The rigid borders of territories create two separate realities: an inner and an outer one, an us and a them. In this sense, a territory constitutes a “semiotic structure” that produces and delimits identities. Our subjectivities are then the result of the creation of the territory, the same one that, from a conceptual perspective, imposes through its rigid borders an artificial order in those places where there is indeterminacy and confusion. Likewise, the notion of identity attempts to impose artificial categorizations on the fluidity of existence, that is, on the “anarchic heterogeneity of reality”1Simone Aurora, “Territory and Subjectivity: the Philosophical Nomadism of Deleuze and Canetti”, in Minerva N° 18, 2014, p. 11. What would it mean to embrace this anarchic reality and move towards a form of subjectivity that transcends rigid borders? What would a borderless territory, a no man’s land, look like? And how would this complexity manifest itself aesthetically?

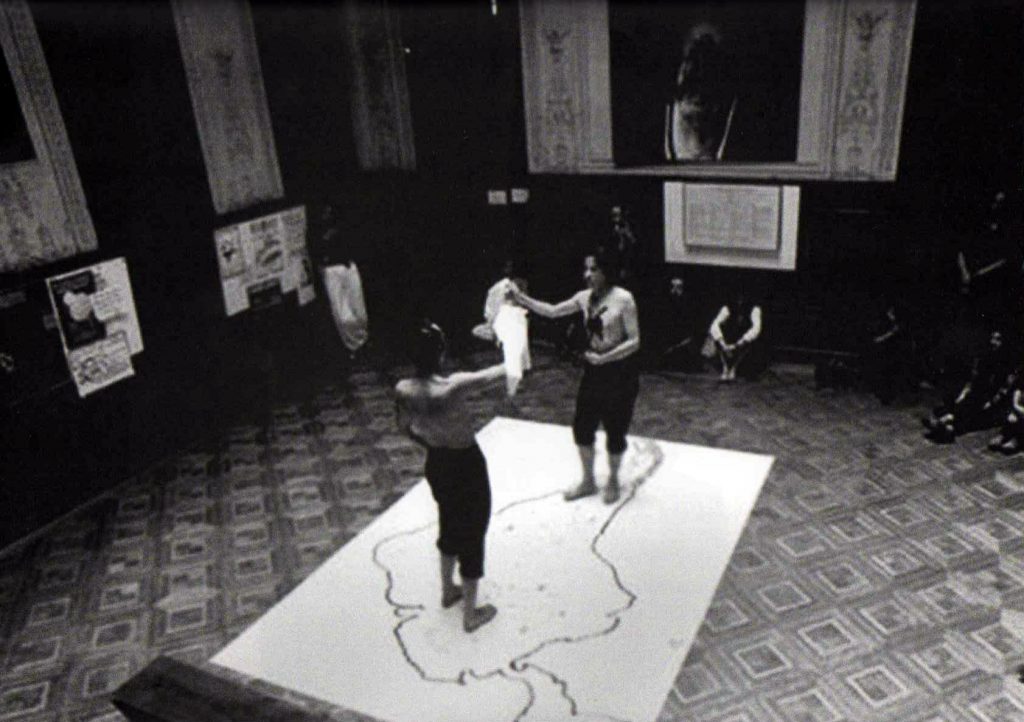

On October 12, 1989, as part of the commemoration of what today is called the “Day of the Encounter of Two Worlds” in Latin America, las Yeguas del Apocalipsis, a performance duo formed by Pedro Lemebel and Francisco Casas, presented a work at the headquarters of the Chilean Human Rights Commission entitled La Conquista de América. With walkmans attached to their chests, the artists danced barefoot on shards of glass to the sound of a cueca song that only they could hear. The glass, which came from Coca Cola bottles, covered a map of South America without borders, a no man’s land. In this way, las Yeguas established a direct link between the conquest of America and the colonial logic of U.S. interventions in the violent political history of 20th century Latin America. At the same time, the artists recreated on the bloody map the “cueca sola”, a symbolic act of appropriation performed by Chilean women whose husbands, fathers and relatives had been victims of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. Thus, las Yeguas also danced the women’s part as a symbolic alignment with the feminine and as an act of gender dissidence. As in many of their other works, Casas and Lemebel explored in this performance different territories: indigenism, latinidad, national identity, gender and sexuality.

