Opening

The circulation of visual culture in Latin America is a complex and often controversial phenomenon that involves dynamics of power, cultural appropriation and resignification of historical narratives. Through museological studies, it is possible to analyze how museum institutions have functioned both as tools of cultural legitimization and exclusion of certain discourses and representations. This paper examines the role of museums in the diffusion and legitimization of images and objects, and their effects on the public perception of visual culture in Latin America, establishing a dialogue between two artistic works that, directly or indirectly, criticize museum spaces and their role in the circulation of visual culture: Proyecto LiMAC (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima, 2002) by Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra Helsinki and Cuerpos Blandos (1969) by Chilean artist Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña.

From artistic modernity in Latin America to contemporary postcolonial reflections, artists have questioned and subverted the norms and dynamics of power that legitimize and disseminate images in museums, which in turn are defined within the circulation of visual culture, considering that history is anchored to “what can be seen” and its methods of circulation in the spaces of the gaze, along with the analysis of the interrelation between images and power1Carla Pinochet Cobos, Derivas críticas del museo en América Latina, Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI Editores, 2014.. The aforementioned works reflect on the museum as a physical institutional structure and as a space of discursive definition, establishing a link that, despite being forty years apart, works as a museum disruption that questions what is and what belongs to a museum.

The National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA) in Santiago was inaugurated on the occasion of the centennial of the first National Government Junta of Chile (1910) and, in its early years, was housed in the National Congress2The National Museum of Fine Arts of Chile was founded on September 18, 1880 under the name of National Museum of Paintings and was located in the upper floors of the National Congress until 1887. In that year, due to incompatibility with legislative activities, the museum moved to the building known as the “Parthenon” in the Quinta Normal de Agricultura. This change of venue preceded the official founding of the MNBA in 1910, when the current Palacio de Bellas Artes in Parque Forestal was inaugurated. See “Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Antecedentes de las colecciones del MNBA”, Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio, accessed June 10, 2025: https://www.mnba.gob.cl/antecedentes-de-las-colecciones-del-mnba-0. It is the ultimate expression of cultural nationalism or what many theorists of critical museology would call a “museum mausoleum”3Theodor W. Adorno, Prismas: la crítica de la cultura y la sociedad, trad. Manuel Sacristán, Barcelona: Ariel, 1962, 187. The MNBA is a space in dispute: while authors like Carla Pinochet consider it cold4Carla Pinochet Cobos, Derivas críticas del museo en América Latina, Ciudad de México: TOMA, 2021, 27–30., the most conservative art lovers are outraged by the absence of framing5The exhibition “Luchas por el arte” (MNBA, 2022) presented works stripped of their original frames, in order to re-signify them as open and disputed archives. Curators Gloria Cortés and Eva Cancino explained that the frames acted as devices of authority and interpretation that they wished to deactivate. This decision generated controversy among conservative sectors of the public and art critics. See Paula Valles, “¿Sacaron los marcos de los cuadros por ‘apatronados’? En el Bellas Artes, la verdad tras una declaración polémica” Culto – La Tercera, April 24, 2024: https://www.latercera.com/culto/2024/04/24/sacaron-los-marcos-de-los-cuadros-por-apatronados-en-el-bellas-artes-la-verdad-tras-una-declaracion-polemica. Langlois understood this battlefield very well and, fifty years ago, created a work that literally exceeds the museum space, connecting the inside with the outside. In October 1969 he made the intervention Cuerpos blandos (Soft Bodies), at the invitation of Nemesio Antúnez, then curator of the MNBA, with the aim of modernizing the museum. The work consisted of 200 meters of plastic sleeves filled with newspaper that ran through the museum, through windows and connected with the exterior. This ephemeral and precarious material reflected a deliberate intention to reject monumentality and the traditional values of art. Shortly after being mounted, the work was replaced and stored in the museum’s storeroom along with other works, mainly imitations of classical statues.

Paul Preciado describes how, contrary to what cultural theorists tend to think, the museum is in constant dialogue with its territory, being a co-constructive space that is constituted from the audience and the space, and not the other way around6Paul Preciado, El museo apagado. Pornografía, arquitectura, neoliberalismo y museos, Buenos Aires: Fundación MALBA, 2017, 34-36.. The excess seen in this polyurethane work by Langlois speaks to these processes and makes an imaginative effort that goes against the mainstream of the art of its time. The work frees itself from the “property” granted to it by the museum and becomes a living testimony, breaking with the formal and material conventions of art and questioning, in turn, the rigidity and norms of museum exhibition. According to Javiera Bagnara Letelier, Langlois exposes the arbitrariness of established artistic hierarchies, proposing a work that, in its apparent banality, dismantles the pretensions of the museum as a neutral space7Javiera Bagnara Letelier, Boletín Nº9 Juan Pablo Langlois, Santiago: Fundación CEdA, 2021.. This work is representative of a modern critique (generating a break towards the contemporary) of the institutionality of art in Latin America, where the museum is presented as a space of power that defines what is culturally valued and what does or does not enter the historical canon.

Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña with Cuerpos Blandos (1969). Courtesy of his personal Archive administered by the Nemesio Antúnez Foundation.

While thinkers such as Paul Valéry allude to the mortuary shelter that museums produce8Paul Valéry, Le problème des musées (1923), cited in Piezas sobre arte, Madrid: Visor, 2005, 105-107., philosophers such as Peter Sloterdijk underline the effects that these spaces have on visitors: fatigue, yawning and apnea are common symptoms of those who enter a museum, whose immediate impulse is to seek the end of the tour to finish the visit9Peter Sloterdijk, Esferas I: Burbujas, Madrid: Siruela, 2014, 55. Museums build interiors that magnetize pieces and repel visitors. It is not strange, from these perspectives, that this experience is avoided and that it is constructed by images and fictions of an imaginary museum. The LiMAC Project (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima), created in 2002, seeks to resemble what is internationally known as a contemporary art museum. LiMAC has no fixed physical location and operates through different formats. It has operated both in public spaces and virtual platforms, simulating in some cases a traveling sales stand with merchandising, in the style of a museum store, but with an itinerant character that questions the solemnity of conventional museum institutions. It is a critical manifestation that questions the authority and role of the museum as a cultural mediator. It not only re-signifies works of art, but also invites us to reflect on how museums influence the perception and valuation of art through this “museum void”10Sandra Gamarra, Agustín Pérez Rubio, Miguel A. López, Buen Gobierno, Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid; CA2M, 2021.. As critic Miguel A. López points out, LiMAC becomes a platform to destabilize official narratives and propose a space where the viewer reevaluates his or her relationship with images and their history11Idem. This project is fundamental to understand that museums are not only exhibition spaces, but also places where cultural meanings are negotiated, the temporality of images and their circulation in cybernetic and oral spaces.

