conceived nature as a totality and an organic intertwining of topography, flora, fauna, and human life”27Pablo Diener and María Fátima Costa, Rugendas 1802-1858 (Augsburgo: Goethe Institute, 1998), 35., which can only be perceived from the perspective of a landscape painter actively interacting with their environment.

Thus, Rugendas’ project reconciles the naturalist approach with Romanticism’s influence. The balanced fusion of these aspects ultimately shapes the particular exploratory methodology behind Rugendas’ pictorial practice, allowing him to observe the relationship between the Latin American territory and its inhabitants. In this sense, the displaced humanity that the German painter encountered on the continent parallels his own approach to the world, questioning humanity’s place within it.

Beyond the articulation of diverse entities within the landscape that Rugendas proposes, the inescapable perspective from which he constructs it makes these images an inherently human approach. As previously noted, the practice of landscape serves as a strategy to observe the world in a less abstract way, highlighting the multitude of entities that compose it. Regarding this presentation of the landscape, in Appendix on the Limit at the Horizon, part of Notes for an Imaginary Cartography of the Fjords (2024) by Emilia Pequeño, it is noted:

[…]

el horizonte es humano y por lo tanto

se mueve con nosotros

como la sombra

es preciso pensarlo

más allá de un límite o frontera arrobada sobre sí misma

un lugar de contacto

entre cuerpos subyacente

a distintos estados de la materia

la membrana y la seda se funden

esgrimiendo derechos propios

en una lejanía naciente

todo límite puede entonces

pensarse desde ahí

como roce de una nube sobre la línea del mar28Emila Pequeño Roessler, Notas para una cartografía imaginaria de los fiordos (Madrid, Vaso Roto Ediciones, 2024), 61

Landscape is a framing of the liminal space that defines what belongs to it and what is foreign, encouraging the merging of lines at the horizon. Geographic, social, bodily, and life-and-death boundaries, as well as the boundaries within art itself, appear consistently throughout Teresa Margolles’ work, crystallized through landscape. The artist delves into spaces disrupted by violence, capturing in landscape form the various modulations of the observed boundaries.

In 2020, the Mexican artist held an exhibition titled La Piedra at Es Baluard Museu in Mallorca. For this occasion, she displayed photographs and installations that emerged from her time in Cúcuta, a city on the border between Colombia and Venezuela. Initiated in 2017, this project explored the socio-economic dynamics experienced and endured by those living in this border territory, which ultimately reflected the issues that sparked the subsequent humanitarian crisis and mass migrations from Venezuela. In the photograph Carretillas sobre el Puente Internacional Simón Bolívar (2017), Margolles portrayed 17 women engaged in trochera labor—transporting illegal goods across the bridge. The urban landscape in the photograph shows each woman holding a wheelbarrow, an object reminiscent of better times, when the loads weren’t illegal goods but essential food items or other necessities.

Fig. 8. Teresa Margolles, Carretillas sobre el puente internacional Simón Bolívar, 2017.

In the catalog for this exhibition, Imma Prieto describes the reality faced by these women, stating that “their stories carry echoes and sighs, desires and reality, but, above all, strength—a fierce will to carry on”29Imma Prieto, La piedra (Mallorca: Es Baluard Museu, 2020). Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name., a determination that Teresa Margolles intuitively pursued throughout the project, finally capturing it in this photographic series. In it, a simple wheelbarrow represents not only a past better than the present but also the hope for a brighter future.

The horizon-focused gaze proposed by Margolles and Rugendas’ works allows us to observe the depth of a reality, in both plastic and narrative terms. With their feet on the ground, their horizon doesn’t end at the ground—as would be the case for a cartographer—but extends as far as the gaze allows. Presenting reality in this way raises the question of what happened in the precise moment after it was captured. What these artists put into images is only a starting point, projecting into a latent future.

5. Exit

Towards the end of his journey through Latin America, during his stay in Peru between 1842 and 1845, fascinated by local customs, Rugendas began to paint “las tapaditas”; Lima women who dressed in the traditional saya and manto, an outfit that only left one eye visible and was popular in viceroyal and republican Lima. This gesture would later serve Aira in the creation of his Rugendas Velado. The tapaditas observed the world through a peephole, that is, a timid gaze that observes but does not allow itself to be observed, where the image is constructed in a counter-hegemonic way; those who looked through the veil saw an uncomfortable but latent reality, which explains the discomfort this fashion caused among the clergy of the time: “The use of women walking covered has reached such an extreme that it has resulted in great offenses to God and notable harm to the republic, because that form does not allow a father to recognize his daughter, a husband his wife, nor a brother his sister”30Antonio De León Pinelo, Velos antiguos y modernos en los rostros de las mujeres: sus conveniencias y daños (Madrid: por Iuan Sanchez, 1641) 235. In other words, a hidden gaze that saw what everyone else saw, but not in the way that others expected.

