All order, all discourse, that aligns with capitalism leaves aside, my friends, what we will simply call matters of love.

-J. Lacan

The wall of my destiny.

-T. Bernhard

“During the military coup, there were terrible rumors that our friends, the disappeared detainees, might not only be in the barracks; they might also be in psychiatric hospitals. I decided to go”1“Interview with Paz Errázuriz, special guest to the 2015 Venezia Biennale, by Valentina Montero”, Santiago: Atlas. Revista de fotografía e imagen (November 2014).This is how Paz Errázuriz recalls her first encounters with the world of confinement and madness, and perhaps it was this desperate search that ultimately defined her own artistic ethics. Photography, she once said, only matters if it becomes a “life detector.” Over some forty years, Errázuriz became accustomed to living among others —prostitutes, the blind, the insane, transvestites, boxers, circus performers, tango dancers, the Kawésqar, immigrants— and in that sense, her photographs are less an image than a question, as complex and contemporary as the issue of how to live together.

In the early 1990s, Errázuriz decided to visit a psychiatric institution again. This time, it was an old sanatorium for tuberculosis patients located in the foothills of the central region of Chile, now converted into an asylum where men, women, and children live together. She rented a small cabin a few kilometers from the site, although sometimes, not without fear of the inmates’ piercing screams, reminiscent of a locomotive’s whistle, she stayed in one of the hospital’s rooms. From that stay, and from Diamela Eltit’s desire to write about and think through the images Errázuriz had accumulated as if they were frames extracted from the fabric of her own experience, El infarto del alma (1994) was born.

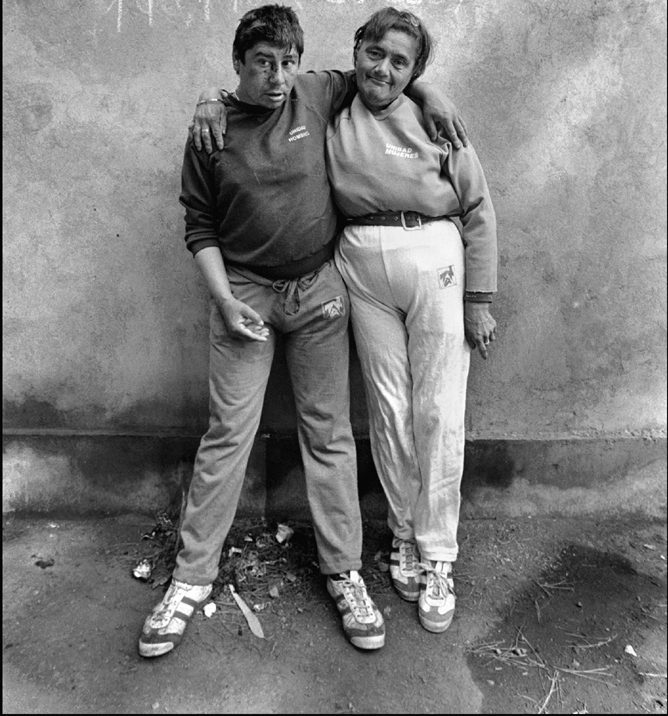

Figs. 1 y 2. Paz Errázuriz, El Infarto del Alma, 1992

Es sabida la curiosidad social que desarrolló cierto tipo de fotografía documental, sobre todo a la hora de hurgar en la vida de los pobres, los miserables, los freaks sociales, todos aquellos que, como decía el cineasta Eduardo Coutinho —otro artista que supo oler “la emulsión sulfúrica de la historia”—, no tienen nada que perder2George Didi-Huberman, “Cine, ensayo, poema. La Rabbia, de Pier Paolo Pasolini”, El jardín de los poetas. Revista de teoría y crítica de poesía latinoamericana 3, (2016). Y son conocidas, también, las alertas que esa intromisión en el dolor de los demás encendió, sobre todo si las imágenes, en su afán por denunciar las injusticias del mundo, quedaban adheridas a un repertorio de palabras provenientes mucho más del amor propio que del deseo de otro: empatía, sentimentalismo, mimetismo caritativo, paternalismo epistemológico, humanitarismo. No hay bondad que pueda curar el daño.

It is well known the social curiosity developed by a certain type of documentary photography, especially when delving into the lives of the poor, the wretched, the social freaks—all those who, as filmmaker Eduardo Coutinho (another artist who knew how to smell “the sulfurous emulsion of history”) put it, have nothing to lose3George Didi-Huberman, “Cine, ensayo, poema. La Rabbia, de Pier Paolo Pasolini”, El jardín de los poetas. Revista de teoría y crítica de poesía latinoamericana 3, (2016). And it is also known, the warnings that such intrusion into the pain of others triggered, especially if the images, in their eagerness to denounce the world’s injustices, adhered to a repertoire of words stemming much more from self-love than from desire for another: empathy, sentimentalism, charitable mimicry, epistemological paternalism, humanitarianism. There is no kindness that can heal the damage.