Fig. 1. Yeguas del Apocalipsis, La Conquista de América, 1989

Throughout their practice, las Yeguas del Apocalipsis appropriated cultural symbols, infiltrated places of power and represented with their dissident bodies what they called “a warrior queerness”2Cecilia Lanza, Crónicas de la identidad: Jaime Sáenz, Carlos Monsiváis y Pedro Lemebel, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, 2004, p. 107, playing with the rigid notions of social identification that prevailed until the last days of the Pinochet dictatorship. They played, for example, the role of the “sudaca, the maricón, the poor, the aindiado”3Walescka Pino-Ojeda, “Gay Proletarian Memory: the Chronicles of Pedro Lemebel”, in Continuum, Vol. 20, N° 3, 2006, p. 396, but never prioritized or maintained one of these identities for long, always refusing to remain the same. Throughout their written and visual work, las Yeguas created territories, but only to leave them behind and established others, constantly changing shape and manifesting themselves in different points across the margins. In this sense, their work exists -to continue their guerrilla logic- in no man’s land: a middle ground, liminal insofar as it does not belong to any particular subject. That is to say, a point where nothing is fixed and where one is in a constant process of becoming, not of being.

This exhibition brings together twelve Latin American artists who examine identity through notions such as class, gender, ethnicity and race. Twelve artists who examine how identities are constructed and, in many cases, how they have been imposed on them, and who express through their practice their individual subjectivities without succumbing to universality or essentialism. The exhibition presents, mainly, works from two periods in which identity politics was the protagonist in artistic and curatorial discourses: the 1980s and the contemporary era. Using the works of las Yeguas del Apocalipsis as a guide, the exhibition is organized into three categories that highlight the conceptual and aesthetic (dis)continuities between works that explore the representations of different identities: Appropriations, Circulations and Body-Territories.

Appropriations

During the years of the Pinochet dictatorship, a group of Chilean women appropriated a nationalist symbol, the cueca, to turn it into the “cueca sola”. The national dance, which was traditionally performed by a man and a woman, was performed in this case by a woman alone, highlighting the absence of the men who disappeared in the context of the dictatorial regime. While the “cueca sola” was already transgressive in the way it included the disappeared, the cueca performed by Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis, an appropriation of this appropriation, incorporated the queer subject.

