I go to the women’s bathroom, but I take my time, wanting to wander a bit first. It’s not that my arrival there was immediate, after all; it took thirty-seven years. Before going in, I pause at an image: the Venus de Milo. But not that Greek marble statue representing a half-bent Aphrodite; rather, the version of her crafted by Lorenza Böttner in 1982, first in Kassel, then in New York, and later in San Francisco. In that performance, Lorenza, then twenty-three, with amputated arms, topless and painted entirely white, stood on a stepped plinth against a black background. Thus, embodying Venus, was the first way I saw her.

In a 1991 documentary, the artist confesses that she wanted to show the beauty of her mutilated body: “I realized how many statues are admired for their beauty despite lacking arms” (Stahlberg, 1991: 14’10”). Trans and amputated, she attempted to remain perfectly still for the duration of the performance, as if she were sculpted from stone. But two things betrayed her: firstly, unlike the Milo statue, Lorenza smiled; and she smiled not only with her mouth but with her eyes as well. Then, her torso. Unlike the flawless, cold torso of the marble Aphrodite, hers didn’t create that unreal impression of smoothness—a quality fit for a goddess. Instead, she was imperfect, human. She breathed.

What stirred within? What was that Venus twisting, besides the representation of classical beauty? Paul Preciado states that Lorenza’s self-portraits and the photographic sequences documenting her transformation process functioned as “performative technologies to create a transgender, armless subjectivity” (Preciado, 2017). But to me—seeing her image just before beginning my own transition, not fully understanding what I was witnessing—there was something emblematic in it. I mean emblematic in the sense of a symbol, a figure conventionally used to symbolically represent an idea or thing.

The more I saw her, the more I understood that Lorenza’s smiling, amputated Venus, with her restless eyes, was, in her apparent stillness, breaking something open. Her image brought forth something else that wasn’t initially there. By defining performance as a “cryptic form of expression” (Stahlberg, 1991: 13’29”), Lorenza opened a possibility for the invisible—a presence building its delay, in that it needed to be summoned. Performance, according to the artist, can initiate “a train of thoughts” that, for me, in the abyss of my prior self, became a vertigo that, for the first time, I felt was loving.

Ángeles Mateo del Pino says Lorenza took a dangerous leap by cross-dressing as a classical figure, “forcing others to dis-identify those gazes that constructed a normative beauty and a deviant one” (Mateo del Pino, 2019: 51). At that crossroads, facing that abyss, Lorenza’s Venus intrigued me, allowed me to move forward, and summoned me to look deeper. Thus, to see myself as trans.

Writer Larissa Pham suggests that the bathroom, with its mirror and private nature, can be a space for rehearsing, self-observation, and preparation before facing the outside world—a place where, despite seeing ourselves, “we can return to being formless” (Pham, 2019). For me as a child, after my mother or father bathed me, within the haziness of steam and fogged-up glass, it was important to regain clarity because, in that safe, floating space of the bathroom, I wasn’t he. I was she.

In his chronicles gathered in Loco Afán (LOM, 1996), Pedro Lemebel refers to Lorenza’s Venus de Milo performance. He says she appears as an amputated whore of the Parthenon. “Something like a topless act in the Acropolis or high heels in Athens, a smuggled guest at the postmodern bacchanal” (Lemebel, 1996: 153). And it’s true; it’s subversive that she is painted white and draped in a toga like a Greek goddess, unsettling the classical canon of beauty with her perfectly amputated body. Her mere existence is destabilizing. But the image works not only as cultural provocation but as a portal. I say that through the rupture of the hegemonic, her smiling, warm, and loving body points to something invisible, something not necessarily there, and in its enigma, it proposes a way forward—a transition. It shows us something we see through her.

The first time I crossed the portal marked for women and entered the women’s bathroom was at night, at a party. Unlike the row of urinals in the men’s bathroom, where one’s gaze is always constrained, directed at a blind spot between tiles (and never at another man), the scene in the women’s bathroom appeared to me multiple, elliptical, and dynamic—like a tornado. I realized that women weren’t afraid to speak or look at each other. They were open to touch, to conversation, to assisting one another. They entered in pairs, separated, regrouped, and in front of the mirror, they fixed their hair, shared makeup, and called each other by name.

The bathroom is where cleansing happens, but also where nothing happens, except looking at oneself. Where one “studies one’s own face,” says Pham, (Pham, 2019). Where it’s possible to recognize oneself in another and another and another. Because in bathrooms and changing rooms, there’s always something that multiplies and something that’s discovered. There’s always something hidden, something kept, and in contrast, something unveiled and shown. I think of the line marked by the Venus’s toga. I think, simply, of the act of undressing before others.