Of museum necessity

“When men are dead, they enter history. When statues are dead, they enter art. This botany of death is what we call culture”12Chris Marker y Alain Resnais, Les statues meurent aussi (“Statues also die”), documentary, 1953.. So begins a controversial documentary by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais that questions the differences between African art and Western art, but above all the West’s relationship with that art. To wonder about museums is to wonder about the death of the object; to wonder about images in the museum context is to wonder about their reincarnation as meaning. For Flusser, in the philosophical tradition, reflection on the creation of images has most often been described speculatively under the name of imagination or imaginative faculty13Vilém Flusser, La imagen-cálculo: por una nueva facultad imaginativa, Madrid: Ediciones del Serbal, 2013, 41.. It is almost always understood there as something given, as a fact that is presumed to exist. Museums, therefore, function as a container of images, which, in their storage, keep signs, meanings, cultural changes and, of course, imaginary projects.

The contrast between Sandra Gamarra Heshiki and Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña -specifically between the LiMAC project and Cuerpos Blandos- responds to two links that can be identified when studying their works and their processes of work production. On the one hand, we have the museum as a container and as a canvas for both spaces: in the case of Gamarra Heshiki, the question is posed about a non-existent museum in the situated space. How to contain works, or images in this case, if there is no space to do so? Langlois does the inverse exercise, or rather, he is forced to do it: his work is uncontainable for the museum space of the MNBA. What happens to the work when it is not possible (or not wanted) to exhibit it? Gamarra intentionally asks for the museum; Langlois does it unconsciously or, perhaps, as a consequence of the rejection of his work and its inevitable burial (and subsequent reincarnation) in the MNBA’s cellar. The museum functions as an activating apparatus for both works, installing the problematic of their contexts in their own territories and the question about the meaning of the museum in the works and in their respective historical circumstances.

At this point, it seems impossible not to return to the studies of critical museology and ask about its influence on both works. As Brazilian theorist Frederico Morais points out, critical museology is a movement that seeks to redefine the role of museums in the region, making them more aware of and responsible for their cultural and social impact14Frederico Morais, Textos críticos 1968–1975, Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo, 2022, 32.. Within visual arts studies, it is possible to observe how, since the 1990s, there has been an iconic turn that, instead of focusing on a traditional art history -demarcated by styles, periods and signatures-, questions a history of images and their effects15W. J. T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. According to Nelly Richard, museums in Latin America have historically functioned as power devices that not only organize but also hierarchize cultural narratives16Nelly Richard, Residuos y metáforas: ensayos de crítica cultural sobre Chile de la transición, Santiago: Cuarto Propio, 1998, 28.

This deconstruction becomes essential to rethink how visual culture circulates and legitimizes itself in a postcolonial context and is strengthened with the arrival of the neoliberal system in the Southern Cone. The Cuerpos Blandos project is developed under the direction of Nemesio Antúnez, who was appointed director of the MNBA by the Popular Unity government. The cultural policies established during this government were aligned under critical museology and its main precursor in Chile, Mario Pedrosa. In the case of LiMAC, although there is no evidence that Gamarra was inspired by this current of thought (although it is evident in the museographic and museological tactics employed in his other works), it is important to note that in the Peruvian context there are a series of “fake museums” that were created during the 1990s and early 2000s, some of which were inspired by critical museology, what the Peruvian curator and researcher Gustavo Buntinx called “museotopias”17Gustavo Buntinx. Micromuseo (‘al fondo hay sitio’): Una travesía por la imagen. Lima: Micromuseo, 1997..

On the other hand, it is also interesting to raise the question of copying in both works. In Gamarra’s case, her line of work is based on the appropriation of images. In the rexhibition Buen Gobierno (2022) curated by Agustín Pérez Rubio, at Sala Alcalá 31 in Madrid, for example, she questions the established orders in the imaginary of Peru (through the Andean culture) and Spain (through the viceroyalty), delving into the colonial, extractivist and racist validity that still persists in the country, together with the neocolonial relationship that still prevails in Spain18Agustín Pérez Rubio, “Copiar la historia sin veladuras,” in Buen Gobierno, Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid; CA2M, 2021. Gamarra reproduces still lifes, family portraits, portraits of kneeling donors, landscapes, viceroyal religious painting or caste painting, but he gives them a little wink: she mixes them with Andean culture, he turns them into Nikkei. They are mestizo works, neither from there nor from here.

Gamarra is interested in the image, its forms of production and the contexts in which it is interpreted. Her work highlights how points of view vary according to the place and the conditions of translation, proposing a situated work that connects space with the processes of creation. At the same time, it invites us to critically question what we often overlook19Agustín Pérez Rubio, “Sandra Gamarra. Artista en foco,” Artishock Revista de Arte Contemporáneo, May 30, 2022: https://artishockrevista.com/2022/05/30/sandra-gamarra-heshiki-buen-gobierno/. LiMAC is not different from these other more recognized works; after all, it is a copy of an ideal museum. Gamarra occupies the mechanisms of the museum to appropriate the museum: she challenges the notion of authenticity and ownership of the art object. The idea of originality and authenticity is a fundamental pillar in traditional museology; however, in critical museology, this concept is questioned. LiMAC bases its collection on copies of works, subverting the idea that a work must be unique and “authentic” to have value. This principle also makes it possible to question the economic structures associated with art, in which authenticity is often linked to the economic value of a piece: it is, in itself, the value of the commodity20Pierre Bourdieu, La distinción: Criterio y bases sociales del gusto, Madrid: Taurus, 1979..