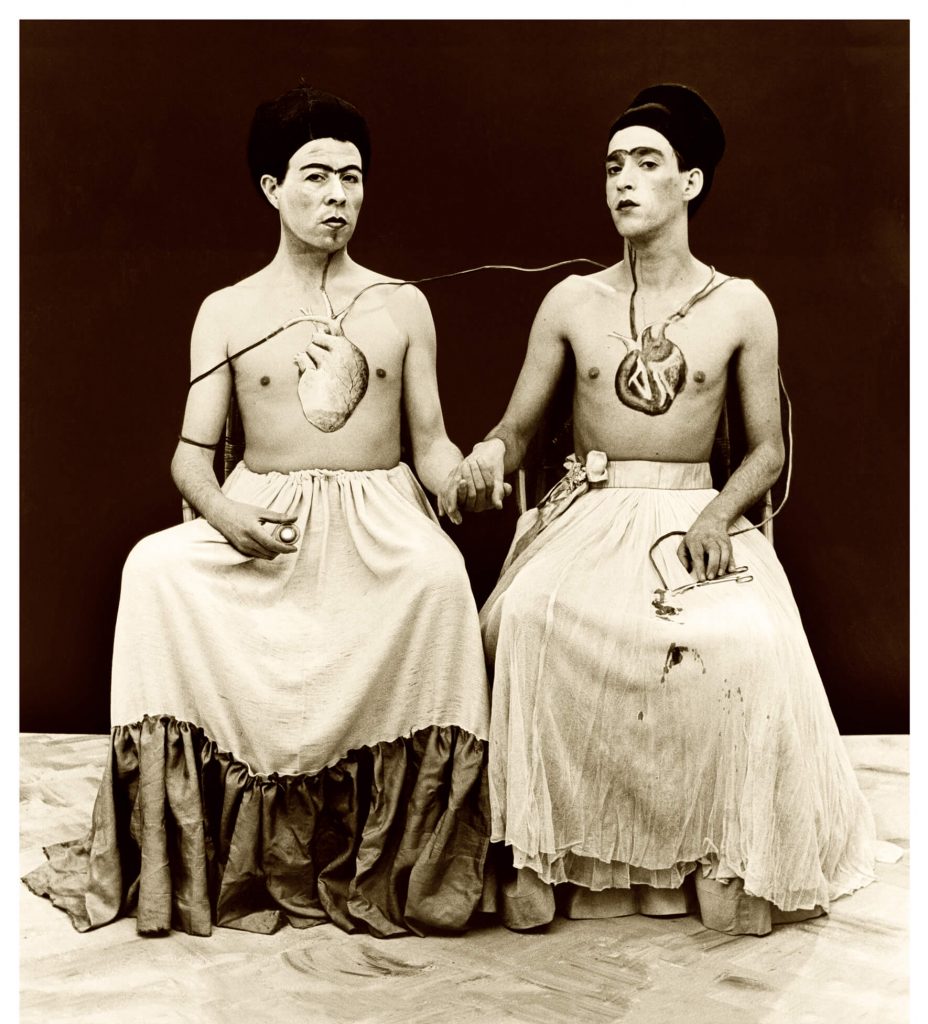

Likewise, in Las Dos Fridas (1989), las Yeguas appropriated another symbol of popular culture, Frida Kahlo’s famous 1939 painting, recreating it as a tableau vivant. By placing their bodies in the composition, connected by a blood transfusion tube, the duo recontextualized the work to reference the HIV pandemic. Casas calls this act of transformation a “becoming-Frida Kahlo”4Audio record of Francisco Casas available on MoMA’s website. Accessed 07/08/2024: https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/298/4365 , referencing Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s notion of becoming, which argues that identities are not static in our fluid reality and that we are in a constant process of transformation and change, in a continuous process of becoming. Meanwhile, Lemebel describes the appropriationist strategy of Las Yeguas as a chameleonic exercise, a process of constant transformation that is enunciated from:

…those broken, defected places, which are constantly rebuilding themselves to survive in an overwhelming system (…) I borrow a voice, I make a ventriloquism with those characters. But I am also me; I am poor, homosexual, I have a female becoming and I let it pass5Pedro Lemebel cited in Juliana Sandoval Alvarez, “Sospechas maricas de la cueca democrática: arte, memoria y futuro en “Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis”(1988-1993)”, in Estudios de Filosofía N° 58, 2018, p. 22.