I remember the first time I changed in the women’s changing room after beginning my transition. It was a morning, after a yoga practice. Naturally, I was scared. Naturally, I didn’t want to make anyone uncomfortable. But there was no doubt: I no longer belonged in the men’s changing room. Once I crossed the door to the other bathroom, I quickly disappeared into the choreography of women’s bodies dressing, undressing, raising arms, bending down, showering, and drying their hair. I was curious, and unlike in the men’s bathroom, I didn’t feel the prohibition against holding a gaze or keeping close to those strangers.

The yoga practice had made us all sweat, so many of us were flushed and perspiring. A woman a bit younger and wider than I was, already topless, was trying to remove her shirt, but her soaked skin prevented the synthetic fabric from moving. She was left, arms up and crossed, entirely trapped and blinded by her own clothing. Like a Venus de Milo, but inverted, in that it was the upper part of her body that was wrapped. I watched her turn and turn again, unable to escape her own trap of sweat.

Until an older woman, much thinner, with wrinkled skin and white hair, turned to her. Placing a hand on her shoulder, she stopped her and then, with both hands, helped her undress. When the young woman was finally free of her clothes, she stood nude, facing the older one. She turned, looked her in the eyes, and thanked her. Those two women didn’t know each other, yet one had voluntarily helped the other. Something like that would never have happened in a men’s changing room.

Something like that I had never witnessed before. That blind whirl turned into revelation and relief was a sign—of what happened within the women’s changing room and of my place there. When I averted my gaze, I found myself reflected in the mirror: sweaty and expressionless. The Roman poet Ovid recounted in his Metamorphoses the story of Actaeon and Artemis: Actaeon was a hunter in the woods stalking prey when he stumbled upon the goddess Artemis bathing at the water’s edge. Artemis, accompanied by her nymphs and dismayed by the hunter’s gaze, turned him into a stag. Stripped of his voice, Actaeon couldn’t prevent his bloodthirsty hounds from tearing his body to pieces.

That is, in a few words, also the story of desire and of the gaze. After that first time, the women’s bathroom became, for me, a space where the desiring male gaze seldom reaches and, therefore, cannot exert power over the bodies. A kind of intimate refuge where we, as women, can be sweaty, naked, even uncomfortable. We can ask if we’re okay. Cry, put on makeup, fight, undress.

It was also where my thinking began to crack. Because Actaeon—or the masculine—is not merely a transgression of the gaze but also thought itself, the very thing that, articulated in words, allows us to express and name ourselves.

I read that the Venus de Milo was made in several blocks of marble, but the joints are so perfect that, as a whole, they erase their marks: the joins between them are not visible. That’s why, I think, the cuts on her arms are so noticeable. Her assembly does not admit fractures. And so, when Lorenza embodies that iconic image, she destroys it without touching it. Seeing her for the first time, I felt something breaking—not immediately, but at a distance. A slow twist that, with its strength, set the direction for my transition.

