Introduction

I am a slow painter

To think about an era is to look at what builds up around its edges: the debt owed to unresolved desires, the fatal insistence of everyday life, the impermanence of the forms and objects that make up its imaginary world. How does a particular moment take place on bodies? How does one time rest on another? An era—or more specifically, a decade—is also revealed in the reflection of lights on a street at dusk, in a face disfigured by the daze of memory, or in the desire to confirm the existence of things even when we know they are destined to disappear.

Ricardo Yrarrázaval. Three decades brings together for the first time at Il Posto the pictorial practice of Chilean artist Ricardo Yrarrázaval carried out between the early 1960s and the late 1980s. Based on works from different collections, the exhibition traces a journey through nearly thirty years of production. Returning to Yrarrázaval’s work today means confronting figures and imaginaries that resist fixation. They express an archaic artificiality, where representation insists on approaching a simulated other: anonymous and displaced figures whose identities are lost on the canvas. These images allow us to trace an archaeology of masculinities: rigid and mysterious presences, subjected to the rules of the city and labor, which expose the fragility of their cosmetics as well as the power of their gazes. This body of work, this social novel and set of accumulated gestures, is sustained by disidentification and thus opens up a space for thinking difference. The pastiness of time in Yrarrázaval, its accumulation and delay—characteristic of both an era and a gaze—are also the rhythm with which the artist practiced painting: with waiting.

The first decade

How to survive the dullness

The 1960s have their origins in a journey. The third of a series of decisive trips in Yrarrázaval’s formative years, during which the artist was able to continue his artistic education outside the schools and academies of Santiago. At the age of twenty—after a forty-five-day voyage on a saltpeter freighter—he settled first in Rome and then in Paris, cities where he trained and met Isabel, who would later become his wife. After returning to Santiago for a few years, he traveled again to France to further his studies in ceramics and later continued his studies in painting in London, in the home-studio of a painter who, during those same years, painted nocturnal atmospheres charged with mystery, rendered in rough and sad strokes.

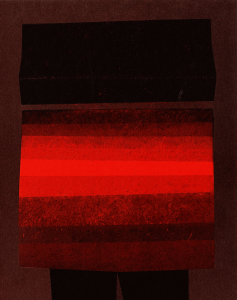

The years that were to come—the turbulent and emerging decade of the 1960s—would be marked by a third inaugural trip and would witness the development of a style of painting based on the experience of an artist trained in ceramics. In 1960, alone and aboard an old jeep, Yrarrázaval embarked on a four-month journey through the Andean countries, approaching for the first time the vast and silent landscapes of the altiplano. He began in Mendoza, crossed the pampas and the desert of northern Argentina, and continued through Bolivia and Peru until he reached northern Chile. There, for the first time in person, he encountered the motifs that would set the tone, texture, and structure of his painting for the next ten years. Upon returning from this journey, he remained silent: three years passed before he picked up his brush again with determination. His first material and earthy paintings emerged, dark at first, but over time they began to open up to the dominant color of his later work. The titles of these works—a kind of literature in the form of footnotes—reveal the impact that the territory he visited had on him. Attachement à la Terre (1964), the earliest work in this exhibition, presents a composition that moves naturally from the zenith to the front, where forms are not as important as the appearance of faint colors and the subtle differentiation between them.

Fig. 1. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Attachement à la Terre, 1964

In a conversation with his brother Renato many years later, Yrarrázaval recalls these early works, which he himself “never considered abstract”1Ricardo Yrarrázaval, conversation with Renato Yrarrázaval published in Cinco expresiones de la figuración en Chile. Dávila, Lira, Yrarrázaval, Bru, Smythe, Galería Cromo, Santiago, 1977 (n/p).. Rather than an exercise in pictorial representation, their results were determined by the gesture of sculpting, inherited from his training as a ceramist. The “sensuality of these paintings” comes precisely from this inflection of bodily molding on the pictorial surface. In their book Chile Arte Actual, Galaz and Ivelic stress this: “These technical procedures,” the authors argue, “allow [Yrarrázaval] to achieve intense corporeal forms that go beyond the purely visual level observed as surface, suggesting volumetric images that invite touch”2Gaspar Galaz and Milan Ivelic, Chile. Arte Actual, Ediciones Universitaria de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, 1988, p. 286. It is not surprising, then, that these paintings did not find a place within the repertoire of work of the geometric avant-garde groups, which were at their peak in the 1960s. Rather than pursuing a “defined geometry,” Yrarrázaval’s quest was for a language capable of inhabiting the edges.