The project of Teresa Margolles, in this sense, is not about seeking to return to a state prior to devastation, but rather “seeks a place to generate a counter-image that manages to question the authority and legitimacy of the official image”31María Inés Rodríguez, catalogue of El testigo, 2010, 18., hence the need to subtly intrude into the territories to be explored. For his part, Rugendas, as described, avoided the imposition of ideas over images; in his words, “I placed the greatest effort into faithfully reproducing nature. And I never sacrificed truth for the sake of effects”32Pablo Diener and María de Fátima Costa, Rugendas e o Brasil (Río de Janeiro: Capivara, 2023), 39.. The timid and exploratory way in which both artists observed the world is not only a methodological principle that unites them, but above all, it is a resource for perceiving the environment differently. An invitation to see the world with expectancy and to wait for the gaze it will return to us.

Bibliography

Aira, César. Un episodio en la vida del pintor viajero. Madrid: Literatura Random House, 2015.

Attali, Jacques. Historias del tiempo. Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004.

Bindis, Ricardo. I El despertar de la pintura en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Lord Cochrane Ediciones, 1979.

Boehm, Gottfried. Cómo generan sentido las imágenes: el poder del mostrar. Ciudad de México: Libros UNAM, 2017.

Borges, Jorge Luis. El hacedor. Madrid: Debolsillo, 2011.

Delanda, Manuel. Mil años de historia no lineal. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2011.

De León Pinelo, Antonio. Velos antiguos y modernos en los rostros de las mujeres: sus conveniencias y daños. Madrid: por Iuan Sanchez, 1641.

Derrida, Jacques. El animal que luego estoy si(gui)endo. Madrid: Trotta, 2008.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Ante el tiempo. Historia del arte y anacronismo de las imágenes. Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo Editora, 2011

Diener, Pablo. Rugendas 1802-1858. Augsburgo: Goethe Institute, 1998.

Diener, Pablo y Maria de Fátima Costa. Rugendas e o Brasil. Río de Janeiro: Capivara, 2023

Ferrando, Francesca. Posthumcanismo filosófico. Segovia: Materia Oscura, 2023.

Giorgi, Gabriel. Formas comunes. Animalidad, cultura, biopolítica. Buenos Aires: Eterna Cadencia, 2014.

Hernández, Miguel Ángel. “Prólogo. La historia del arte y el tiempo de la escritura”. In El tiempo de lo visual. La imagen en la historia, by Keith Moxey. Bilbao: Sans Soleil, 2015.

Hölscher, Lucian. El descubrimiento del futuro. Madrid: Siglo XXI, 2014.

Krause, Robert. “Travesía de los Andes y estada en Mendoza en el año de 1838. Diario íntimo del paisajista alemán”. Phoenix, n° 2-4 (1923), pp. 42-46.

Merediz, Daniela. “Transgrediendo al espectador: Colectivo SEMEFO”. Revista Archivo Churubusco, s/f. Available in: https://archivochurubusco.encrym.edu.mx/n3letras2.html

Pequeño, Emilia. Notas para una cartografía imaginaria de los fiordos. Madrid: Vaso Roto Ediciones, 2024.

Prieto, Imma. La piedra. Mallorca: Es Baluard Museu, 2020. Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name.

Richert, Gertrud. “Johan Moritz Rugendas. Un pintor alemán en Ibero-América”. Anales de la Universidad de Chile, 1960: 311–353.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. Oprimidos pero no vencidos. La Paz: La mirada salvaje, 2010.

Rodríguez, María Inés. El testigo. Madrid: CA2M, 2014. Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name.

Villaseñor, Aurora. “Teresa Margolles: las morgues como termómetro social”. Revista Gatopardo, 21 de julio del 2020. Available in: https://gatopardo.com/arte-y-cultura/teresa-margolles-las-morgues-como-termometro-social/

- AA. J. M. Rugendas en Chile. Prestel-Verlag: s/e, 1959. Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name.

- AA. Rugendas en la República. Santiago de Chile: Centro de Estudios Públicos, 2023.

Wolffer, Lorena. “Construyendo mitos: El performance en México”. Revista Nexos, 1 de marzo del 2015. Available in: https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=11444