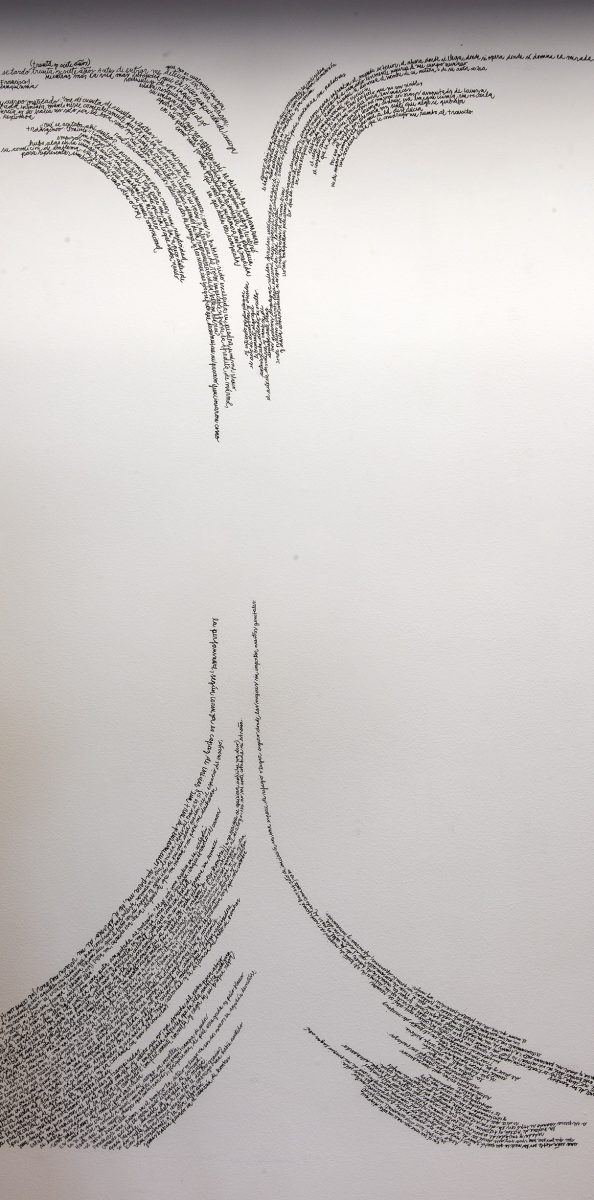

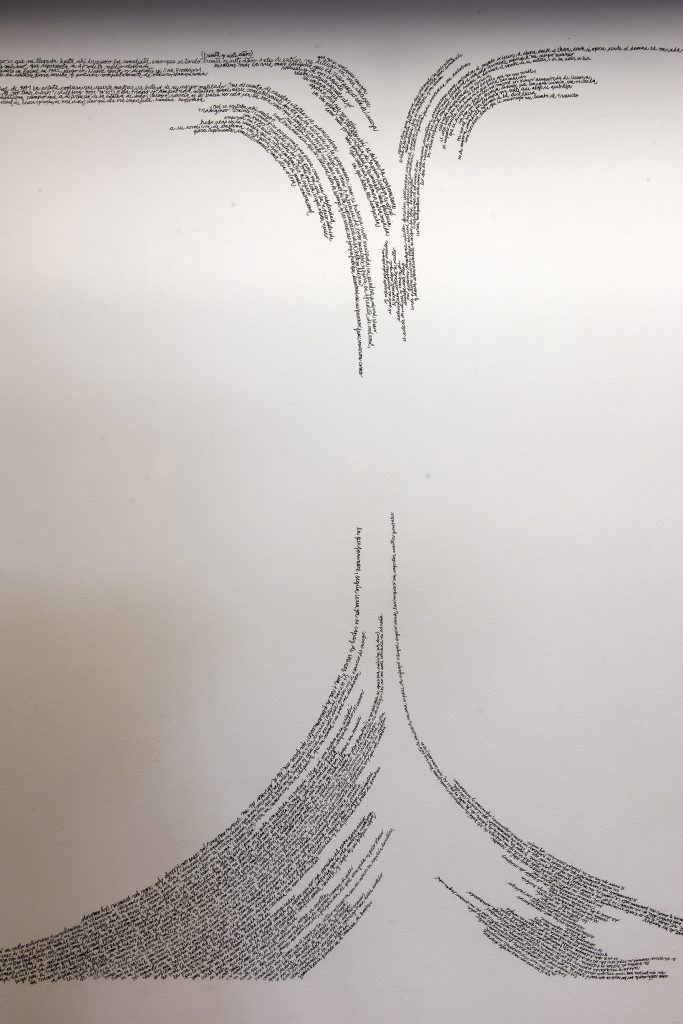

Fig. 1. Ariel Florencia Richards, Venus invertida (“Inverted Venus”), intervention on the wall of the exhibition “My clothes, others’ clothes, many people’s clothes,” presented at Il Posto between March and June 2023.

References

Pham, Larissa (March, 28th 2019). “A Bathroom of One’s Own”. The Paris Review. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/03/28/a-bathroom-of-ones-own/

Stahlberg, Michael (1991). Lorenza. Portrait of an Artist. Docu Short. Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film in Zusammenarbeit mit Seed Pictures, 1991. https:// vimeo.com/29793957. Consulted on January 22 2018.

Lemebel, Pedro (1996). “Lorenza, las alas de la manca”. Loco afán. Crónicas de sidario. Santiago de Chile, LOM, 1996, pp. 151-154.

Mateo del Pino, Ángeles. “Subjetividad transtullida. El cuerpo/corpus de Lorenza Böttner”. Anclajes, vol. XXIII, n.° 3, septiembre-diciembre 2019, pp. 37-57. DOI: 10.19137/anclajes-2019-2334

Preciado, Paul (2017). Lorenza Böttner (1959-1994). Documenta 14. Kassel, Private collection Neue Galerie.. Online edition. http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/21958/lorenza-bottner Consulted on January 22 2018.

_____________ (2018). “Lives and Works of Lorenza Böttner”. South as a State of Mind. Issue #9, documenta 14 #4, Kassel, 2017. Online edition. http://www.documenta14.de/en/south/25298_lives_and_works_of_lorenza_boettner Consulted on January 22 2018.