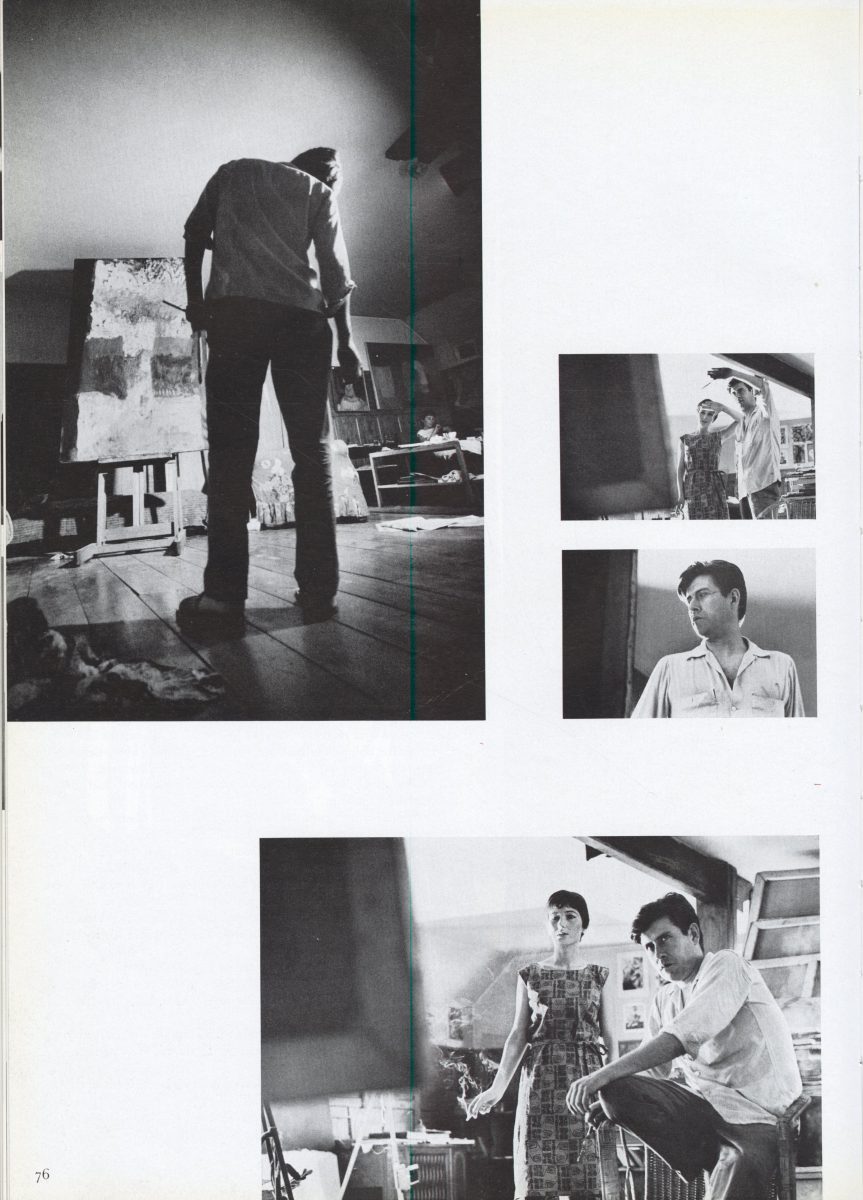

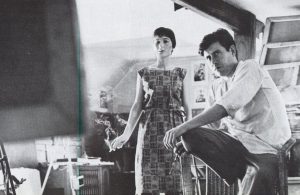

The second half of the 1960s was marked by the visit to Santiago in September 1964 of Thomas Messer, then director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Recommended by writer Jorge Elliot, Messer visited Yrarrázaval at his home-studio, an encounter that led to the artist being invited to participate in the exhibition The Emergent Decade. Latin American Painters and Paintings in the 1960s (Guggenheim Museum, 1966), where he would be the only Chilean artist with a separate section in the catalog3See Thomas Messer, The Emergent Decades. Latin American Painters and Painting in the 1960’s, Londres, Thames & Hudson, 1966, pp. 74-80. In those pages, portrayed alongside other Latin American artists by the photographer accompanying Messer, Yrarrázaval appears in his studio and at home. The black-and-white images show a patient and observant painter, but also one who is accompanied: Isabel, his wife, poses beside him with a lit cigarette between her fingers, or sitting on a sofa in the corner of the studio where he works. Her smile and the presence of their children convey a particular sense of affection.

.