Fig. 2. Yeguas del Apocalipsis, Las dos Fridas, 1989

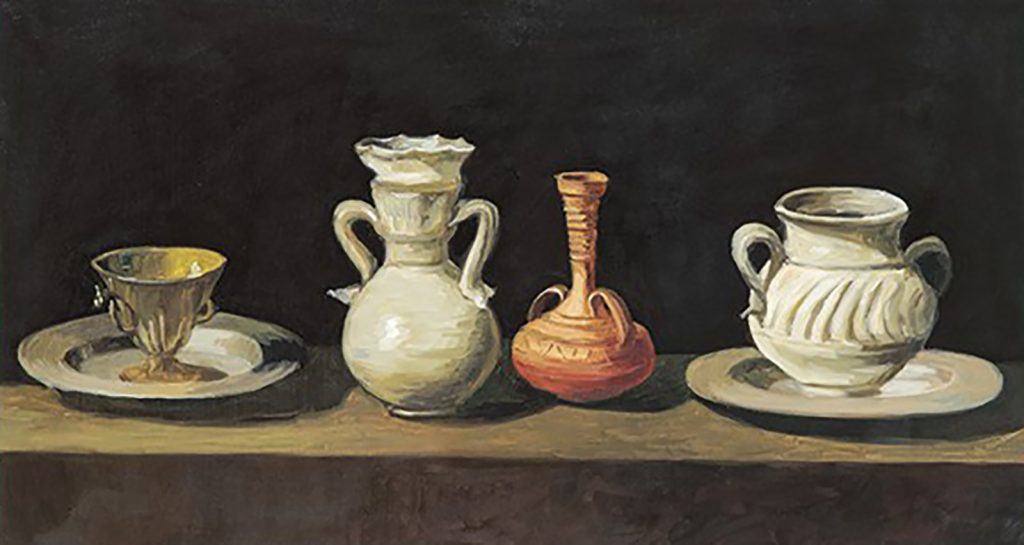

The artists exhibited in this first section also experience this chameleonic exercise, transforming themselves and taking reference points that do not belong to them in a subversive act to transmit their individual subjectivities. On the one hand, Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra, just like Lemebel and Casas, borrows voices, recreating the art of pre-Columbian, colonial and western cultures to recontextualize it and unveil its hidden histories. This is the case of Otras Fuentes II (2009) and Otras Fuentes III (2009), where the artist appropriates canonical genres of European art history -the traditional portrait and the still life-, imitating works from the colonial period to blur the boundaries between production and reproduction, the original and the imitative or the authentic and the spurious.

Fig. 3. Sandra Gamarra, Otras Fuentes II, 2009

Fig. 4. Sandra Gamarra, Otras Fuentes III. Opus 0136, 2009

Antonio Pichillá, on the other hand, references the historical and cultural associations of painting in his use of abstraction, a form traditionally associated with Western modernity. His work challenges the viewer’s visions of what he or she considers to be indigenous art, refusing to feed the colonial imaginary and its appetite for exotic representations of the Other. Perhaps the most important thing about Pichillá’s abstraction is how he has developed a language of his own from the perspective of his own subjectivity, allowing himself to be influenced by elements of his environment that are sacred to him, such as the textures of the stones and their veins, which he calls “natural ancestral abstractions”6Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, Remains – Tomorrow. Themes in Contemporary Latin American Abstraction, Hatje Cantz, Berlin, 2022, p. 435. His difference is thus internalized and manifests itself in the creation of his art, impregnating his practice with cultural codes of the ancestral Mayan tradition.