In the case of Langlois, the copy appears unintentionally. It is the museum itself that has copies, and Cuerpos Blandos unveils them as such. When the work is moved to the MNBA’s deposit, it is left behind in the same space occupied by replicas of classical sculptures made by art students, copies of cheap material acquired to become part of the museum’s collection. This essay will focus specifically on the photograph taken of Cuerpos Blandos in the warehouse, along with other predecessor material to the work, suggesting that these new elements (the reproductions of classical sculptures) become part of the work itself.

Amalia Cross, PhD in History, identifies two important possibilities in this juxtaposition-the work of Langlois and the sculpture replicas: on the one hand, “the double purpose and meaning contained in the plaster replicas is counterposed to the manufacture and value of Cuerpos Blandos, insofar as the plaster sculptures are distinguished as pieces of a past put in check”. On the other hand, “both sets of works share material precariousness and contribute to the questioning of the limits of representation and the body”21Amalia Cross Gantes, “Cuerpos blandos,” in Ensayos sobre artes visuales: Prácticas y discursos de los años 70 y 80 en Chile, vol. II, ed. Francisca Baeza, Javiera Parra, Amalia Cross y Felipe Godoy, Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 2012, 74.. From a metaphorical point of view towards institutionalism, the work in contrast to the sculptures could respond to the idea of leaving behind a museum that is “little updated with its context” to give way to the modernity Antúnez was looking for22Amalia Cross, El museo en tiempos de revolución: la transformación del MNBA durante la dirección de Nemesio Antúnez, 1969–1973. PhD dissertation, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, 2019, 82–124.

The Museum of copies (Gamarra Heshiki)

In Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote, Borges presents Pierre Menard, a writer who does not try to copy Cervantes’ Don Quixote, but rather to rewrite it word for word, which raises a profound reflection on originality, authorship and interpretation23Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote,” in Ficciones, Buenos Aires: Editorial Sur, 1944.. The central paradox of the story is that, although Menard’s words coincide with those of Cervantes, the context and the author’s position make them radically different. Replicating or copying is not simply an act of imitation, but a process that transforms the original into something new.

From another point of view, Walter Benjamin’s thesis on “aura” -expounded in his essay The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility- is essential to understand how copying affects the authenticity of a work of art24Walter Benjamin, “La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica,” in Discursos interrumpidos I, Madrid: Taurus, 1973. According to Benjamin, the mass reproduction of works, through photography and technology, destroys the unique “aura” that an original work possesses. Both Gamarra and Langlois (accidentally) explore the copy or replica and question this notion of aura. In LiMAC and in Cuerpos Blandos we can see the dichotomy of these two notions: on the one hand, the replication to build something completely different, and on the other hand, the loss of aura from the point of view of reproduction.

In Gamarra’s case, copying appears as an inherent technique in his work. Miguel A. López asks Gamarra in an interview published in the catalog of the Buen Gobierno exhibition at Sala Alcalá 31 in Madrid why there is a constant interest in copying and forgery. Gamarra answers that she belongs to a generation that lacks originals, where people in Peru studied from photographic copies in art schools. But, at the same time, copies continue to appear in “Chinese” toys, clothing and books:

“La universidad, por su parte, nos instruía para buscar la originalidad en nuestro trabajo, y año tras año me percataba de que nos repetíamos. Me preguntaba si, en todo caso, coincidir o ‘copiarnos’ no era lo más cercano al origen, entendiendo este como un lugar común, que se comparte. El interés por la copia o la falsificación vino por un descrédito de lo original como posibilidad. Hablando del ideal occidental de originalidad”25Sandra Gamarra, in Buen Gobierno, Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid; CA2M, 2021,176..

This problem is not only applicable to the world of art schools, but also to the Latin American cultural scene, where museums are based on a Eurocentric tradition that governs what belongs -and what does not- to what we call “culture”. This can be seen in the design of the MNBA, inspired by French architecture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially in the Beaux-Arts style that predominated in Paris during that period. This architectural style, which combined classical elements with ornamental details and modern techniques, was adopted in various buildings in Latin America as a symbol of modernity and progress. Sandra Gamarra acutely observes that these museum replicas come from a Western ideal of originality. So, it is worth asking ourselves: what is original for the Peruvian? What is original for the Chilean? Can we speak of an originality of the Southern Cone?

Gamarra does not have the answer to all these questions, but she does have a proposal that makes a historical review of Latin America. In her work, the artist does not point to viceroyalty painting as a copy, but as a representation strategy. The concepts of copy, false and mestizo are confused in her work. In this sense, we must not forget Gamarra’s biography: her paternal family is indigenous Peruvian, while her maternal family is Japanese, so there is a persistent interest in copying as a method to decipher one’s own identity.

The LiMAC collection consists mainly of copies of famous artworks that Gamarra paints based on images reproduced in art books. It also includes an online platform that hosts permanent exhibitions, a photographic record of temporary shows, and a fictional architectural project for a permanent headquarters imagined in the desert. This architectural proposal, according to curator Pamela Desjardins, 26Pamela Desjardins, “Desvíos y extrañamientos como crítica: las museotopías peruanas y la reimaginación del dispositivo museal,” Universidad Autónoma de México, 2020 1–13..“dismantles the marked significance that museum buildings have acquired (…) where the ‘wrapper’ becomes more important than the content,” parodying European and U.S. contemporary art museums in contrast to Latin American realities. It satirizes the standardized model of the contemporary museum dictated by the precepts of Global North metropolises, exposing the differences between Latin American conditions and traditional European or U.S. museum spaces. The project emerged during Gamarra’s first stay in Madrid, where, of course, there is an abundance of cultural institutions. The artist recalls with deep discomfort the way Europeans would ask about the Peruvian circuit: whenever she was asked about the scene in Lima, the listener perceived it as something “exotic.” These interactions helped her realize that museums are a framework outside of which their symbolic (and artistic) discourse remains incomplete.