Regarding these dilemmas, in 2003 Susan Sontag published a text, Regarding the Pain of Others, on the relationship between photography and death produced with cruelty, between photography and war. Reflecting on the dual powers that photographic images may hold —photography as a social document and photography as art— she warns about the tension between these two forms of visual discourse, one aiming to mortify emotions (pity, compassion, outrage), and the other to turn into aesthetics, into sublime, astonishing, or tragic renditions of beauty, that which is of the order of calamity. “What does one do with the knowledge that photographs bring of distant suffering?” Sontag asks. What is to be done, especially today, when the images that shape the world’s sorrow are the “repugnant appetizer [with which man] waters his morning meal”?4Susan Sontag, Ante el dolor de los demás (Buenos Aires: Alfaguara, 2003), 36

The photographs that make up El infarto del alma are not, strictly speaking, representations of madness, but rather the place where illness ceases to be a raw material laid out to be observed, as Charcot’s one-eyed gaze observed the poses of hysterics to cast upon them the scalpel of his medical knowledge. Not a raw material to be looked at, but the point at which the camera can only bear witness to the encounter with an unprecedented body —every body is— that demands an incipient, minimal, modest aesthetic thickness that we will call here reading. In this sense, Errázuriz resembles more a psychoanalyst than a social photographer, for she knows that if the body is sick, it is sick with meaning, and that reading it is to dissolve its clichés and open oneself to the unexpected. To read, not to look. To read to crack the parapets embedded in sight. Perhaps that is why every time Paz Errázuriz is asked about her working procedures, the first word she mentions is reading. Reading is not seeing, or at least it is a way of seeing that does not bend to the demand for clarity and revelation.

Therefore, in front of these photographs, “forensic spectators, voyeurs, or connoisseurs of eccentricities” will be disappointed. If what we see is the trace of the encounter with an unprecedented body, it is because Errázuriz avoids a series of formal devices that turn the other into an impudent fairground attraction. These are black-and-white photographs that, in their chromatic modesty, dodge an overdose of realism; they are photographs that avoid the contrivance of close-ups, which intensify gestures and leave our morbid gaze fixated on the rotten tooth, the wild eye, the disproportionate and battered body, the skin punished by cold and violence; they are photographs indifferent to the glory of the decisive moment, crafted more from an iconic chastity that puts obstacles in the way of consumable images of madness.

We said that the photographs in El infarto del alma are not strictly images of madness, because madness is not something that can pass through a developer tank and come out as an image, and if it were, then madness would no longer be there. For this very reason, because it is ungraspable, we ceaselessly inquire about it. And that is what Paz Errázuriz does with her photos: she offers them as a space of hospitality that accepts the arrival of a strange body without casting a taxonomic sanction upon it, but rather exploring what happens between one body and another, including her own, including ours. And what is here this strange body? No longer madness but love. Of the thirty-eight photographs that make up the book, thirty-five depict couples formed in confinement. Most pose for the camera, as if in that ritual of immobility of the photographed subject, in that display of artifice and staging, in that almost identical treatment given to the portrayed bodies, Errázuriz would find a way to avoid shrinking the distances to the point of merging with her lovers. And not out of indifference, elitism, or self-imposed emotional limitation, but because it is the fairest way to approach love. There is no harmonious conjunction between the sexes, just as there is none in the relationship with others, there is no relationship without pathos and pain, without unease and uncertainty, says Alexandra Kohan, and El infarto del alma leaves that gap intact, not seeking to manage it through the idealization or sanctioning of madness or love 5Alexandra Kohan, Psicoanálisis. Por una erótica contra natura (Buenos Aires: Indie libros, 2019).

Turning the other into an object of knowledge, a raw material for theory building, or a place to corroborate truths constructed through power is part of the “ideological abuse” that institutions like psychiatric hospitals have been practicing for a long time, even with sexuality. In the photographs of El infarto del alma, bodies seem to emerge from the silence, completely indifferent to the pacts between anatomy and sexuality, open to the amorous experience that is not here the same as sexuality. That vague mist is dissipated by the Institution, intent on maintaining stereotypes: in white sweatshirts, those who belong to the “women’s unit”; in black, those who belong to the “men’s unit.” Sexuality reduced to genitality again and again, even there, in the heart of abandonment, where the outside world drifts farther and farther away, where everything seems to have been lost, except being there.

How big is the world of confinement? How big is the brutal and unconscious world of the so-called sane? Thinking is not the same as knowing. Of the couples who embrace, hold hands, touch, share a cigarette, smile, lie in bed, undress, we know only those gestures born of bodies abandoned to the small and the scant. So El infarto del alma is not strictly a book about love, but about that horizontal and democratic game that gestures often are. If what connects love and madness is the subordination to a universal discourse that dismisses the error and surprise produced by the unknown, Paz Errázuriz’s photographs make us see not the strange, but the most familiar: those gestures that embody the desire to cling to life despite everything. This is what those tender and fragile gestures of those condemned to confinement speak to us. And in this way, Errázuriz’s images also transform, into a small pile of accumulated love in the corner of a devastating and mortal world.

El infarto del alma ends with three photographs. One shows a hospital corridor with several windows and walls and ceilings completely peeled off; another, a staircase located in a rather gloomy corner; and the last, a double hallway where we see a man walking away from the viewer, another sitting with his bare feet staring into space, and another lying on the floor, of whom we only see his torso and head. Three images of solitary men, three images where nothing happens, as if those bodies clinging to one another that we saw on previous pages had been nothing more than a small dream. The sadness of these images, the cold they emit, the desolation they invoke, is perhaps the way Paz Errázuriz found to cool down empathy or compassion, a type of affection that, as Luciano Lutereau says, is always an identification with the suffering of the other that is fusional and narcissistic. It is different, instead, to endure the pain of the other, because there, in “that part of the other’s suffering that cannot be suffered, dialogue begins”6Luciano Lutereau in Instagram @lucianolutereau.