Fig. 5. Antonio Pichilla, Knot, 2016

Fig. 6. Antonio Pichilla, Knot, 2016

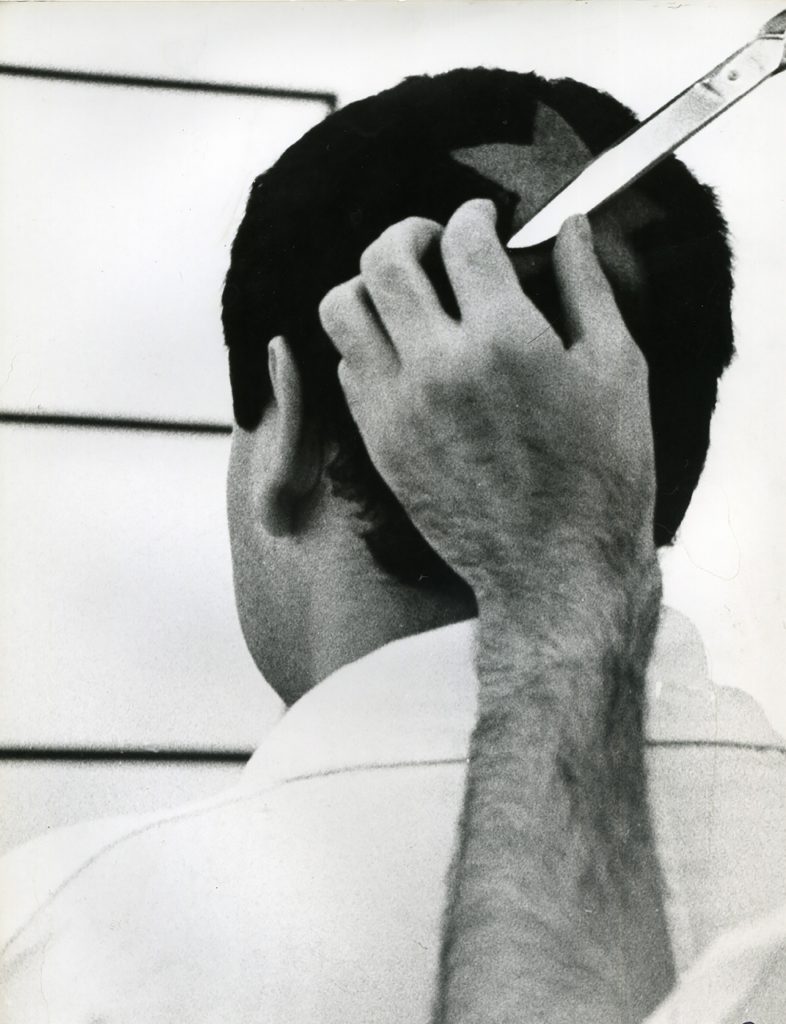

In fourth place we have Carlos Leppe’s performance Acción de la Estrella (1979), in which the artist tonsures a star on his head in a gesture that imitates Marcel Duchamp’s 1919 action. In this performance, Leppe stands behind a transparent structure that simulates the outline of the Chilean flag, turning his head into its solitary star. If many interpret Duchamp’s work in terms of solitude (because of the monk’s tonsure) and fluidity (since the Roman five-pointed star is a sign of femininity), Leppe’s action superimposes these cultural meanings on a political territory. Similarly, Dario Escobar’s work also constitutes an act of Duchampean-influenced superimposition. Drawing Guatemalan flora on a ready-made (a McDonald’s cup), the artist imposes modernity on his local territory.

Fig. 7. Carlos Leppe, Acción de la estrella, 1979

Circulations

Although an important part of the las Yeguas del Apocalipsis’s project was to gain visibility for marginalized communities, Casas and Lemebel doubted the system of legitimization established by art institutions. Mindful that museums are spaces that produce identity and shape our subjectivities in the social sphere, the artists maintained a critical perspective against the normative narratives perpetuated by traditional exhibition formats. Instead of relying on them, las Yeguas chose to infiltrate public spaces in order to avoid the validation system of a museum and its totalizing narratives, intervening spaces such as the headquarters of the Chilean Human Rights Commission in the case of La Conquista de América (1989) or traditional places of learning in the case of Refundación de la Universidad de Chile (1988). In line with these actions, this second section brings together artists who explore through their works the culture and politics of the circulation of visual culture and how these networks produce and reinforce rigid and normative identities.