“El LiMAC surgió como un lugar donde albergar esas primeras copias incipientes, para luego generar una colección de copias ya exentas de su fuente. El museo aparece como un reflejo: un espejo o espejismo de esos museos estándar o ‘museos aeropuertos’ que podías encontrar en cualquier parte del mundo, pero esta vez bamba”27Ibid, 178.

In LiMAC, authenticity emerges from copy and reproduction, questioning authorship and value in the museum. Her move from Lima to Madrid invites us to reflect on contemporaneity, places of enunciation and cultural hierarchies, challenging the canonical. As Gamarra herself says, “the narrative that includes us should be dictated by a need of our own and not by the desire of an other”28Idem.

As noted above in relation to the case of the MNBA, museums in Latin America were founded following European or U.S. models; however, these models often did not adapt to the budgetary and structural realities of Latin American cities. This structural mismatch resulted in unfinished institutions and, in many cases, in museums dependent on political will or the vagaries of public funding. Gustavo Buntinx coined the concept of the “museal void”29Gustavo Buntinx, MicroMuseo del Perú, video published by Museo Histórico Nacional, December 11, 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZEn2Crq76A to refer to the absence of a Museum of Contemporary Art in Lima. Yet, as Desjardins30Pamela Desjardins, “Desvíos y extrañamientos como crítica: las museotopías peruanas y la reimaginación del dispositivo museal,” Universidad Autónoma de México, 2020 1–13. argues, this very precariousness—far from being a mere sign of lack—created a fertile ground for rethinking the museum’s public function and its imaginative potential.

From this “void,” the so-called museotopías began to take shape: mobile and experimental initiatives driven by artists, curators, and collectives that challenge the spatial and conceptual stability of the traditional museum. These experiences propose alternative modes of museality, grounded in itinerancy, the temporary appropriation of spaces, and a critique of institutional hierarchies31Gustavo Buntinx, Lo impuro y lo contaminado: Pulsiones (neo)barrocas en las rutas de Micromuseo, Lima: Micromuseo, 2007, 68: https://micromuseo.org.pe/publicaciones/lo-impuro-y-lo-contaminado/.. Among these spaces are, in chronological order, Buntinx’s own Micromuseo; Fernando Bryce’s Museo Hawaii (1999); Susana Torres Márquez’s Museo NeoInka (1999); Sandra Gamarra’s LiMAC (2002); Giuseppe Campuzano’s Museo Travesti (2003); and César Cornejo’s Puno MoCa (2007). It is important to note that these “museotopías” are specific to Latin America; therefore, it is worth mentioning projects that are not only Peruvian but also from other countries: Museo la ENE in Argentina; Museo Internacional de Chile (Colectivo Mitch); GuggenSITO (Mexico); Museo Portátil (Brazil); Museo Bailable (Buenos Aires, Argentina); and M.A.M.I. (Museo Arqueológico del Machismo Inmemorial / Musea de Antigüedades Misóginas Increíbles / Musea Anti Machismo Interactivo / Musea de Arte Moderno e Insumiso / Musea Autónomo de Mujeres Intergalácticas), created by women from different parts of Latin America.

Gamarra knew Fernando Bryce’s Hawaii Museum and the Micromuseum, with which he was close to and collaborated with. Gamarra mentions that he saw in these projects what LiMAC was not, since they moved in a more “guerrilla” and “propositive” space (in his own words), while LiMAC was the parody of what we are not. Peruvian museotopias are the closest thing to what we really are: transvestite, small and mestizo spaces. Thinking about the museum from its place of enunciation puts on the table the possibility of asking ourselves about the desires of contemporaneity. When in 2015 the new Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima (which is private) is inaugurated, Gamarra is asked what will happen to the LiMAC project, to which he responds, “The appearance of one does not mean the death of the other. Isn’t an original more real when it meets its copy?”32Ibid., 178..

Museum copies (Langlois)

Ozymandias, a sonnet by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), relates the experience of a traveler who comes across the remains of a statue in the middle of a vast desert. The inscription on its pedestal proclaims the glory of Ozymandias, but the dilapidated state of the statue reflects the fragility of human conquests and the ephemerality of achievements33Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ozymandias,” in The Complete Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley, New York: Modern Library, 1994.. The figure of the traveler, as a witness to this scene, conveys a message about the transience of power. The king’s face lies destroyed in the earth, as a symbol of the disintegration of his legacy. The statue, broken in half, remains only as a vestige in the desert, a monument that, although it seems eternal, is destined to disappear with the passage of time. That fragility in tension over power, the ephemeral and the phantasmagoric, is Juan Pablo Langlois’ Cuerpos Blandos and the tension it generates in the museum space of the MNBA.

Cuerpos Blandos is a well-known work, but in some ways also underrated in the history of Chilean art. It is transcendental to understand the history of Chilean sculpture and the breakthrough of art, but for some theorists it is not a work that sets a precedent to be considered “contemporary”. Since this is the battleground, so dynamic and divided, it may be interesting to explore it from its installation canvas. In other words, in order to talk about Cuerpos Blandos, it is inevitable to talk about the MNBA.

The history of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes is winding and intricate. Amalia Cross, in her doctoral thesis, mentions that the construction of the Palace of Fine Arts responded to a need to improve the spaces for both the museum and the School of Fine Arts. In 1902, the Chilean government, through the Ministry of Public Works, organized a competition that was won by the architect Emilio Jécquier, who – as indicated above – was inspired by the museum standards of the French academy, reflecting the desire of the Chilean elite to emulate European canons34Amalia Cross, El museo en tiempos de revolución: la transformación del MNBA durante la dirección de Nemesio Antúnez, 1969–1973. PhD dissertation, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, 2019, 82–124..