Figs. 2 and 3. Photographs published in the catalog of the exhibition The Emergent Decade. Latin American Painters and Paintings in the 1960’s (Guggenheim Museum, 1966). Available in Il Posto Library.

The same year as the exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, Yrarrázaval received the Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to move to New York for a full year. The city and the fascination he felt for this experience shifted the material and spiritual density of his early works toward the events of the lives that began to populate his pictorial repertoire. From Presencia Ancestral (“Ancestral Presence”) (1965) he moved on to Minero (“Miner”) (1966) and other archetypal figures of popular culture that tentatively began to claim their place in painting. The appearance of these characters reflects an exercise of overcoming: one that seeks to transform the initial experience of the decade—the “gray of the altiplano” and Andean objects—into a painting capable of “surviving the dullness”4Pedro Celedón, “La estética del silencio”, en Retrospectiva 50 años. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Sala de Arte Fundación Telefónica, Santiago, 2002, p. 12.

Fig. 4. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Presencia Ancestral, 1965

Fig. 5. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Minero, 1966

The second decade

The gesture exists in time

For Yrarrázaval, the 1970s were a period of artistic transformation—both personal and collective—and of inscription in the national circuit of criticism and exhibition. In 1973, a month before the tragic event that would mark the years to come, the artist exhibited alongside Juan Pablo Langlois, Roser Bru, and Nemesio Antúnez in the exhibition La imaginación es la loca del hogar (“Imagination is the Madwoman of the House”), held at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Santiago. There, he presented for the first time, institutionally and in Chile, a broader collection of his pictorial production. Among the works exhibited were Su Ego (1973) and La Toilette (1973), both on display today at Il Posto. The indeterminacy of genres and contexts in which these paintings are situated opens a door to the silence and inner turmoil of a moment.

Fig. 6. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Su Ego, 1973

Fig. 7. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, La Toilette, 1973

After the military coup, Yrarrázaval temporarily lost two of his closest friends and supporters: gallery owner Carmen Waugh and Antúnez himself, with whom he maintained an active correspondence in which he would later describe the suffocating atmosphere of Chilean society at the time. This scenario leads his characters to live in a “state of expectation, scrutinizing the distance sometimes interrupted by nightfall, the escape of the horizon, or the condensation of the atmosphere”5Nelly Richard, untitled text published in Exposición de pasteles de Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Galería Época, Santiago, 1976 (n/p). In 1977, he participated alongside Juan Dávila, Benjamín Lira, Roser Bru, and Francisco Smythe in the exhibition Cinco expresiones de la figuración en Chile (“Five Expressions of Figuration in Chile”) at Galería Cromo, directed by critic and curator Nelly Richard. The catalog for this exhibition presents the intimacy of a Yrarrázaval who is still searching for his place: in his words, the construction of “a realism that would disturb” was determined by his circulation through the city6Ricardo Yrarrázaval, conversation with Renato Yrarrázaval published in Cinco expresiones de la figuración en Chile. Dávila, Lira, Yrarrázaval, Bru, Smythe, Galería Cromo, Santiago, 1977 (n/p). There, he mentions for the first time how much of his work comes from observing certain cold characters on the streets in whom he never ceases to perceive something mysterious. The uniqueness of this urban experience and the emotional weight with which it transforms his painting allows him to stand out in the middle of a scene undergoing profound change.

Fig. 8. Catalog of the exhibition Cinco expresiones de la figuración en Chile. Dávila, Lira, Yrarrázaval, Bru, Smythe (Galería Cromo, 1977). Available in Il Posto Archive

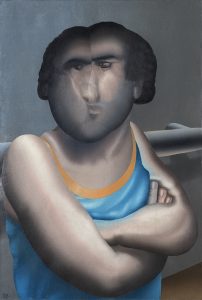

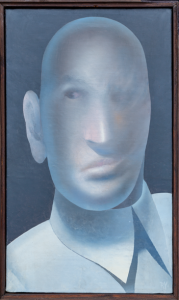

In the midst of a city ravaged by death, these paintings appear like lost skins, emptied of substance and yet expectant of their future. In the silent search undertaken by Yrarrázaval in the 1970s, gestures emerge as a tiny measure to record the pain, suffering, and shock of others and their impact on the artist himself. Each stroke contains the fragility of a displaced body and, at the same time, the obstinacy of a presence that refuses to disappear. Works such as En el gimnasio (“In the Gym”) (1979) and Retrato (“Portrait”) (1979) encapsulate this tension: the gazes that appear there seem to close one era and, at the same time, inaugurate another. They show that “the gesture exists in time”7Idem, always incomplete, always yet to come.