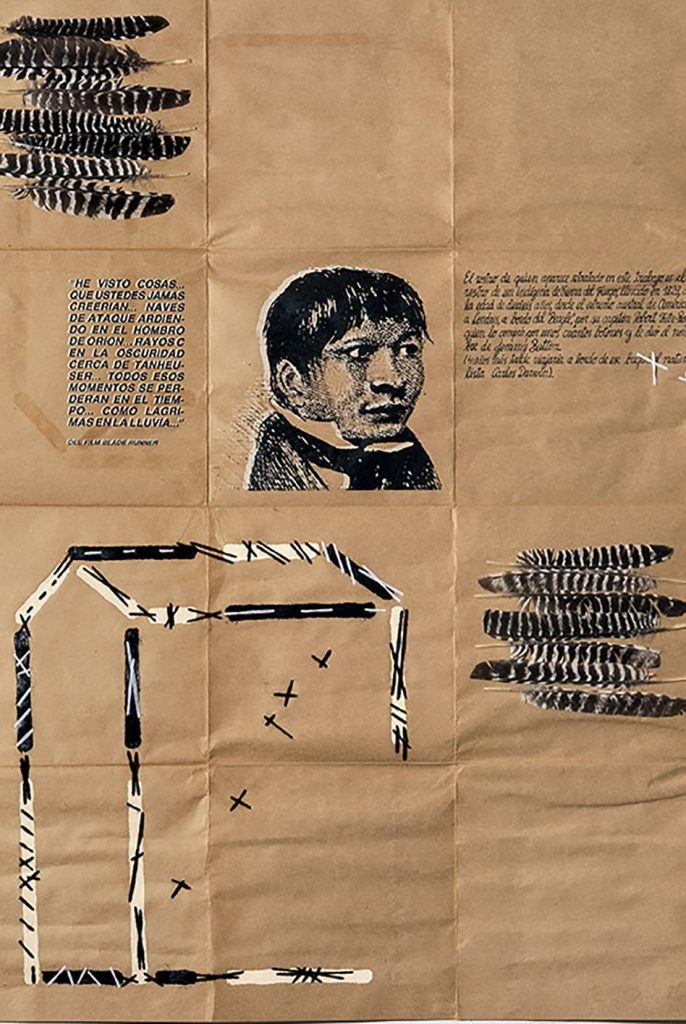

The first of these artists is Eugenio Dittborn, whose aeropostal paintings infiltrate the artistic centers from the remote territory of 1980s Chile. These works can be perceived as the mapping of a complex network of geopolitical relations. In the aeropostal painting Button Plumas (1985), for example, the artist invokes the image of Jemmy Button, a man from Tierra del Fuego who was taken to the United Kingdom and imbued with the customs of that country in order to be supposedly saved from barbarism. In this work, Button symbolizes colonial epistemological violence and is used to explore the confrontation of Western and indigenous cultures, as well as ideas of travel and home. Thus, the theme and format of Dittborn’s work are inseparable: the idea of traveling to a ‘civilized’ center and then returning to Chile resembles the journey that his aeropostal paintings also made. On the other hand, these works also show traces of movement in the folds of the paper that allowed them to be moved, or in the stamps on the envelopes displayed next to them. In this way, the continuous state of transit of the aeropostal paintings is as important as their points of origin and destination: they take from the places where they go but never stay there for long. Hanging directly on the wall, Button Plumas becomes part of the architecture of the gallery, undergoing a “continuous metamorphosis of character that undoes identity”7Willy Thayer, “Eugenio Dittborn: No Man’s Land Paintings”, in Afterall, Vol. 29, 2012, p. 84.

Fig. 8. Eugenio Dittborn, Button Plumas, 1985

Claudia Martinez Garay is also interested in the politics that underlie the devices of art circulation and exhibition. From fiction, her work ÑUQA KAUSAKUSAQ QHEPAYKITAPAS / I WILL OUTLIVE YOU (2017) tells in Quechua the story of a man represented in a Moche huaco. The narrative of the story recounts the life of this man from his childhood to his eventual imprisonment, which allows us to draw a parallel between his biography and the story of the journey of the huaco that was stolen from a tomb in northern Peru and eventually found by the artist in the deposit of a European museum. Fiction thus becomes a tool to restore a sense of agency to those whose histories were erased. In other words, it becomes a tool to resist the totalizing narratives imposed by ethnological museums on foreign cultures.