The Palace of Fine Arts was conceived as a public space for the education and dissemination of art. Since its inauguration, the museum was intended to fulfill a civilizing function, contributing to educate the people through culture. Although for years it did not undergo major changes in its structure, the museum was consolidated as a cultural center of reference. In the 1960s, under the direction of Luis Vargas Rosas, it experienced an increase in its exhibitions, its visitors and the works in its collection. However, in 1969, with the arrival of Antúnez as curator, the conservative and elitist model that predominated in the museum was questioned. A renovation was then proposed to democratize access to art, transforming the museum into an active and participatory cultural center, in line with the ideas of “houses of culture” that promoted social participation and cultural accessibility. In the words of Antúnez, an “Open Museum”:

“Está claro, MUSEO ABIERTO significa que el museo se abre a los artistas de todas las tendencias artísticas, edades, formas de expresión, técnicas, y además se abre al gran público, que vendrá a VER el arte que se ha hecho y se hace hoy día en Santiago; en suma, un Museo que se abre a los artistas y a la ciudad después de muchos años cerrado o semicerrado por diferentes causas”35Nemesio Antúnez, “Presentación,” in Museo Abierto, Santiago: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1990, 3..

Inspired by critical museology (which was promoted by Salvador Allende’s government and by Mário Pedrosa36Mário Pedrosa (1900-1981) was a Brazilian art critic, political activist and journalist, recognized for his work in modern art criticism and his commitment to socialist politics. During his exile in Chile, after the military coup in Brazil, Pedrosa was invited by President Salvador Allende to lead the creation of the Solidarity Museum. In this context, he founded the International Committee of Artistic Solidarity with Chile, mobilizing artists of various nationalities to donate works to the museum. Pedrosa emphasized the importance of public accessibility to art, promoting educational and outreach programs that sought to bring modern and experimental art closer to the Chilean population, especially to popular sectors such as miners and peasants. His approach integrated art with the social-political process of the country, considering the museum as a space for cultural transformation and citizen participation. during his stay in New York), Antúnez decided to change the way the MNBA operated. He knew that the renovation of the museum required not only restorations and expansions, but a radical change in its structure and in the way it was conceived as a public space. Despite administrative difficulties and lack of budget, he set out to transform the museum into a place accessible to all, without losing sight of its educational purpose, as expressed in its artistic outreach programs37Amalia Cross, “El museo en tiempos de revolución”, in Antúnez Centenario, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2019: https://www.mnba.gob.cl/noticias/antunez-centenario.. He focused on revitalizing forgotten spaces, such as the Sala Forestal, which allowed for the continuous exhibition of works and became a reference for young artists. He also introduced changes in the museum’s collection, withdrawing European copies and incorporating works by contemporary national artists, popular, indigenous and Latin American art, and modern and contemporary manifestations.

The work that came to “inaugurate” these new proposals by Nemesio Antúnez was Cuerpos Blandos (Soft Bodies) by Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña. However, four days after its installation, due to the fact that the director of the MNBA, Luis Vargas Rosas, prioritized the inauguration of the exhibition Panorama de la Pintura Chilena, Cuerpos Blandos was moved to the museum’s warehouse, which marked a crucial moment in the history of this intervention. More than a simple logistical adjustment, this act evidenced the tension between the traditional values associated with the museum and the radical nature of Langlois’ proposal. The work, which had burst into the most visible spaces of the museum, was relegated to storage, a symbolic space of exclusion and marginality. In this regard, Langlois argued the following:

“Mi primera sensación fue un tremendo mal humor al no verla. Era cuando menos sorprendente que hubieran retirado una obra de esa envergadura, recién instalada, y sin una razón válida. Cuando me abrieron la sala donde había sido arrumbada, entreverada con toda clase de objetos de las bodegas del museo, sobre todo réplicas en yeso de esculturas clásicas, quedé sorprendido de la escena; saqué una fotografía de la sala abierta y le dije a Nemesio que reabriéramos la exhibición, tal como estaba, incluyendo la sala de la bodega. La foto que tomé de esa situación superó todo lo previsto. ¡Es la maravilla del azar, que suele acompañar favorablemente las obras! Había previsto que la obra podía cambiar durante su exhibición (en el catálogo escribí: ‘la obra material puede desaparecer después de expuesta o cambiar varias veces durante su exposición’) pero nunca imaginé que pudiese ser de ese modo. A mi juicio, esa sala replanteó lo que Nemesio buscaba para el nuevo Museo e hizo cobrar valor a lo que se decía escuetamente en el catálogo”38Juan Pablo Langlois, Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña: viaje sentimental 1969–1989, Santiago: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, 2008, 3.

In the cellar, Cuerpos Blandos was mixed with plaster replicas of classical sculptures, pieces that for decades had dominated the museum’s visual discourse and which corresponded to reproductions made by Art School students. This fortuitous encounter between the ephemeral and the monumental generated a new meaning for the work. Langlois not only re-signified his intervention, but also directly exposed the contradictions of the museum institution, which was still governed by the European canons of art despite its opening discourse39Amalia Cross, El museo en tiempos de revolución: la transformación del MNBA durante la dirección de Nemesio Antúnez, 1969–1973. Tesis de doctorado, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, 2019, 197-203. Gamarra’s words then resonate, “isn’t an original more real when it meets its copy?” Another parallelism then appears with the copies presented at LiMAC. The difference lies in the fact that, while in LiMAC they are used as a strategy implemented by Gamarra to represent the “essential” of a museum, in Cuerpos Blandos the copies are not intentional, but are added later as a central part of the work. After all, both the MNBA and the LiMAC are museums made of copies, and it is Cuerpos Blandos that brings out that aspect of the MNBA, which ends up being a reflection of those “Airport Museums”40Gamarra uses the term “airport museum” to refer to institutions that, despite their discourse of openness and modernization, maintain rigid and conservative structures that limit the active participation of the public and the inclusion of new narratives. This concept highlights the contradictions between the public image of museums and their internal practices, which often remain elitist and exclusionary. See Sandra Gamarra, Agustín Pérez Rubio, Miguel A. López, Buen Gobierno, Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid; CA2M, 2021, 45..

The displacement of Cuerpos Blandos to the MNBA’s warehouse deepened Langlois’ critique of the system of artistic validation. By being relegated to a space outside the exhibition circuit, the work highlighted the fragility of the structures that define what is and what is not art. Thus, instead of weakening the artist’s proposal, this displacement strengthened it by underlining how the museum continued to operate under parameters of exclusion. The work, now hidden among copies and remnants of another time, forcefully reflected the tension between emerging contemporary art and the institutions that received it with resistance.