Fig. 9. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, En el gimnasio, 1979

Fig. 10. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Retrato, 1979

The third decade

I can’t stop thinking about their lives

On November 13, 1983, Ricardo Yrarrázaval wrote to his friend Nemesio Antúnez from afar. In the letter, he told him about his recent exhibition at Galería Plástica Tres, entitled Pintura (“Painting”). With deep sadness over the effect that the social context was having on his work, he mentioned the predominant gray color of the pieces. The subjects, he said, were “the men who try to create an artificial, distorted, false world. The men who, regardless of the means, seek power. Power that means bombs, war, pollution, hunger, hatred, the destruction of nature, the destruction of reality.” And then the artist says, “My intention was to paint the reality we live in. I didn’t succeed… Reality is so powerful! I will keep trying, I feel an urgent need to achieve even a glimpse of the terrible reality””8Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Letter to Nemesio Antúnez, november 13, 1983.

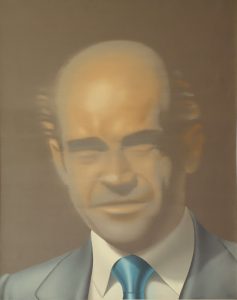

These words already hint at artificiality as a persistent question: humanity covered in fiction, the social mask of suits and offices. Yrarrázaval had been familiar with this aesthetic since childhood, through the figure of his father, a stockbroker. Decades later, these codes of rigidity and anonymity resurface in his paintings as traces of a learned masculinity put into crisis.

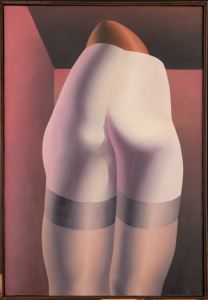

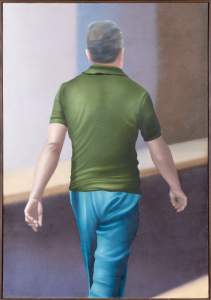

The paintings that Yrarrázaval produced during this period—the 1980s—are displayed at Il Posto as a palimpsest of correspondences and gazes: faces with varying degrees of literalness, erasure, and material density. In his essay “Estética del silencio”, Pedro Celedón focuses on Estrategias y pronósticos (“Strategies and Forecasts”) (1983), one of the works included in this exhibition, to point out that “the pictorial response generates half-erased faces, as if a mist were superimposed on their humanity,” and that “the contrast between the humanity of that blurred face and its metallic tie, absolutely defined, immaculate, becomes painful”9Pedro Celedón, “La estética del silencio”, in Retrospectiva 50 años. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Sala de Arte Fundación Telefónica, Santiago, 2002, p. 16. At the end of the room, a single painting closes the exhibition: Sin Vuelta Atrás (“There is no coming back”) (1980). The back of a man walking away from us sums up, in a minimal gesture, the weight of an entire era. The decade closes with its own beginning: the impossibility of returning. Yrarrázaval says it in words that resonate with his images: “When I go downtown, I am very aware of the atmosphere in that bank, in that public office. I am intrigued by those men, cold, anonymous characters. I can’t stop thinking about their lives, their desires, their ambitions”10Ricardo Yrarrázaval, conversation with Renato Yrarrázaval published in Cinco expresiones de la figuración en Chile. Dávila, Lira, Yrarrázaval, Bru, Smythe, Galería Cromo, Santiago, 1977 (n/p).

Fig. 11. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Estrategias y pronósticos, 1983

Fig. 12. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Sin vuelta atrás, 1980

References

Pedro Celedón, “La estética del silencio”, in Retrospectiva 50 años. Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Sala de Arte Fundación Telefónica, Santiago, 2002, pp. 6-18 6-18.

Gaspar Galaz and Milan Ivelic, Arte Actual, Ediciones Universitaria de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, 1988.

Thomas Messer, The Emergent Decades. Latin American Painters and Painting in the 1960’s, London, Thames & Hudson, 1966.

Nelly Richard, untitled text published in Exposición de pasteles de Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Galería Época, Santiago, 1976 (n/p). Available in Archivo Nemesio Antúnez: https://fundacionnemesioantunez.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/E1843.pdf

Ricardo Yrarrázaval, conversation with Renato Yrarrázaval published in Cinco expresiones de la figuración en Chile. Dávila, Lira, Yrarrázaval, Bru, Smythe, Galería Cromo, Santiago, 1977 (n/p).

Ricardo Yrarrázaval, Letter to Nemesio Antúnez, November 13, 1983. Available in Archivo Nemesio Antúnez: https://fundacionnemesioantunez.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/E1696.pdf