Fig. 9. Claudia Martínez Garay, KAUSAKUSAQ QHEPAYKITAPAS / I WILL OUTLIVE YOU, 2017

Finally, Marilyn Boror and Juan Pablo Langlois examine the circulation of information through mass media and how it shapes ideas about indigenous identities. In ¡Ni parece Guatemala! (2020), Boror works with the postcard format, historically used to disseminate exoticized images of the colonies. By representing the colonial subject as an object to be observed, the postcard certainly contributed to justify its subjugation. Thus, Boror uses this format to unveil the colonial imaginary, representing the indigenous communities fading away in front of a modern commercial district located in Guatemala City.

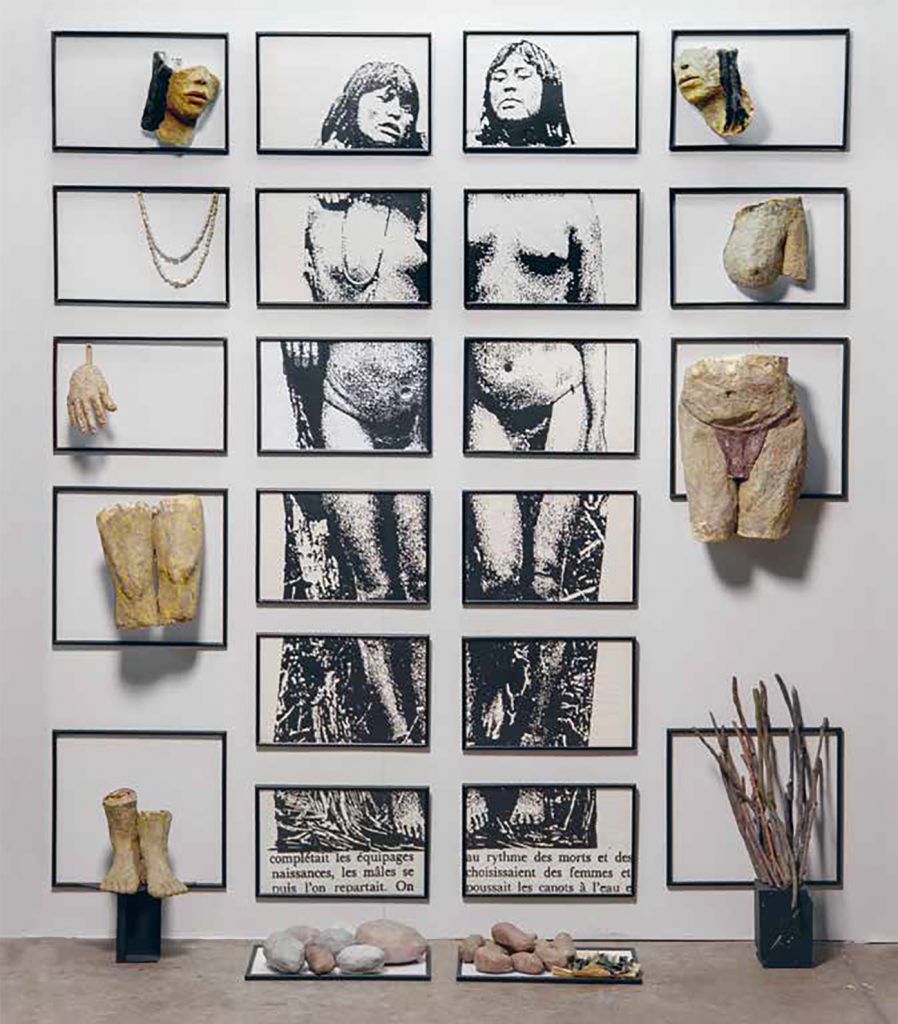

Meanwhile, in Miss Chile, Onas (1990), Juan Pablo Langlois reproduces photographs of indigenous women taken from a book that he found in the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art. By titling his work in this way, the artist refers to the racialized standards of beauty imposed on women through the media. The word miss, on the other hand, also means “to miss”, which, following the logic of Boror’s work, may be another gesture that points to the fading of an identity.