In Difference and Repetition (1968), Gilles Deleuze argues that the copy represents a subordinate form of representation that follows the Platonic model, according to which its value is measured by its resemblance to an ideal original. This hierarchical logic privileges identity over difference, thereby limiting thought. In contrast, Deleuze proposes the concept of simulacrum, which does not depend on a model and operates from autonomy and difference, destabilizing the traditional structures of representation41Gilles Deleuze, Diferencia y repetición, Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2002, 89.. While the copy remains trapped in the regime of resemblance, the simulacrum celebrates multiplicity and becoming, freeing itself from representational thought and questioning the supremacy of the original. Is Soft Bodies not a simulacrum in a world of copies? The fortuitous destiny of this work, like LiMAC, reveals, in a certain way, the history of Latin America in the museum space: while Langlois sees an “accident”, Gamarra does it intentionally. Both works are straining the relationship between the copy and the museum.

The ghost is a shadow that insists, a presence that never dissolves

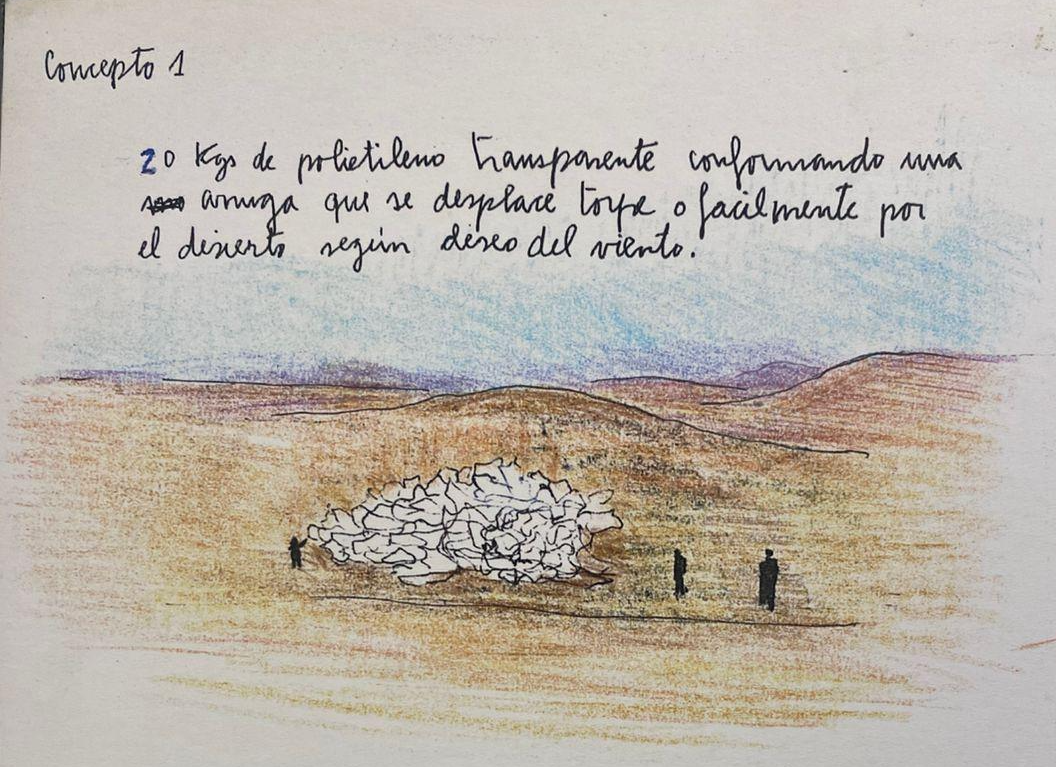

In addition to Cuerpos Blandos, another work of interest to analyze in this essay is a previous sketch by Langlois that was found in his archives and that belongs to projects from his final exam for his architecture degree. To a certain extent, these may be antecedents of Soft Bodies, since the use of polyethylene as the main material is repeated there. Below is the image of the project entitled “Concept 1”, belonging to a series of four projects, which take shape to be installed and developed in the Chilean desert. All these projects use fragile and precarious materials such as polyethylene, trash bags, newspapers, and various types of paper, which allows them to be transported with the landscape: the sand, the wind, the heat and the people activate these works and remind us of their permanent fragility. “Concept 1” is the one that most resembles the result of Soft Bodies; the difference is the size and that instead of being “a big worm” this is a mass that is deployed in the desert.

Juan Pablo Langlois, Proyectos de instalaciones no realizadas. Available in Il Posto Archive

It is striking that both Langlois and Gamarra see the desert as a place for the collection of works (it should not be forgotten that the fictional headquarters of Li-MAC is the desert). In Los hijos del limo (1974), Octavio Paz uses the desert metaphor to explore themes related to modern poetry, the break with tradition, and the search for meaning in a world that seems to have lost its spiritual and cultural foundations42Octavio Paz, Los hijos del limo, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1974.. The desert in this essay is not a physical place, but a symbolic concept that represents the emptiness, loneliness, and fragmentation of the modern individual in his or her relationship with language, history, and art. Paz argues that poetic modernity is born of a rupture with previous traditions, an act that, although liberating, leaves poets in a “desert.” This desert is a space in which inherited certainties and structures, be they religious, philosophical or mythical, have been abandoned. However, this loss is not only negative; the desert also presents itself as a space open to new possibilities, where authentic creation can emerge.

It seems poetic and metaphorical that both Langlois and Gamarra see in the desert an open space for the arrangement of works, considering also that both works question the canon and history. In the words of Octavio Paz, both Gamarra and Langlois are artists who are in a “desert”. The desert in Peru and Chile has a significant symbolic and material charge, especially in the context of extractivism, environmental damage and the dynamics of late capitalism. These arid regions have been transformed into scenarios of intensive exploitation of natural resources, with profound socio-environmental, cultural and political implications, being intervened by industries from first world countries. Copper, lithium and gold mines in these regions have not only plundered natural resources, but have turned the desert into a “landscape of sacrifice,” a space of environmental and social devastation at the service of global capitalism. This economic plundering also has a symbolic correlate, which can be related to the “museum void” revealed in both works: the desert, rich in histories and cultural meanings, is emptied of its own narratives in the works of art, becoming a silent and decontextualized stage for the accumulation of new uses, as also happens in Latin American museality from a critical museology perspective.

Langlois has always had a fascination with things that “move on their own”. In the archives of his unrealized works are the “Concepts” mentioned above, which are made of lightweight materials that allow the landscape to move, alter and move them. These are works that are incomplete without an “other” to activate them. Likewise, in the case of Cuerpos Blandos, according to Langlois himself, “the important thing was the act that, on its own, in time, was shaping bodies, without prejudice, without preform”43Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña, Cuerpos Blandos artist’s notebook with a record of the intervention at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile, 1968–1969. Available in Il Posto Archive.. That is to say: there was no interest in a specific body, but rather time was shaping the soft corporeality of the work. In itself, Cuerpos Blandos is an act of dislocation of the usual, so it creates awareness of that other body that inhabits the space. We are aware of an “other” that does not exist in a preliminary way; a body, we could say, that is a ghost in itself.

In the case of the LiMAC project the phantasmagoric is seen subtextually in desire; desire as a certain search, tendency or appetite for something, for example, a museum, which remains essentially unsatisfied44Jacques Lacan, Escritos 1, Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores, 2001, 47.. But also in something that is not or does not exist, the ruin of something, an inescapable pause45Walter Benjamin, Libro de los pasajes, Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2005, 102. In addition, Gamarra captures the phantasmagoria in two museum works: Miembro fantasma (Phantom Member) and in the Centro Infantil de Cultura Popular (Children’s Center of Popular Culture).

Carlos Garaicoa, De cómo la tierra se quiere parecer al cielo (I), 2005, installation with light, smoke, and 52 metal panels, LiMAC – Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima, Permanent Collection: https://li-mac.org/es/exhibitions/permanent-exhibition/phantom-limbs/open-voids/on-how-earth-wishes-to-resemble-the-sky-i/

The term “phantom limb” is used to describe the physical sensation that an amputated part of the body is still connected to it. Gamarra’s exhibition transposes this idea to the urban realm, focusing on architecture to explore its prosthetic character in relation to nature. Inspired by the peculiar condition of LiMAC, a museum in a city with an invisible and/or ghostly building, the exhibition brings together works that stand on the threshold between the visible and the invisible, the present and the absent, the prosthetic and the amputated, the ghostly and the living.

The exhibition is organized in three sections. The first, “Inhabited planes”, focuses on the internal structure of architecture, its skeleton. The second, “Isolated Areas,” highlights how architectural boundaries shape social dynamics and information flows. The third, “Open Voids,” explores the abandonment, decay, uprooting and transformation of buildings as part of a vital process. The selected works evoke the various “organs” that make a city function: scaffolding, prison doors, bus stops, museums, ruins, slums or neighborhoods. These prosthetic extensions, by generating tensions in these transitional spaces, reflect the strange, the alien and the spectral that inhabits cities.

On the other hand, the Centro Infantil de Cultura Popular embodies another facet of the phantasmagoria that permeates the LiMAC. This project proposes the rehabilitation of a former convent to transform it into a space for collective creation, a workshop where musicians, artists and actors converge. Its phantasmagoric nature resides in its liminality: it is a proposal that moves between what it was and what it could become. The convent, as a ruin, is a mute witness of a tangible past, while the projected workshop symbolizes a future full of potential, although always uncertain.

Walter Benjamin gives the perceptive and vital experiences of individuals, immersed in a daily life marked by constant interaction with material products and creations, the character of phantasmagoria46Ibid., 211–215.. These experiences, although always possessing a sensitive dimension, are simultaneously conditioned and guided by ideas that, in turn, feed on them. In this way, ideas, cultural manifestations in their corporeal-material form and the intricate realm of experience are interwoven in the concept of “phantasmagoria”, establishing a relationship of mutual influence and determination. The phantasmagoria of the Children’s Center becomes evident, as the space is caught between deterioration and the promise of revitalization, between the absent and the possible. Thus, the work seeks not only to be a physical meeting place, but also an idea under construction that evidences the desire for an inclusive space for creation and cultural exchange. In this sense, it aligns itself with the tensions that run through the other works of LiMAC, underlining its spectral condition. It is not surprising that the work Gamarra paints for the center is a boy dressed as a ghost hidden among the furniture of a convent: a metaphysical entity that represents the illusory, imaginary and false nature of the project.

Sandra Gamarra, CICIP – Centro Infantil de Cultura Popular (2012), painting, exhibited in Exposiciones temporales LiMAC, Guimarães Capital Europea de la Cultura, Proyecto Laboratorio de Curadores: https://li-mac.org/es/tag/painting/page/13/

Closure

“A bag full of papers in a museum is a concept. And from there, it acquires true meaning”47Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña, cited in the catalogue of the exhibition Viaje Sentimental 1969–1989. Juan Pablo Langlois Vicuña, Santiago: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, 2008, says Langlois Vicuña about Cuerpos Blandos. The museum as a container of copies, as a retainer of capital, and as a validator of images cannot be thought of without the multiple layers of power that sustain it and, in turn, feed the global cultural industry. Langlois, with precarious materials and an ephemeral work, confronts these structures by denying his piece the possibility of becoming merchandise. His vulnerable and transitory polyethylene and newspaper bag points out that the value of art does not lie in its material permanence or its circulation in the market, but in its ability to activate critical senses and challenge the institutional logics that seek to contain it. In this gesture, there is a desire for dematerialization that not only challenges the traditional notion of a work of art, but also proposes a space of resistance against the fetishization of the artistic object.