Fig. 10. Juan Pablo Langlois, Miss Chile, Onas, 1990

Body-Territories

In La Conquista de América (1989), las Yeguas del Apocalipsis propose a direct connection between the conquered territory and the body. If the colonial conquest imposed artificial borders on the territory we now know as South America, it also imposed its models of “bourgeois order” on the body, “controlling and stereotyping its excesses”8Eugenia Brito, “Cuestionando lo representable: la fotografía de Paz Errázuriz”, in Nomadías N° 10, 2009, p. 213. From this same perspective, the artists gathered in this third section explore how subjectivity is expressed through the body. If we think of the body as a territory: what happens with those bodies that exceed the frontiers imposed by cultural codes?

In La Manzana de Adán (1981-1989), Paz Errázuriz captures images of gender nonconforming people in the brothels of Chile. The artist, who lived with the subjects of her photographs and formed affective bonds and friendships with them, produces an affective record of dissident bodies that lived in danger for existing outside the binarism and the rigidity of normative identity. Errázuriz’s gaze, on the other hand, is not totalizing, and the artist’s care and attention is present in each image. This allows the people she portrays in this series to maintain their individual personality.

Fig. 11. Paz Errázuriz, La Manzana de Adán, 1981-1989

Still, for Pedro Lemebel, photography as a medium can be problematic for those who do not conform to traditional gender identities: misaligned with the canon of the school photograph, tempted by laughter, by the maladjusted body pose, she is corrected, called to order”9Andrea Giunta, “Sentir, pese a todo”, en Boletín Nº7: Paz Errázuriz, Centro de Estudios de Arte (CEdA), Santiago, 2020, p. 17. Can other modes of representation resist this impulse to order?

A possible answer to this question can be found in Wynnie Mynerva’s wild and messy paintings, which represent the body in a process of constant transformation, in a continuous process of becoming. The refusal of this body to become an object of patriarchal desire is also expressed in its resistance to be visible or to be easily read. In this artist’s paintings, the bodies collide and merge with each other and with the landscape, resist easy identification and often appear genderless. Moreover, from a formal point of view, these paintings exist somewhere between figuration and abstraction, that is, in a liminal space beyond the binarism imposed by Western modernity.

Fig. 12. Wynnie Mynerva, Sin título, 2021

In dialogue with Errázuriz and Mynerva, Amalia Pica’s work reflects on the ways in which we try to understand and make sense of the unknown. Using everyday objects and discarded materials, the artist creates disconcerting assemblages that almost resemble bodies. These compositions, for which we have no words, act as empty vessels that we fill with our own ways of understanding and creating meaning. This reminds us that identity is relational, socially constructed and in a permanent state of flux.

Fig. 13. Amalia Pica, Catachresis #66, 2016

A no man’s land usually denotes the space between two conflicting oppositions. This definition may be an appropriate way to think about some of the works gathered in this exhibition. Indeed, las Yeguas del Apocalipsis and many of the late twentieth-century artists in this exhibition offered their bodies to “create differentiated identities of resistance”10Gerardo Mosquera, “Good‐bye identity, welcome difference. From Latin American art to art from Latin America”, en Third Text Vol. 15, N° 56, 2001, p. 25 , in direct opposition to the dictatorial apparatus’ regulations that aimed to control their dissident subjectivities. In this sense, the word nobody, or no man’s, takes on a political meaning here, referring to those who, for various reasons, have been marginalized

A no man’s land can also be conceived as a middle space, a middle ground with shifting borders in which identity is transformed into something more fluid. It can then be a space in which las Yegua’s body dissolves into an abstraction like that of Antonio Pichilla’s work or in the ineffable constructions of Amalia Pica. Gilles Deleuze, who thought of the concept of identity in terms of territory, argues that we should think of ourselves as grass, whose tangled roots make it impossible to know where it begins or where it ends, and which grows in the spaces in between. In this glassy, borderless map, Lemebel and Casas dance alone but together, in the swaying of a process of constant becoming. From the blood that waters this no man’s land on which they dance, I imagine the grass growing.