Decades later, Sandra Gamarra revisits these tensions from another angle: at LiMAC, she constructs an imaginary museum that replicates and recontextualizes established works from the global canon. Here, the copy is no longer a threat to value, but rather a tool for destabilizing it. If, as Marx argues, value is crystallized in the socially necessary labor required to produce a commodity, Gamarra questions this premise by replicating works already legitimized by the market and art history. Does artistic value lie in the authenticity of the object, in the labor invested in it, or in the commercial circulation networks that sustain it? LiMAC proposes a critical museum that appropriates universalizing museological strategies to discuss the museum from a perspective situated in the Southern Cone. In this gesture, the copy becomes a device that exposes the cultural and economic hierarchies that define which objects are worthy of preservation and exhibition, and which remain outside hegemonic narratives.

Both Gamarra and Langlois reveal the contradictions of an artistic system that oscillates between the production of meaning and the production of value. Their works, although very different in form and context, converge on a question that remains open: is it possible to think of art outside its condition as a commodity? Can a museum exist without replicating the logic of accumulation and exclusion inherent in cultural capitalism? These questions are especially urgent in Latin America, where the history of museums is marked by colonial relations, symbolic disputes, and tensions between the local and the global.

Rather than offering certainties, these practices open up a field of reflection on authenticity, copying, value, and the place museums occupy in the production of knowledge and cultural memory. Just as Gamarra and Langlois raised these questions in their works, we can assume that other artists from the Southern Cone will continue to explore these tensions. Perhaps, as Gamarra suggests, “an original is no more real when it encounters its copy.”

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W. Prismas: Crítica cultural y sociedad. Traducido por Jesús Aguirre. Madrid: Taurus, 1962.

Antúnez, Nemesio. “Presentación,” en Museo Abierto, Santiago: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1990, 3.

Bagnara Letelier, Javiera, Boletín Nº9 Juan Pablo Langlois, Santiago de Chile: Fundación CEdA, 2021.

Benjamin, Walter. “La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica,” en Discursos interrumpidos I, Madrid: Taurus, 1973.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, 1972.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote,” en Ficciones, Buenos Aires: Editorial Sur, 1944.

Bourdieu, Pierre. La distinción: Criterio y bases sociales del gusto. Madrid: Taurus, 2002.

Buntinx, Gustavo. MicroMuseo del Perú. Video de 1:32:21. Publicado por Museo Histórico Nacional. 11 de diciembre de 2015. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZEn2Crq76A.

Buntinx, Gustavo. Lo impuro y lo contaminado: Pulsiones (neo)barrocas en las rutas de Micromuseo. Lima: Micromuseo, 2007. https://micromuseo.org.pe/publicaciones/lo-impuro-y-lo-contaminado/.

Crimp, Douglas. On the Museum’s Ruins. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Cross, Amalia. “Cuerpos blandos.” En Ensayos sobre artes visuales: Prácticas y discursos de los años 70 y 80 en Chile. Vol. II, editado por Francisca Baeza, Javiera Parra, Amalia Cross y Felipe Godoy, 65–98. Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 2012.

Cross, Amalia. El museo en tiempos de revolución: la transformación del MNBA durante la dirección de Nemesio Antúnez, 1969–1973. Tesis doctoral, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, 2019: https://repositorio.uc.cl/handle/11534/74845.

Cross, Amalia. “El museo en tiempos de revolución,” En Antúnez Centenario, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2019: https://www.mnba.gob.cl/noticias/antunez-centenario.

Deleuze, Gilles. Diferencia y repetición. Traducido por María Silvia Delpy y Hugo Beccacece. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2002.

Desjardins, Pamela. “Desvíos y extrañamientos como crítica: las museotopías peruanas y la reimaginación del dispositivo museal.” Universidad Autónoma de México (2020): 1–13.

Escobar, Ticio. El arte fuera de sí. Asunción: Centro de Artes Visuales / Museo del Barro, 2004.

Flusser, Vilém. La imagen cálculo: Por una nueva facultad imaginativa. Barcelona: Herder, 2000.

Gamarra, Sandra, Pérez Rubio, Agustín y López, Miguel A.. Buen Gobierno. Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid / CA2M, 2021.

Lacan, Jacques. Escritos 1, Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores, 2001.

Langlois Vicuña, Juan Pablo. Viaje Sentimental 1969–1989. Catálogo de exposición. Santiago: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, 2008.

Marker, Chris y Resnais, Alain, Les statues meurent aussi (“Las estatuas también mueren”), documental, 1953.

Marx, Karl. El capital. Crítica de la economía política, vol. I. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2003.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Morais, Frederico. Textos críticos 1968–1975. Editado y traducido por el Grupo de domingos: Ignacia Biskupovic, Renata Cervetto, Jessica Gogan, Mônica Hoff, Lola Malavasi, Nicolás Pradilla y Mariela Richmond. s.l.: Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo, 2022.

Paz, Octavio. Los hijos del limo. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1974.

Pérez Rubio, Agustín. “Sandra Gamarra. Artista en foco.” Artishock Revista de Arte Contemporáneo, 30 de mayo de 2022. https://artishockrevista.com/2022/05/30/sandra-gamarra-heshiki-buen-gobierno/.

Pinochet Cobos, Carla. Derivas críticas del museo en América Latina. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI Editores, 2014.

Preciado, Paul. El museo apagado. Pornografía, arquitectura, neoliberalismo y museos, Buenos Aires: Fundación MALBA, 2017.

Richard, Nelly. Residuos y metáforas. Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre Chile de la transición. Santiago: Cuarto Propio, 1998.

Risco, María. “De limpieza y olvido: Apuntes de un diálogo con Juan Pablo Langlois.” En Ensayos sobre Artes Visuales: Prácticas y discursos de los años 70 y 80 en Chile, Vol. II, editado por Francisca Baeza et al. Santiago: Lom Ediciones, 2012, 253–260.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Ozymandias.” En The Complete Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley, New York: Modern Library, 1994.

Sloterdijk, Peter. Esferas I. Traducido por Isidora Guerrera. Madrid: Siruela, 2014. Ebook.

Valéry, Paul. “El problema de los museos.” En Piezas sobre arte, traducido por José Luis Arántegui, 105-107. Madrid: Visor, 2005.